History of the Universal Monsters!

The Golden Age of the Universal Monster Movie lasts from about 1931 to 1935, but to understand the world into which it was born, allow me first to take you back to the 1920s and the golden age of silents. The 20s really saw the birth of the horror genre in cinema, and it is perhaps appropriate, coming between the two World Wars, that it came from Germany. Robert Wienes The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and F.W. Murnaus Nosferatu (1922) are two of the most significant in the history of the genre, the former with its nightmarish, expressionistic aesthetics and the latter with the original, and best, vampire. The American studio most directly influenced by these was Universal, which was set up in 1915 by Carl Laemmle. Laemmle had opened a Nickelodeon in 1906, and helped bust up the early monopoly of the Motion Pictures Patents Company, thus helping give birth to the studio system that has in some form or another remained in place since. The studio had massive success with versions of Gothic classics like The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925). These starred the Man of A Thousand Faces: Lon Chaney, one of the biggest stars of that decade. With the star system barely in place, he subverted it by being a star not through beauty, but deliberately through its antithesis.  In 1928 Laemmles son, known affectionately simply as Junior, effectively took over from his father. While Laemmle senior had been more ambivalent about the genre, Junior pursued horror further, as America pushed into a new decade, and a new cinema: one that talks. The logical next step was a horror-talkie, and so in 1931 filming began on a version of Dracula. The movie was to star Lon Chaney as the Count (he no doubt would have played it under his trademark heavy make-up), and was to be directed by Tod Browning. Browning had run away to join a circus at the end of the 19th century, a story I repeat simply for its romance and the probable influence it had on his later masterwork, Freaks (1932). But, after just one speaking role, Lon Chaney succumbed to lung cancer, and a mighty void was left at Universal. It was filled, though certainly not immediately, by the actor who had played the role on stage (the movie having been adapted closely from the play, rather than the novel). Although the studio had reservations about him, he had been very successful on stage, genuinely scaring his audiences with his weird delivery and piercing eyes. He was a heavily-accented, suave Hungarian, and his name was Bela Lugosi.

In 1928 Laemmles son, known affectionately simply as Junior, effectively took over from his father. While Laemmle senior had been more ambivalent about the genre, Junior pursued horror further, as America pushed into a new decade, and a new cinema: one that talks. The logical next step was a horror-talkie, and so in 1931 filming began on a version of Dracula. The movie was to star Lon Chaney as the Count (he no doubt would have played it under his trademark heavy make-up), and was to be directed by Tod Browning. Browning had run away to join a circus at the end of the 19th century, a story I repeat simply for its romance and the probable influence it had on his later masterwork, Freaks (1932). But, after just one speaking role, Lon Chaney succumbed to lung cancer, and a mighty void was left at Universal. It was filled, though certainly not immediately, by the actor who had played the role on stage (the movie having been adapted closely from the play, rather than the novel). Although the studio had reservations about him, he had been very successful on stage, genuinely scaring his audiences with his weird delivery and piercing eyes. He was a heavily-accented, suave Hungarian, and his name was Bela Lugosi.  Finally, cinematographer Karl Freund was hired. Freund, a great photographer, had started his career with the German Expressionists (he worked for F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang) and whose career would stretch from these early geniuses to George Cukor, John Huston and Fred Zinnemann. Browning had been friends with Lon Chaney, and they had worked together on MGM. He was disappointed and upset by the loss and, according to some reports, did not really have his heart in Dracula. Whats amazing, then, is how well the movie came out. The success of the picture may be down as much to Freund, who was also an uncredited director for some sequences, and who brings real life to the silent stretches of the film. But no doubt the movies success primarily came down to Lugosi, who with this movie became an instant star.

Finally, cinematographer Karl Freund was hired. Freund, a great photographer, had started his career with the German Expressionists (he worked for F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang) and whose career would stretch from these early geniuses to George Cukor, John Huston and Fred Zinnemann. Browning had been friends with Lon Chaney, and they had worked together on MGM. He was disappointed and upset by the loss and, according to some reports, did not really have his heart in Dracula. Whats amazing, then, is how well the movie came out. The success of the picture may be down as much to Freund, who was also an uncredited director for some sequences, and who brings real life to the silent stretches of the film. But no doubt the movies success primarily came down to Lugosi, who with this movie became an instant star.  It really is an iconic performance, echoing so far into modern culture that most people immediately think of Draculas voice as that of Lugosis even if theyve never seen the movie. Freund lights his eyes in ominous close-ups, and though the movie is completely free of blood and sex, there is an erotic charge to the way he fixes young women in his stare. Watching it now, its a far from perfect movie. After the first act, when the action returns to England, the dialogue scenes become very stagey, betraying the source material. Such sequences are a little tiresome, but the silent scenes, such as Dracula appearing in Minas bedroom, have the power of silent movies. If it werent for Lugosis wonderful voice the movie might have worked just as well as a silent, and many people argue in favour of the simultaneously-filmed Spanish version, which offers you a richer visual experience but no Bela. The original also contains a great performance from Dwight Frye, as the insect-munching Renfield.

It really is an iconic performance, echoing so far into modern culture that most people immediately think of Draculas voice as that of Lugosis even if theyve never seen the movie. Freund lights his eyes in ominous close-ups, and though the movie is completely free of blood and sex, there is an erotic charge to the way he fixes young women in his stare. Watching it now, its a far from perfect movie. After the first act, when the action returns to England, the dialogue scenes become very stagey, betraying the source material. Such sequences are a little tiresome, but the silent scenes, such as Dracula appearing in Minas bedroom, have the power of silent movies. If it werent for Lugosis wonderful voice the movie might have worked just as well as a silent, and many people argue in favour of the simultaneously-filmed Spanish version, which offers you a richer visual experience but no Bela. The original also contains a great performance from Dwight Frye, as the insect-munching Renfield.  Regardless of the flaws, the movie was a hit and work quickly began on a new Monster flick. The studio settled on Mary Shelleys Frankenstein, and Lugosi, whose star was as high as it would ever rise, was lined up for the lead. There are differing reports on this, but it seems French filmmaker Robert Florey was to direct Lugosi as the monster, or he started as the scientist then was shifted to the monster; they were then either fired or quit. At any rate, Florey was replaced by the English James Whale. Whale, whose life is the basis of Bill Condons very good movie Gods And Monsters (1998), had been a successful theatre director. Unusually for the time, he did not conceal his homosexuality, which added to his Englishness may have made him feel doubly like an outsider in Hollywood. He had been a prisoner of war during the First World War, which is where he picked up his interest in drama.

Regardless of the flaws, the movie was a hit and work quickly began on a new Monster flick. The studio settled on Mary Shelleys Frankenstein, and Lugosi, whose star was as high as it would ever rise, was lined up for the lead. There are differing reports on this, but it seems French filmmaker Robert Florey was to direct Lugosi as the monster, or he started as the scientist then was shifted to the monster; they were then either fired or quit. At any rate, Florey was replaced by the English James Whale. Whale, whose life is the basis of Bill Condons very good movie Gods And Monsters (1998), had been a successful theatre director. Unusually for the time, he did not conceal his homosexuality, which added to his Englishness may have made him feel doubly like an outsider in Hollywood. He had been a prisoner of war during the First World War, which is where he picked up his interest in drama.  Whale had worked with Colin Clive both on stage and in his film version of Journeys End (1930) and cast him as the scientist. The casting was perfect: he had just the right balance of mad glint and human empathy for us to feel his passion without being alienated by him. However Whale still had the task of finding someone to replace Lugosi. The oft-told story states that he spotted an imposing figure one day in the Universal canteen, and went over to introduce himself. It was the imposing figure of one William Henry Pratt, better known as Boris Karloff.

Whale had worked with Colin Clive both on stage and in his film version of Journeys End (1930) and cast him as the scientist. The casting was perfect: he had just the right balance of mad glint and human empathy for us to feel his passion without being alienated by him. However Whale still had the task of finding someone to replace Lugosi. The oft-told story states that he spotted an imposing figure one day in the Universal canteen, and went over to introduce himself. It was the imposing figure of one William Henry Pratt, better known as Boris Karloff.  Karloff did not come out of nowhere. Like Lugosi, he had credits throughout the 20s, although they were so poorly paid that he often worked as a labourer between jobs. He had been born in London to Anglo-Indian heritage; his father was a diplomat in the Indian Civil Service. At 11 he moved to Canada and was trying to break into acting within 2 years of that. No one seems quite sure where he got his name from. Karloff and Lugosi are, of course, the two names most people would associate with Universal Horror. They were both immigrants to America, and both brought a level of dignity to the melodrama. Karloff had the ability to lend the horror genre intelligence and humanity. Lugosi, on the other hand, seems to have been let loose from the genre itself, an alien, tormented, occasionally downright insane presence. His performances could be hammy, in the way that later Vincent Price performances would be, but you always felt he was taking everything very seriously, perhaps more seriously than anyone else involved in the movie. He didnt like jokes on set. Eventually he would be buried in his cape. Karloff was a more gentle monster, though appropriately intimidating (Lugosi was a few inches taller than Karloff, but ask anyone and theyll swear it must be the other way around).But his figure and his face were only half-way there, and another important figure entered the Universal Horror Golden Age.

Karloff did not come out of nowhere. Like Lugosi, he had credits throughout the 20s, although they were so poorly paid that he often worked as a labourer between jobs. He had been born in London to Anglo-Indian heritage; his father was a diplomat in the Indian Civil Service. At 11 he moved to Canada and was trying to break into acting within 2 years of that. No one seems quite sure where he got his name from. Karloff and Lugosi are, of course, the two names most people would associate with Universal Horror. They were both immigrants to America, and both brought a level of dignity to the melodrama. Karloff had the ability to lend the horror genre intelligence and humanity. Lugosi, on the other hand, seems to have been let loose from the genre itself, an alien, tormented, occasionally downright insane presence. His performances could be hammy, in the way that later Vincent Price performances would be, but you always felt he was taking everything very seriously, perhaps more seriously than anyone else involved in the movie. He didnt like jokes on set. Eventually he would be buried in his cape. Karloff was a more gentle monster, though appropriately intimidating (Lugosi was a few inches taller than Karloff, but ask anyone and theyll swear it must be the other way around).But his figure and his face were only half-way there, and another important figure entered the Universal Horror Golden Age.  His name was Jack P. Pierce, a make-up artist who had been hired by Laemmle to do Conrad Veidts make-up for The Man Who Laughs (1928). That role, with its permanent grin, was originally going to Chaney, just as the Frankenstein monster would have. But with Chaney gone, both his acting and his innovations with make-up had vanished. Pierce, Whale and, to some degree, Karloff (he suggested the heavy eyelids) created what may be the most famous make-up job in the history of cinema. The monsters flat-head, dead eyes and power terminals (not bolts) are what people think of when they hear Frankenstein. The first image of him is one of the greatest close-ups in cinema.

His name was Jack P. Pierce, a make-up artist who had been hired by Laemmle to do Conrad Veidts make-up for The Man Who Laughs (1928). That role, with its permanent grin, was originally going to Chaney, just as the Frankenstein monster would have. But with Chaney gone, both his acting and his innovations with make-up had vanished. Pierce, Whale and, to some degree, Karloff (he suggested the heavy eyelids) created what may be the most famous make-up job in the history of cinema. The monsters flat-head, dead eyes and power terminals (not bolts) are what people think of when they hear Frankenstein. The first image of him is one of the greatest close-ups in cinema. Both Dracula and Frankenstein rely on very little music; they have some over the credits, and thats it. This was is in the awkward space between the silents and the later, more confident talkies, where trial-and-error had produced a better model for music in talking pictures. Philip Glass has since composed a score for Dracula that works quite well, but I think Frankenstein should be left exactly as it is; rather than date it, the lack of music makes the movie work surprisingly well to modern audiences. Take for instance the great, touching sequence involving the little girl. As soon as we see the monster and the girl together we feel fear, and perhaps notes of hope and sympathy. This scene is followed by the brilliant, jolting shot of the father, walking through the village with his dead child, the town celebrating around him, slowly grinding to a halt as they notice him. Think how far less interesting this sequence might be if the music were telling us exactly how we should be feeling. That scene, and Frankensteins line, now I know what it feels like to be God, ran into troubles with censors and were cut in some States (although cutting from the monster approaching the child to the father with her body resulted in making the sequence more, not less, sinister).

Both Dracula and Frankenstein rely on very little music; they have some over the credits, and thats it. This was is in the awkward space between the silents and the later, more confident talkies, where trial-and-error had produced a better model for music in talking pictures. Philip Glass has since composed a score for Dracula that works quite well, but I think Frankenstein should be left exactly as it is; rather than date it, the lack of music makes the movie work surprisingly well to modern audiences. Take for instance the great, touching sequence involving the little girl. As soon as we see the monster and the girl together we feel fear, and perhaps notes of hope and sympathy. This scene is followed by the brilliant, jolting shot of the father, walking through the village with his dead child, the town celebrating around him, slowly grinding to a halt as they notice him. Think how far less interesting this sequence might be if the music were telling us exactly how we should be feeling. That scene, and Frankensteins line, now I know what it feels like to be God, ran into troubles with censors and were cut in some States (although cutting from the monster approaching the child to the father with her body resulted in making the sequence more, not less, sinister).  This set a precedent, and the increasing pressure over the next decade or so on horror movies was a constant obstacle. But the movie set another precedent: it cost less than $300,000 but took over $5 million in its initial run, dwarfing the success even of Dracula, and in a Depression year at that. Universal had discovered the Jaws of its day, and knew what the audience was craving. Aside from its (massive) historical importance to the genre, it simply stands up as a great movie. Its pacing, photography, and central performances (of Clive and Karloff) are unforgettable. It made the assumption, key to so many movies in the genre, that the real monsters are the humans, and the monster is a victim too (as, to a lesser degree, is Frankenstein). Of all the horror movies made in this time period, this and its sequel are for me the unquestionable masterpieces. The success ensured further additions to the Universal Horror catalogue, starting in 1932 with The Mummy. This time Karl Freund, perhaps in part as thanks for his work in Dracula, was given full directing duties. Karloff was hired once more, and endured some of the least comfortable make-up he was ever subjected to, for the bandaged-up body of Imhotep, regaining life. The effect gives you an idea of his dedication (it was done in one day: the make-up alone took from 11am until 7pm, and two hours to remove after filming); we only actually see him in the full costume very briefly, and for the most part he is seen simply as himself, with some aging make-up applied to his skin here and there. Again Jack Pierce was responsible, although, again, he was not credited; despite the fact he did his most important work there, he didnt get a single credit for a Universal horror movie until The Wolf Man in 1941.

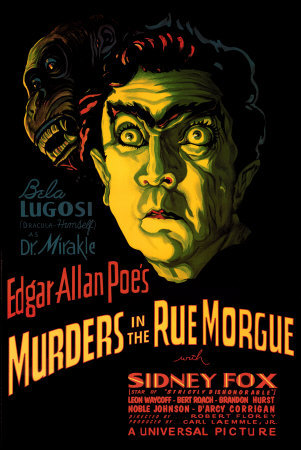

This set a precedent, and the increasing pressure over the next decade or so on horror movies was a constant obstacle. But the movie set another precedent: it cost less than $300,000 but took over $5 million in its initial run, dwarfing the success even of Dracula, and in a Depression year at that. Universal had discovered the Jaws of its day, and knew what the audience was craving. Aside from its (massive) historical importance to the genre, it simply stands up as a great movie. Its pacing, photography, and central performances (of Clive and Karloff) are unforgettable. It made the assumption, key to so many movies in the genre, that the real monsters are the humans, and the monster is a victim too (as, to a lesser degree, is Frankenstein). Of all the horror movies made in this time period, this and its sequel are for me the unquestionable masterpieces. The success ensured further additions to the Universal Horror catalogue, starting in 1932 with The Mummy. This time Karl Freund, perhaps in part as thanks for his work in Dracula, was given full directing duties. Karloff was hired once more, and endured some of the least comfortable make-up he was ever subjected to, for the bandaged-up body of Imhotep, regaining life. The effect gives you an idea of his dedication (it was done in one day: the make-up alone took from 11am until 7pm, and two hours to remove after filming); we only actually see him in the full costume very briefly, and for the most part he is seen simply as himself, with some aging make-up applied to his skin here and there. Again Jack Pierce was responsible, although, again, he was not credited; despite the fact he did his most important work there, he didnt get a single credit for a Universal horror movie until The Wolf Man in 1941.  The cast here also includes Edward Van Sloan, who played Van Helsing in Dracula and variations thereof here and Frankenstein. Indeed the movies use of icons and rebirth make it certainly closer to Dracula than Frankenstein, in quality and style. As with Dracula modern audiences may find it drags in parts, but it is an eerie, handsomely made film and in keeping with the popularity of Egyptian imagery at the time. No other horror movie has ever achieved so many emotional effects by lighting, said Pauline Kael. Universal lost confidence in the way Freund attempted to frighten by tone and mood, rather than shocks, and he never directed another Universal horror. He did however continue to do excellent work as a photographer, and that same year was hired for Murders in the Rue Morgue, a (very) loose adaptation of an Edgar Allan Poe story.

The cast here also includes Edward Van Sloan, who played Van Helsing in Dracula and variations thereof here and Frankenstein. Indeed the movies use of icons and rebirth make it certainly closer to Dracula than Frankenstein, in quality and style. As with Dracula modern audiences may find it drags in parts, but it is an eerie, handsomely made film and in keeping with the popularity of Egyptian imagery at the time. No other horror movie has ever achieved so many emotional effects by lighting, said Pauline Kael. Universal lost confidence in the way Freund attempted to frighten by tone and mood, rather than shocks, and he never directed another Universal horror. He did however continue to do excellent work as a photographer, and that same year was hired for Murders in the Rue Morgue, a (very) loose adaptation of an Edgar Allan Poe story.  It was directed by Robert Florey and starred Bela Lugosi, and was in some way compensation for the two being fired from (or leaving) Frankenstein. It was Lugosis second starring role, here playing a mad scientist who injects women with ape blood, in an attempt to find a mate for his ape. Its not an entirely successful movie, partly because when it was finished Universal cut about 20 minutes, a quarter of the running time, for fear that it was too grizzly. This marked the beginning of Universal Horrors rocky relationship with censors and studio executives. The most contentious indeed were the Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, which generally had little to do with the Poe stories and simply cashed in on his name. The movie showcases some of Freunds best work, and for its faults it is a startling crossover of the sensibilities of American horror with the German Expressionist aesthetic. My favourite shot in the movie is of a girl on a swing, swinging back and forth, the camera swinging with her. This must have been a ridiculously elaborate shot to set up, and the shot has almost zero narrative importance, which is why I love it. It is a flourish, but its also a strangely haunting image. Although Murders in the Rue Morgue was not a hit (and Lugosis contract was not renewed; from then on it would be an uphill struggle to get good roles) there were more of these adaptations. In 1934 they released The Black Cat, starring Karloff and Lugosi (the first time they appeared together in a movie). The studio generally placed Lugosis billing after Karloff, who for this period was credited only by his surname, an indicator of how famous he was.

It was directed by Robert Florey and starred Bela Lugosi, and was in some way compensation for the two being fired from (or leaving) Frankenstein. It was Lugosis second starring role, here playing a mad scientist who injects women with ape blood, in an attempt to find a mate for his ape. Its not an entirely successful movie, partly because when it was finished Universal cut about 20 minutes, a quarter of the running time, for fear that it was too grizzly. This marked the beginning of Universal Horrors rocky relationship with censors and studio executives. The most contentious indeed were the Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, which generally had little to do with the Poe stories and simply cashed in on his name. The movie showcases some of Freunds best work, and for its faults it is a startling crossover of the sensibilities of American horror with the German Expressionist aesthetic. My favourite shot in the movie is of a girl on a swing, swinging back and forth, the camera swinging with her. This must have been a ridiculously elaborate shot to set up, and the shot has almost zero narrative importance, which is why I love it. It is a flourish, but its also a strangely haunting image. Although Murders in the Rue Morgue was not a hit (and Lugosis contract was not renewed; from then on it would be an uphill struggle to get good roles) there were more of these adaptations. In 1934 they released The Black Cat, starring Karloff and Lugosi (the first time they appeared together in a movie). The studio generally placed Lugosis billing after Karloff, who for this period was credited only by his surname, an indicator of how famous he was.  It was directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, an assistant director for F.W. Murnau in the 1920s and most famous now as the director of Detour (1945). Ulmer (for presumably it was he) brought some interesting stylistic touches, particularly in the use of music. While the earlier pictures are almost entirely music-free, The Black Cat, rather experimentally, had a background score that, as in the days of silents, runs throughout the movie. It was an important step in the evolution of music in the movies, although its also very dated and melodramatic, and sounds too much like a silent score for a talkie picture. The movie, with its plot of Satanism and revenge, startled the studio and they insisted on reshoots. Ulmer, however, used the opportunity to shoot an extra sequence, featuring women embalmed in glass cases, offering just the vaguest hint of necrophilia. The movie ends with a famous skinning sequence, although Lugosi by this point was frustrated at being typecast; he was ultimately the storys victim, but ends up just as violently demented as the villain (Karloff). While the producers may have been uneasy about the movie, the public spoke for itself, and The Black Cat was the most successful Universal movie of that year.

It was directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, an assistant director for F.W. Murnau in the 1920s and most famous now as the director of Detour (1945). Ulmer (for presumably it was he) brought some interesting stylistic touches, particularly in the use of music. While the earlier pictures are almost entirely music-free, The Black Cat, rather experimentally, had a background score that, as in the days of silents, runs throughout the movie. It was an important step in the evolution of music in the movies, although its also very dated and melodramatic, and sounds too much like a silent score for a talkie picture. The movie, with its plot of Satanism and revenge, startled the studio and they insisted on reshoots. Ulmer, however, used the opportunity to shoot an extra sequence, featuring women embalmed in glass cases, offering just the vaguest hint of necrophilia. The movie ends with a famous skinning sequence, although Lugosi by this point was frustrated at being typecast; he was ultimately the storys victim, but ends up just as violently demented as the villain (Karloff). While the producers may have been uneasy about the movie, the public spoke for itself, and The Black Cat was the most successful Universal movie of that year.  It may have made Ulmers name, but for an affair with the wife of Carl Laemmles nephew, which promptly had him exiled to B-movie status. The Black Cat was followed by another Poe adaptation, The Raven (1935), which is more of an homage to Poe than anything. Again it features Karloff and Lugosi (credited in that order despite the fact that Lugosi is clearly the star), with Lugosi as an obsessive surgeon with plans to recreate some of the writers nastiest scenes for the family (and fiancé) of the girl he loves. It features a scene with a pendulum (though no pit) that long predates the Roger Corman version. Its one of my favourite Lugosi performances; passionate, hammy (in a good way) and intense. It was not the success that The Black Cat had been and was perhaps a little too grizzly for contemporary audiences, and marks the beginning of the decline of that first, brilliant cycle of horror pictures. But before I get there, allow me to backtrack. In the mean time, James Whale had made two post-Frankenstein pictures for the studio that rate as smaller classics: Firstly, The Old Dark House (1932), starring Karloff, Melvyn Douglas, Gloria Stuart (who would one day throw a necklace off a boat for James Cameron), Raymond Massey and, in his first Hollywood role, Charles Laughton. It concerns a group stranded in a storm in a house owned by a very odd family with secrets in the attic. Among Whales amusing touches is an old man being played by an old woman. Secondly, there was The Invisible Man (1933), an adaptation of H.G. Wellss novel . It features some uncanny trick photography and the first American performance from the brilliant Claude Rains, who the audience doesnt see until the last scene, but whose voice and, particularly, laugh brought a menacing glee to the performance.

It may have made Ulmers name, but for an affair with the wife of Carl Laemmles nephew, which promptly had him exiled to B-movie status. The Black Cat was followed by another Poe adaptation, The Raven (1935), which is more of an homage to Poe than anything. Again it features Karloff and Lugosi (credited in that order despite the fact that Lugosi is clearly the star), with Lugosi as an obsessive surgeon with plans to recreate some of the writers nastiest scenes for the family (and fiancé) of the girl he loves. It features a scene with a pendulum (though no pit) that long predates the Roger Corman version. Its one of my favourite Lugosi performances; passionate, hammy (in a good way) and intense. It was not the success that The Black Cat had been and was perhaps a little too grizzly for contemporary audiences, and marks the beginning of the decline of that first, brilliant cycle of horror pictures. But before I get there, allow me to backtrack. In the mean time, James Whale had made two post-Frankenstein pictures for the studio that rate as smaller classics: Firstly, The Old Dark House (1932), starring Karloff, Melvyn Douglas, Gloria Stuart (who would one day throw a necklace off a boat for James Cameron), Raymond Massey and, in his first Hollywood role, Charles Laughton. It concerns a group stranded in a storm in a house owned by a very odd family with secrets in the attic. Among Whales amusing touches is an old man being played by an old woman. Secondly, there was The Invisible Man (1933), an adaptation of H.G. Wellss novel . It features some uncanny trick photography and the first American performance from the brilliant Claude Rains, who the audience doesnt see until the last scene, but whose voice and, particularly, laugh brought a menacing glee to the performance.  In 1935, after many delays, work finally began on shooting a sequel to Whales massively successful Frankenstein. It was the first (and, few would disagree, best) sequel in this run of movies. The script was by John L. Balderston, who had adapted the play version of Dracula and had a hand in writing Frankenstein and The Mummy. His script was reworked by William Hurlbut and true-crime writer Edmund Pearson (IMDb lists, aside from Mary Shelley, eleven writers, although Robert Floreys early script was dismissed completely). Whale was not aiming to top his original, which he did not think he could do, and so instead took a more tongue-in-cheek approach; primarily, he wanted the movie to be fun. Karloff, of course, was kept on for his iconic role, as was Colin Clive, who Whale saved at the last minute when filming Frankenstein (he was to have perished with the monster in the windmill). Mae Clarke was replaced, apparently due to ill health, by Valerie Hobson, a definite improvement. And added to the cast was Ernest Thesiger, who had turned in a scene-stealing performance in The Old Dark House. Here he played Dr. Pretorius, a mad, camp scientist trying to lure Frankenstein back to a world of gods and monsters. Whale also carried over from that movie its deadpan sense of humour. Franz Waxman was hired for the music, and in contrast to the long silences of the first movie, this one has rich, hypnotic music; its probably the best score of any of these movies. Much has been said about the fact that Whale was openly gay and Bride is often referenced in discussions on Queer Cinema. Many who worked on the movie dismiss the claims, and certainly they are probably overstated. However there is a willing outrageousness about the movie, particularly in the way it flirts with blasphemy, which gives it something of a rebel/outsider quality (also indicated by the fact that the monster is even more clearly the one the audience is rooting for this time). Also, and most famously, added to the cast was Elsa Lanchester, playing the dual role of Mary Shelley in the opening prologue (where Shelley and Byron her how the story continues) and the Bride herself. Shes only in the movie for a few minutes in total, but is the face immediately associated with it. Her streaked hair, startled eyes and bird-like head movements are almost as famous as Karloffs make-up, and again Jack Pierce deserves credit.

In 1935, after many delays, work finally began on shooting a sequel to Whales massively successful Frankenstein. It was the first (and, few would disagree, best) sequel in this run of movies. The script was by John L. Balderston, who had adapted the play version of Dracula and had a hand in writing Frankenstein and The Mummy. His script was reworked by William Hurlbut and true-crime writer Edmund Pearson (IMDb lists, aside from Mary Shelley, eleven writers, although Robert Floreys early script was dismissed completely). Whale was not aiming to top his original, which he did not think he could do, and so instead took a more tongue-in-cheek approach; primarily, he wanted the movie to be fun. Karloff, of course, was kept on for his iconic role, as was Colin Clive, who Whale saved at the last minute when filming Frankenstein (he was to have perished with the monster in the windmill). Mae Clarke was replaced, apparently due to ill health, by Valerie Hobson, a definite improvement. And added to the cast was Ernest Thesiger, who had turned in a scene-stealing performance in The Old Dark House. Here he played Dr. Pretorius, a mad, camp scientist trying to lure Frankenstein back to a world of gods and monsters. Whale also carried over from that movie its deadpan sense of humour. Franz Waxman was hired for the music, and in contrast to the long silences of the first movie, this one has rich, hypnotic music; its probably the best score of any of these movies. Much has been said about the fact that Whale was openly gay and Bride is often referenced in discussions on Queer Cinema. Many who worked on the movie dismiss the claims, and certainly they are probably overstated. However there is a willing outrageousness about the movie, particularly in the way it flirts with blasphemy, which gives it something of a rebel/outsider quality (also indicated by the fact that the monster is even more clearly the one the audience is rooting for this time). Also, and most famously, added to the cast was Elsa Lanchester, playing the dual role of Mary Shelley in the opening prologue (where Shelley and Byron her how the story continues) and the Bride herself. Shes only in the movie for a few minutes in total, but is the face immediately associated with it. Her streaked hair, startled eyes and bird-like head movements are almost as famous as Karloffs make-up, and again Jack Pierce deserves credit. Bride of Frankenstein represents the high point in the Universal Horror canon, and is almost certainly still the most entertaining movie they made (or Whale made, or Karloff made). Although it doesnt contain the shocking sadness of the girls death from the first movie, it does contain the funny and touching sequence with the blind man in the hut. Whales affection for Frankensteins creation (or his creation, depending on how you look at it) was never clearer. The movie was well received by critics and the public, and cemented Whales status as perhaps the single greatest creative force in these pictures. It was such a hit that Whale was asked to come back and film Universals next horror-sequel, Draculas Daughter (1936), but Whale had little interest and the script he wanted to use kept getting rejected by the censors. Eventually the directorial reigns were handed to Lambert Hillyer, who the same year made The Invisible Ray, with Karloff and Lugosi, for Universal. Edward Van Sloane reappeared, his character name inexplicably changed to Von Helsing, this time in pursuit of Gloria Holdens vampire, Countess Marya Zaleska. Its not one of the best of this period, but its an interesting watch. Modern audiences respond particularly to the movies homoeroticism and lesbian overtones. Although we like to think these things simply passed over the censors heads, this was not the case, and Joseph Breen was concerned about the movie from the script stage.

Bride of Frankenstein represents the high point in the Universal Horror canon, and is almost certainly still the most entertaining movie they made (or Whale made, or Karloff made). Although it doesnt contain the shocking sadness of the girls death from the first movie, it does contain the funny and touching sequence with the blind man in the hut. Whales affection for Frankensteins creation (or his creation, depending on how you look at it) was never clearer. The movie was well received by critics and the public, and cemented Whales status as perhaps the single greatest creative force in these pictures. It was such a hit that Whale was asked to come back and film Universals next horror-sequel, Draculas Daughter (1936), but Whale had little interest and the script he wanted to use kept getting rejected by the censors. Eventually the directorial reigns were handed to Lambert Hillyer, who the same year made The Invisible Ray, with Karloff and Lugosi, for Universal. Edward Van Sloane reappeared, his character name inexplicably changed to Von Helsing, this time in pursuit of Gloria Holdens vampire, Countess Marya Zaleska. Its not one of the best of this period, but its an interesting watch. Modern audiences respond particularly to the movies homoeroticism and lesbian overtones. Although we like to think these things simply passed over the censors heads, this was not the case, and Joseph Breen was concerned about the movie from the script stage.  Breens response was by now typical; the 1934 Production Code in America was putting greater and greater pressure on horror movies. This coupled with the lack of success of movies like The Raven ended the first, glorious cycle of Universal Horror, and there was none between 1936 and 1939. However, like Frankensteins creature, you cant keep a good monster down, and with another war looming audiences in America had a replenished appetite for horror; double-bills of Dracula and Frankenstein were selling out every night. The audience had given Universal a message, and in 1938 they returned once more to their flagship franchise. By this point Whale had left Universal, and was replaced by Rowland V. Lee, remembered mainly for this movie and Tower of London the same year. Another sad absentee was Colin Clive; though once more he had been saved at the last minute (at the end of Bride), Clive, a chronic alcoholic, died in 1937 at just 37 years old. Rather than recast the role they opted to centre the story on his son, and for the role selected Basil Rathbone. Rathbone had just played Guy of Gisbourne in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and was soon to play Sherlock Holmes in The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939), both definitive versions. Karloff returned one last time to the role that made his name, while Lugosi was added to the cast as Ygor, the demented assistant.

Breens response was by now typical; the 1934 Production Code in America was putting greater and greater pressure on horror movies. This coupled with the lack of success of movies like The Raven ended the first, glorious cycle of Universal Horror, and there was none between 1936 and 1939. However, like Frankensteins creature, you cant keep a good monster down, and with another war looming audiences in America had a replenished appetite for horror; double-bills of Dracula and Frankenstein were selling out every night. The audience had given Universal a message, and in 1938 they returned once more to their flagship franchise. By this point Whale had left Universal, and was replaced by Rowland V. Lee, remembered mainly for this movie and Tower of London the same year. Another sad absentee was Colin Clive; though once more he had been saved at the last minute (at the end of Bride), Clive, a chronic alcoholic, died in 1937 at just 37 years old. Rather than recast the role they opted to centre the story on his son, and for the role selected Basil Rathbone. Rathbone had just played Guy of Gisbourne in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and was soon to play Sherlock Holmes in The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939), both definitive versions. Karloff returned one last time to the role that made his name, while Lugosi was added to the cast as Ygor, the demented assistant.  The movie is not in the same league as the first two, but once you get over that its a very enjoyable picture. A lot of this is down to Lugosi, who does some of his best work here, and forms an interesting relationship with the monster that would be the centre of the next Frankenstein movie. Rathbone and Karloff are also on fine form, and the movie is the last really good movie in the franchise (save for the Abbott and Costello film). Karloff, who worried that his once terrifying monster was turning into a figure of fun, chose to bow out and never appeared as the monster again (though he did appear in House of Frankenstein (1944), as a scientist). Later that year Tower Of London was released. It is an entertaining historical-drama/horror about the rise of Richard III. As well as sharing a director with Son of Frankenstein, it shares its star, Rathbone, who plays Richard. Also appearing are Karloff and, in one of his earliest roles, Vincent Price. Price and Karloff would team up again years later for Roger Corman, who also remade this movie, with Price as Richard. The last movie the studio made that could be considered a classic (again, Abbott and Costello may be the exception), was 1941s The Wolf Man. This was certainly the last of their classic monsters, although it wasnt there first werewolf movie: that would be 1935s Werewolf of London.

The movie is not in the same league as the first two, but once you get over that its a very enjoyable picture. A lot of this is down to Lugosi, who does some of his best work here, and forms an interesting relationship with the monster that would be the centre of the next Frankenstein movie. Rathbone and Karloff are also on fine form, and the movie is the last really good movie in the franchise (save for the Abbott and Costello film). Karloff, who worried that his once terrifying monster was turning into a figure of fun, chose to bow out and never appeared as the monster again (though he did appear in House of Frankenstein (1944), as a scientist). Later that year Tower Of London was released. It is an entertaining historical-drama/horror about the rise of Richard III. As well as sharing a director with Son of Frankenstein, it shares its star, Rathbone, who plays Richard. Also appearing are Karloff and, in one of his earliest roles, Vincent Price. Price and Karloff would team up again years later for Roger Corman, who also remade this movie, with Price as Richard. The last movie the studio made that could be considered a classic (again, Abbott and Costello may be the exception), was 1941s The Wolf Man. This was certainly the last of their classic monsters, although it wasnt there first werewolf movie: that would be 1935s Werewolf of London.  In that movie the central role was played by Henry Hull, who rejected Jack Pierces original make-up design (as he didnt have the patience to wait for it to be applied) in favour of something simpler, with less covering the face. Hull is not a terribly exciting protagonist, and the movie was a flop, but theres certainly an argument in its favour. Some aspects of the story are arguably dealt with better than in the 1941 film, and one transformation scene stands out: the camera tracks past some pillars following Hull, who has more make-up each time he emerges from a pillar. Its a very simple, effective and economic way of doing the transformation. The Wolf Man, directed by George Wagner, is certainly an improvement however, and it is mostly down to a central performance by a familiar name, if not necessarily a familiar face: Lon Chaney, Jr. Chaney would be typecast in the role (he is the only actor to have played the Wolf Man, not including recent pointless remakes), and it is what he is remembered best for. The character works so well not because of the make-up (Pierce got to return to his original werewolf design) but because of Lon Chaneys amusing, vulnerable likeability. As Larry Talbot, he seems like a gentle big guy; his gentleness as a man makes him fiercer as a wolf.

In that movie the central role was played by Henry Hull, who rejected Jack Pierces original make-up design (as he didnt have the patience to wait for it to be applied) in favour of something simpler, with less covering the face. Hull is not a terribly exciting protagonist, and the movie was a flop, but theres certainly an argument in its favour. Some aspects of the story are arguably dealt with better than in the 1941 film, and one transformation scene stands out: the camera tracks past some pillars following Hull, who has more make-up each time he emerges from a pillar. Its a very simple, effective and economic way of doing the transformation. The Wolf Man, directed by George Wagner, is certainly an improvement however, and it is mostly down to a central performance by a familiar name, if not necessarily a familiar face: Lon Chaney, Jr. Chaney would be typecast in the role (he is the only actor to have played the Wolf Man, not including recent pointless remakes), and it is what he is remembered best for. The character works so well not because of the make-up (Pierce got to return to his original werewolf design) but because of Lon Chaneys amusing, vulnerable likeability. As Larry Talbot, he seems like a gentle big guy; his gentleness as a man makes him fiercer as a wolf.  Co-stars include Claude Rains, very good as ever as Talbots father, and Bela Lugosi as a werewolf eager to pass on the curse. To me this and Son of Frankenstein mark a kind of last hurrah for the golden age of Universal Horror. However in terms of these franchises, were not even at the half way point. Having already made two sequels to The Invisible Man (one starring Vincent Price) and one to The Mummy, the studio returned once more in 1942 to Frankenstein. In The Ghost of Frankenstein (so named because he appears in one scene briefly as a ghost, played by an actor resembling neither Clive nor Rathbone) Lugosi returns to the role of Ygor, this time with Lon Chaney, Jr. as the monster. Chaney and Lugosi are both pretty good, the story is just considerably less interesting than the previous movies. Furthermore Cedric Hardwicke is simply very dull compared to the earlier two scientists (Lionel Atwill, Doctor X himself, is better as his unreliable co-worker). This movie also marked the full transition from A-movie to B-movie, and the Universal Horror output in the 1940s was dominated by sequels.

Co-stars include Claude Rains, very good as ever as Talbots father, and Bela Lugosi as a werewolf eager to pass on the curse. To me this and Son of Frankenstein mark a kind of last hurrah for the golden age of Universal Horror. However in terms of these franchises, were not even at the half way point. Having already made two sequels to The Invisible Man (one starring Vincent Price) and one to The Mummy, the studio returned once more in 1942 to Frankenstein. In The Ghost of Frankenstein (so named because he appears in one scene briefly as a ghost, played by an actor resembling neither Clive nor Rathbone) Lugosi returns to the role of Ygor, this time with Lon Chaney, Jr. as the monster. Chaney and Lugosi are both pretty good, the story is just considerably less interesting than the previous movies. Furthermore Cedric Hardwicke is simply very dull compared to the earlier two scientists (Lionel Atwill, Doctor X himself, is better as his unreliable co-worker). This movie also marked the full transition from A-movie to B-movie, and the Universal Horror output in the 1940s was dominated by sequels.  In 1943 they hit on the idea of combining their monsters, and released Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, where Bela finally gets to play the monster, with limited success. These were followed by House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945). Lon Chaney Jr., as well as playing Frankensteins monster, popped up as The Mummy, and as the Count in Son of Dracula (1943). Although some disagree, I think in the latter hes just plain miscast; he didnt have the threat or the voice for Dracula (not that it needed to be Belas, but it did need something else). In 1948 Bud Abbott and Lou Costello spoofed the genre with Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, which may have proved Karloff right (he was offered the role of the monster but turned it down, instead agreeing to help promote the movie). However even though the monsters are now comic, they arent really the butt of the joke, and while it sealed the (coffin) lid on the Universal Monsters to some degree, the monsters themselves are actually played pretty straight, and the humour comes from Lous occasionally hilarious responses. The monsters were Frankensteins monster, the Wolf Man and Dracula (the title is a bit of a misnomer; aside from being about the monster, rather than Frankenstein, Dracula actually plays the bigger part). Glenn Strange, who had played the role in House of Frankenstein, played the monster, while Chaney revised his role as the Wolf Man. Most significantly, Bela Lugosi played Dracula; after the studio failed to renew his contract he did not return for the sequels, so this is the only time other than the 1931 original when Lugosi played the role on screen. He was a great actor, and that he was buried in his cape (he died in 1956, a year after being admitted to hospital for drug abuse) suggests he had accepted the typecasting that had plagued his career. Looking back his treatment at Universal was fairly shocking; in the 1936-39 horror hiatus apparently he struggled to support his family. After Dracula, he never seemed to get the breaks that Karloff got. Yet he took his work very seriously; on Abbott and Costello, he would get extremely frustrated by the jokes they would play on set. When filming Dracula he would continue to stay in costume and in character, occasionally muttering, I am Dracula (is it possible to say that line without doing the voice?). Karloff, on the other hand, continued making genre movies until his death in 1969 with his usual ability to bring dignity even to the trashiest material. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gg5N9FJc__Q The shadow these movies cast is long indeed. Think of all the actors who effectively got their breaks in these movies: aside from the obvious, there was Charles Laughton, Claude Rains, Gloria Stuart and Vincent Price. When their quality was diminishing in the 1940s, RKO started making horror movies and, under producer Val Lewton, produced many classics. Roger Corman made his own Poe movies in the late 50s and 60s, which too generally bear little resemblance to the source material. Hammer Studios in England, inspired by Universal, made their own, bloodier versions of many of these tales. When John Landis made An American Werewolf in London (1981) he was specifically influenced by The Wolf Man, wanting to outdo its tame transformation scenes (and succeeding). The photography, make-up and performances in these movies echo throughout the genre, and the influence of Universal Horror, like Frankensteins monster, lumbers inelegantly and unstoppably into the 21st century.

In 1943 they hit on the idea of combining their monsters, and released Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, where Bela finally gets to play the monster, with limited success. These were followed by House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945). Lon Chaney Jr., as well as playing Frankensteins monster, popped up as The Mummy, and as the Count in Son of Dracula (1943). Although some disagree, I think in the latter hes just plain miscast; he didnt have the threat or the voice for Dracula (not that it needed to be Belas, but it did need something else). In 1948 Bud Abbott and Lou Costello spoofed the genre with Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, which may have proved Karloff right (he was offered the role of the monster but turned it down, instead agreeing to help promote the movie). However even though the monsters are now comic, they arent really the butt of the joke, and while it sealed the (coffin) lid on the Universal Monsters to some degree, the monsters themselves are actually played pretty straight, and the humour comes from Lous occasionally hilarious responses. The monsters were Frankensteins monster, the Wolf Man and Dracula (the title is a bit of a misnomer; aside from being about the monster, rather than Frankenstein, Dracula actually plays the bigger part). Glenn Strange, who had played the role in House of Frankenstein, played the monster, while Chaney revised his role as the Wolf Man. Most significantly, Bela Lugosi played Dracula; after the studio failed to renew his contract he did not return for the sequels, so this is the only time other than the 1931 original when Lugosi played the role on screen. He was a great actor, and that he was buried in his cape (he died in 1956, a year after being admitted to hospital for drug abuse) suggests he had accepted the typecasting that had plagued his career. Looking back his treatment at Universal was fairly shocking; in the 1936-39 horror hiatus apparently he struggled to support his family. After Dracula, he never seemed to get the breaks that Karloff got. Yet he took his work very seriously; on Abbott and Costello, he would get extremely frustrated by the jokes they would play on set. When filming Dracula he would continue to stay in costume and in character, occasionally muttering, I am Dracula (is it possible to say that line without doing the voice?). Karloff, on the other hand, continued making genre movies until his death in 1969 with his usual ability to bring dignity even to the trashiest material. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gg5N9FJc__Q The shadow these movies cast is long indeed. Think of all the actors who effectively got their breaks in these movies: aside from the obvious, there was Charles Laughton, Claude Rains, Gloria Stuart and Vincent Price. When their quality was diminishing in the 1940s, RKO started making horror movies and, under producer Val Lewton, produced many classics. Roger Corman made his own Poe movies in the late 50s and 60s, which too generally bear little resemblance to the source material. Hammer Studios in England, inspired by Universal, made their own, bloodier versions of many of these tales. When John Landis made An American Werewolf in London (1981) he was specifically influenced by The Wolf Man, wanting to outdo its tame transformation scenes (and succeeding). The photography, make-up and performances in these movies echo throughout the genre, and the influence of Universal Horror, like Frankensteins monster, lumbers inelegantly and unstoppably into the 21st century.