Previously I have written about the way in which

modern superhero narratives speak to, reinterpret and re-contextualise ancient mythologies.* I spoke of how The Flash embodies the powers and design of the ancient messenger Mercury; how Wonder Woman was literally sculpted and brought to life by the Gods on the Amazonian Island; and likened Superman to an Olympian Immortal. In every case, these enduring superhero characters operate in much the same way that legendary figures did in the earliest oral histories, offering adaptive, collaborative narrative spaces in which to use mythology to reflect deep human concerns, making manifest the fears and aspirations of our communal psyche. They function as multifaceted ciphers into which we as a culture can pour our expressions and explorations of our communal identity. In such a context the Hulk was not merely a big smash-monster (although that part is certainly fun); he traces his lineage back through modern tales of scientific hubris exposing the beast within (Jekyll and Hyde; Frankenstein), all the way back to epic sagas of how unchecked rage let lose can ravage the world pitilessly, dehumanising even the greatest figures into little more than ghouls (see Achilles in The Iliad). When I spoke then wildly citing the allusions that can be made to classic myth the best analogy that I could offer for Batman was Hamlet. In order to capture my favourite superhero I was compelled to shift from the godly sphere to the quintessentially mortal, referencing perhaps the most human of all men, a character so obsessed with death and morality that faced with the burden of revenging his murdered father he chews himself up in self-loathing, tortured by the thought of becoming the very thing he despises. Both characters, I noted, lose their parents to crime (Hamlet's mother still lives, but has debased herself by remarrying her husband's killer); both are wealthy young men who must put on an act in front of their friends and family to mask their true purpose; both lurk in the shadows of a corrupted society that was once the pride of their family; and both are wholly adverse to killing (although Hamlet eventually decides to give it a go).* Having now soaked in the concluding film in Christopher Nolan's Batman trilogy, The

Dark Knight Rises, I submit that the simile still works (although Hamlet never had to weather the

true suffering of trying to parallel-park a Batmobile), but I have been struck by another, arguably more revealing analogy. Because there is indeed another character from ancient myth that is entirely fitting for Gotham's protector: he is Prometheus. Batman, the ironically titled '

Dark Knight', is in actuality humanity's ultimate deliverer of

light. Please, allow me to tediously pontificate I mean,

explain... Allow me to explain...

The story of Prometheus is one of the foremost creation myths of humankind. Prometheus was a Titan one of the immortal, earlier gods that would go on to be overthrown by the younger Olympians and their charismatic (if sex-crazed) leader Zeus. He is generally regarded as the god who created human beings (fashioning them from clay and giving them life), but is more famously celebrated for his later, rebellious act of delivering mortals from darkness: stealing light back from the gods (after Zeus had thrown one of his signature tantrums and hidden it away) and returning it to humankind. For his crime, Prometheus was chained to a rock where he daily has his liver eaten out by an eagle only to have it grow back again a physical and psychological torture from which he can find no respite. It can be argued that Prometheus is humanity's foremost supporter, and the ancient god most sympathetic to our plight (indeed, his punishment can be said to only further this empathy: he, like each of us, is trapped on a rock subjected to ceaseless mortal pain). Having gifted us with light and intelligence both literal and metaphorical illumination he banished ignorance, allowing humanity to grow beyond the constraints imposed upon them by a cruel universe filled with dispassionate gods. People need not fear anymore, and could potentially become the masters of their own fate.** Since the release of The Dark Knight Rises, I have read a surprising amount of criticism that claims the film does not have a thematic through line, or that labels the narrative as cluttered, sprawling and discordant.*** Some have even unjustly compared the film to The Dark Knight a spectacular sociological debate between order and chaos that spills out into the streets of Gotham with a cacophony of carnage and explosions and found it lacking. In truth, however, the two films cannot be so artlessly compared; and to accuse The Dark Knight Rises of failing to replicate its predecessor's message is to utterly miss the point of the film, and the role it plays in the larger architecture of the trilogy. Fundamentally, it must be noted that despite

appearing to be a story about a rich kid called Bruce Wayne who one day had a very bad night at the opera, Nolan's Batman films have always, at their heart, been focussed upon society, and the way that people respond to fear. All three films are in fact part of a larger dissertation on civilisation's response to terror and terrorism indeed it is no accident that the only villain that recurs in all three movies is Scarecrow, whose primary weapon is dread. Each movie therefore speaks to different moments in the human response to fear, and each develops its themes on a unique scale, and to very different ends. Pairing one against another to posit which was 'better' at making its point implies a stagnation of argument to which, happily, the films never surrender. To be clear: I would never try to argue that on its own merits Rises is as structurally sound, or elegantly crafted as The Dark Knight I'm not sure anyone would. But The Dark Knight was a

question. It laid out a premise, asking whether compromise and deception can ever be a valid (or even short-term satisfying) response to fear. It ended on a mildly hopeful note, but the darkness was clearly closing in; Rises, in contrast, is finally the answer to that original query. The one necessarily compliments and responds to the other; and although it is perhaps not fair that the later film must rely on what preceded it to fully articulate its meaning, this is not a failing of its structure, rather evidence that Nolan had something more expansive and multidimensional in mind. Once again, while the series may at first appear to be about a rich boy, in pain, in a cape, in actuality the series has always been about Gotham, with the city itself as the expression of a human soul in conflict. Nolan taps into a whole history of Greek and Shakespearean drama, where society is a manifestation of the individual (where something is rotten in Denmark; or Scotland plunges into unholy eternal night), and puts the Batman right where he belongs: centre stage. As such, he is here much more of a communal construct, a collaboration, than he appears in other versions of the Batman mythology. Nolan's universe makes it abundantly clear that although Bruce wears the mask, there would be no Batman without Alfred to stitch his wounds, without Lucius Fox to make his gadgets, Commissioner Gordon with whom to collaborate, the Mayor to turn a blind eye, Harvey Dent to advocate, the history and training of the League of Shadows and in this latest film: without Catwoman and a certain new young detective to rely upon. Nolan's vision is about the construction of a symbol, the kind of emblem in which a mass of people need to invest themselves to fight oppression and inspire change.

The whole trilogy is about fear how we as a peoples respond to cultures of fear, how we can strive to confront and not be governed by the faceless terrors that numb our souls to apathy. In many ways a superhero film has been the best (perhaps only) means through which to best explore in fiction our social crisis in the wake of the September 11 attacks and the subsequent 'War on Terror', providing an often uncompromising space in which to play out our negotiation of idealism and concessions of freedom for security. In Batman Begins Gotham is on the verge of tearing itself apart through a slow surrender to dread. While condemning the city to be purged with fire, Ra's al Ghul declares it a society that has degenerated into crime and inequity because it allowed itself to be terrorised by the will of the unjust. Good people have failed to stand up for what they believe, and fear has corrupted the very soul of the state a decay that is exacerbated and literalised at the end of the narrative when a nerve gas leads everyone to descend into paranoia and violence. Bruce Wayne, his own parents victims, therefore creates Batman as the answer to this demoralising fugue state, believing (while striving to maintain a moral code), that he can bring fear to those who would prey upon the fears of others. In his vigilante crusade he strives to show that criminals have reason to be scared when people refuse to be cowed. The second film however is a mediation upon the compromises that are made in the face of fear: those lines that we are willing to cross in pursuit of safety and order. The Joker, a creature of anarchic devastation tears through the city, seemingly unmotivated. He is terrorism personified: beyond reason and seeking to tear down civility by any means necessary. By the end of the film, in response to this chaos, there is no one who has not compromised themselves and their ethics: Gordon is willing to perpetuate a terrible lie for a greater good; Lucius agrees to see his technology turned into a violation of basic freedoms; Alfred burns the letter from Rachael, concealing a truth that he feels would be too painful for Bruce to know; and Harvey Dent (the bipolar face at the heart of the narrative) has his own

very bad day... No one gets through that film both alive and unscarred by the events that they have survived. The Joker measures the human spirit with pressure, and although ultimately, it does not break it is damaged, perhaps irreparably by the experience. More than any other character, Batman, over the course of The Dark Knight,

uses several morally and legally objectionable techniques to combat crime and terrorism he performs an act of extraordinary rendition; he savagely interrogates a prisoner;

he constructs an elaborate bat sonar that invades to privacy of every citizen in a free state. He takes extreme measures, using tools of deceit that violate basic freedoms in order to protect the lives of his fellow citizens, but in the end it is not his amoral allowances that save Gotham, it is Gotham's spirit itself. When the Joker devises a moral power play in which two boats are tasked with killing others before killing themselves, neither side proves capable of making that final selfish choice to take another's life before their own. The Joker, despite being an astute observer of human behaviour, had misjudged the very fundamental good at the heart of humanity. We value the life of others, and in doing so validate the worth of our own. At the end of The Dark Knight

Batman has not yet learned the lesson of his trilogy yet, and so takes upon himself a new lie, deciding to accept the blame for the death of Harvey Dent. In order to give the world a white knight to idolise and emulate, he provide an appealing lie around which Gotham could build a corrosive fiction: Batman is a villain; Harvey Dent was an uncorrupted victim and champion for good. In an effort to protect and inspire the good in others, Batman had compromised himself and sacrificed the very freedoms he would seek to cherish and at the beginning of The Dark Knight Rises we see where this deceit has led the city, and Bruce Wayne himself... Hence why Batman now has a limp.

Indeed, everyone starts the concluding chapter still nursing the metaphorical and literal wounds of the previous film: Jim Gordon is a weathered shell of a man, weighed down by the enormity of the lie he has perpetuated in the city's idolatry of Harvey Dent; Alfred lives with the sorrow of seeing the child left in his care now a sallow hermit wallowing in grief and self-loathing; even Lucius Fox sits chafing in a boardroom, stunted from growing the company he stewards and itching to unleash a batch of new toys with comical 'Bat' prefixes. And Bruce Wayne, physically worn down and spiritual sapped, a Spruce Goose blueprint away from total breakdown, awaits the excuse to suit up again and end his suffering via street-punk assisted suicide. Fear has pressed in on each of these people; it has led them to compromise themselves; led them to fabricate lies; to hide beneath falsehoods in the service of a 'greater good'. And so, in contrast, this final act in the trilogy is about finding a way, at last, to genuinely ascend beyond the governance and definition of fear. Indeed, this theme of ascension is built into every aspect of the text: in Bruce Wayne's climb from prison; in Batman's rise from being broken and left for dead; from the rise of the citizenry (both in the wake of Bane's fabricated social inequity, to their subsequent

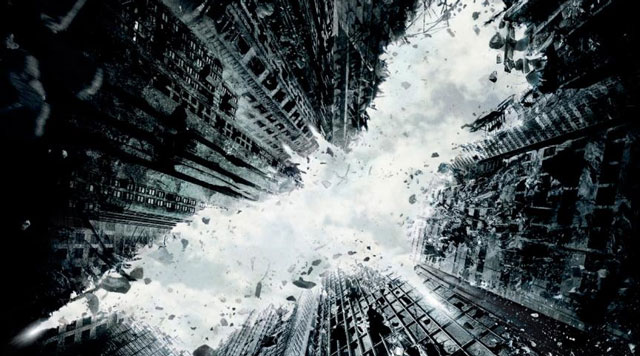

genuine pursuit for justice); to the restoration of the police officers who crawl back into the light to restore order; from Selina Kyle striving to escape the limitations of her identity, finally inspired to stand for something more than herself; to John Blake stepping onto a platform that lifts him toward a whole new path in life... The film therefore concerns itself with exploring the way in which society can transcend intractable cycles of behaviour, how it can confront truth and ascend beyond the stifling limitations of moral concession. The opening shot of the film is a Batman symbol being formed in cracking ice, and it's the perfect metaphor for this narrative: the glacial stress of all this injustice in the name of order, all this compromise to terror in the name of peace, has been building for some time, and the events of this movie are its final cathartic eruption. Society will be changed, people die, but they will die knowing that they fought for what was right, not bowed down or compromised, finally not permitting themselves to be dictated to by fear.

Foremost, as the narrative reveals, division and demonization does not offer an answer to the threat of injustice. Some have argued that the 'uprising' depicted in the film concerns class injustice (a number of reviewers have accused Nolan of making some definitive statement on the Occupy Wall Street movement), but it should be remembered that the instigator, Bane, is not at all concerned with the issues of the 'rich' versus 'poor'. Indeed, he'd be fine if the conflict tearing at Gotham's citizens was My Little Ponies versus Transformers. All Bane seeks to do is sew social division through the demonization of the

other, whatever that other may be. It is a tactic of partition in which terror and suspicion allow morality to be negated in yet another toxically flawed pursuit of 'justice' another cycle of fear-mongering that leads to only more recrimination and amorality. It is only by wholly dissolving such falsehoods, the narrative reveals, that there can be any hope for healing a fractured society. As Alfred states at a pivotal moment in Bruce's journey: it is now time for the truth to have its day, to trust that as a society we are all adult enough to deal with it.**** And that's why in this film we no longer only see Batman in the shadows. By the end he's standing in broad daylight, no longer just a redirected piece of the dark a product of fear used to terrify the fearsome he is now a symbol of so much more. He is resilience; sacrifice; a belief in a cause greater than oneself that can only be achieved by remaining just, and not weaponising deceit for the 'greater good'. In this context it is clear that everything spoken of as 'supporting' rendition, covert spying, and media control in The Dark Knight was merely setting the stage for this, the actual message of these films. Batman, manifestation of our culture's soul, was driven to his breaking point

was almost broken but in clawing his way back from it, by not tipping over into absolute compromise, he is able to reassert himself, to stand for something more. Nolan therefore finds a way to end the Batman mythos, while keeping its spirit alive. The Bruce Wayne Batman 'dies' sacrificing himself for the city, taking upon himself the devastation that such recrimination and division has wrought but in that act of sacrifice he inspires others. Thus Batman the

myth does not die, instead he erupts in a messianic dispersal. More than just a man in a suit, he reveals himself to be an idea, a symbol, one that in its cultural diffusion has more power, more influence, than a single man with a grapple gun and pointy ears ever could. The symbolism of light throughout the work, climbing out of darkness, longingly yearning to ascend, both culturally and personally, from a state of mire and oppression to an illuminated burst of freedom, is one potently literalised with a ball of white igniting the horizon. Batman reveals himself to be Prometheus: he snatches the light from the seemingly all-powerful and distributes it to the frightened masses cowering in fear.

Batman, throughout the three films but most particularly in this final statement of purpose is a construct, the collaboration of a community (from the physical man in Bruce; to the funds from his family; to the partnership with the police force in Gordon; the collaboration with the DA in Dent; the gadgets from Lucius Fox; the medical treatment from Alfred; the mask identity perpetuated by Alfred; the strategising of purchases from Alfred; the sandwiches Alfred makes; Alfred's building a freaking

Batcave ...um, Alfred is kind of important). Anyhoo: Batman here is a pastiche figure, one that, although tethered to the body of one man, could not operate without the support structure of many. So blowing him up annihilating the individual to bring salvation to the many literally disperses him back amongst the populace that brought him into being. Batman, in an act of destruction, is ironically only then truly created: now no longer localised around one perishable man and a bunker of gadgets, but ascending to the role of a guiding aspiration. Postmodern Prometheus, with that final illuminatory burst he transcends the status of urban legend and becomes an ideological compass, now so engrained in the minds of the people, so central to their faith in themselves, that he comes to be immortalised in statue form. He stands at the heart of their city, representative of a newly restored longing to fight oppression, to remind the populace they no longer need be bowed by fear; that in their unity, and their belief in justice, such measures need never be necessary again. It may, of course, seem peculiar that at the end Gotham has been left almost a wasteland an entire devastated infrastructure, criminals wandering the street, while erstwhile protector Bruce Wayne appears to be laughing it up, sipping espressos in the European sun with a pretty lady. But rather than abandoning his post, he knows finally that he has given everything that he can to that role. The Batman has ascended beyond him, and the best thing that he can do, finally, is to embrace that newfound life that Selina, and Alfred's long-held wish for peace, now offer him. Wayne originally became Batman, he tells Blake, because he wanted to be a symbol, a symbol to frighten those who would bring fear to others. Criminals would not know who or where he was:

Batman would be real: he would be out there; and he could be anyone. But the series reveals that this kind of vigilantism is short term. Fear fighting fear; terror begetting only more (if displaced) terror: it is in such a landscape that creatures like the Joker prosper, an entity vomited up from the darkest recesses of the human psyche, to shake the cages of the rational world and expose the noxious raging id beneath the demure surface of the superego. Ultimately, order cannot not be imposed upon chaos through deception, by using the tools of terror to combat terrorism.

Batman may have begun as a tool to redirect horror, but the concluding film shows that Batman's ultimate purpose was to reveal to us how to dissolve fear itself. The only way in which to combat terror, to overcome dread, is to bring it into the light. As Alfred says, pleading for Wayne not to waste himself in an act of meaningless self-immolation: 'I am using the truth, Master Wayne. Maybe it's time we all stop trying to outsmart the truth and let it have its day.' And in coming into the light, stepping out of the shadows in order to sacrifice himself to something greater, Batman does indeed become a true symbol:

Batman is real: he is in here; and he is everyone. No longer would people live under the yoke of lies to numb themselves from responsibility. Batman is in all of us, an ideal, a truth to be cherished, and a heroism we all can all aspire to uphold. Batman, Postmodern Prometheus, sinks himself into shadow in order to ultimately deliver us light. And that is why Bruce Wayne could not die. Death would be too easy; death would be yet another slide into an easy fix; a surrender to the nihilistic self-destructive impulse that his grief had driven him toward. The harder thing, he comes to see,

is living: fighting each day to stand for something, to prosper and do good. By finally embracing his place alongside his fellow humanity, Bruce finds the strength to do the most remarkable thing of all: to believe in life itself. And besides, in some versions of the ancient myth, even Prometheus gets untied from the rock. *

http://whatculture.com/comics/batman-the-new-gods-of-the-super-heroic.php ** In Greek Prometheus' name translates as 'fore thinker'; he is a character who uses his brains to plan out his actions. Batman is known for his physical resilience and strength, sure, but he is foremost the Greatest Detective. It is his mind that sets him apart from the other heroes, and his subversive cunning that proves his most valuable tool. *** One analysis in particular by Film Crit Hulk (who writes under the gimmick of typing in all caps), offers a rather mystifying reading of the narrative in which he dismisses the film as 'cynical', accusing it of having no narrative cohesion whatsoever. He does, however, base much of this upon his utterly subjective speculation about what he thinks Nolan

might have done with the story

had Heath Ledger lived. **** A moment in which Michael Caine is acting his heart out. I salute you, sir.

Previously I have written about the way in which modern superhero narratives speak to, reinterpret and re-contextualise ancient mythologies.* I spoke of how The Flash embodies the powers and design of the ancient messenger Mercury; how Wonder Woman was literally sculpted and brought to life by the Gods on the Amazonian Island; and likened Superman to an Olympian Immortal. In every case, these enduring superhero characters operate in much the same way that legendary figures did in the earliest oral histories, offering adaptive, collaborative narrative spaces in which to use mythology to reflect deep human concerns, making manifest the fears and aspirations of our communal psyche. They function as multifaceted ciphers into which we as a culture can pour our expressions and explorations of our communal identity. In such a context the Hulk was not merely a big smash-monster (although that part is certainly fun); he traces his lineage back through modern tales of scientific hubris exposing the beast within (Jekyll and Hyde; Frankenstein), all the way back to epic sagas of how unchecked rage let lose can ravage the world pitilessly, dehumanising even the greatest figures into little more than ghouls (see Achilles in The Iliad). When I spoke then wildly citing the allusions that can be made to classic myth the best analogy that I could offer for Batman was Hamlet. In order to capture my favourite superhero I was compelled to shift from the godly sphere to the quintessentially mortal, referencing perhaps the most human of all men, a character so obsessed with death and morality that faced with the burden of revenging his murdered father he chews himself up in self-loathing, tortured by the thought of becoming the very thing he despises. Both characters, I noted, lose their parents to crime (Hamlet's mother still lives, but has debased herself by remarrying her husband's killer); both are wealthy young men who must put on an act in front of their friends and family to mask their true purpose; both lurk in the shadows of a corrupted society that was once the pride of their family; and both are wholly adverse to killing (although Hamlet eventually decides to give it a go).* Having now soaked in the concluding film in Christopher Nolan's Batman trilogy, TheDark Knight Rises, I submit that the simile still works (although Hamlet never had to weather the true suffering of trying to parallel-park a Batmobile), but I have been struck by another, arguably more revealing analogy. Because there is indeed another character from ancient myth that is entirely fitting for Gotham's protector: he is Prometheus. Batman, the ironically titled 'Dark Knight', is in actuality humanity's ultimate deliverer of light. Please, allow me to tediously pontificate I mean, explain... Allow me to explain...

Previously I have written about the way in which modern superhero narratives speak to, reinterpret and re-contextualise ancient mythologies.* I spoke of how The Flash embodies the powers and design of the ancient messenger Mercury; how Wonder Woman was literally sculpted and brought to life by the Gods on the Amazonian Island; and likened Superman to an Olympian Immortal. In every case, these enduring superhero characters operate in much the same way that legendary figures did in the earliest oral histories, offering adaptive, collaborative narrative spaces in which to use mythology to reflect deep human concerns, making manifest the fears and aspirations of our communal psyche. They function as multifaceted ciphers into which we as a culture can pour our expressions and explorations of our communal identity. In such a context the Hulk was not merely a big smash-monster (although that part is certainly fun); he traces his lineage back through modern tales of scientific hubris exposing the beast within (Jekyll and Hyde; Frankenstein), all the way back to epic sagas of how unchecked rage let lose can ravage the world pitilessly, dehumanising even the greatest figures into little more than ghouls (see Achilles in The Iliad). When I spoke then wildly citing the allusions that can be made to classic myth the best analogy that I could offer for Batman was Hamlet. In order to capture my favourite superhero I was compelled to shift from the godly sphere to the quintessentially mortal, referencing perhaps the most human of all men, a character so obsessed with death and morality that faced with the burden of revenging his murdered father he chews himself up in self-loathing, tortured by the thought of becoming the very thing he despises. Both characters, I noted, lose their parents to crime (Hamlet's mother still lives, but has debased herself by remarrying her husband's killer); both are wealthy young men who must put on an act in front of their friends and family to mask their true purpose; both lurk in the shadows of a corrupted society that was once the pride of their family; and both are wholly adverse to killing (although Hamlet eventually decides to give it a go).* Having now soaked in the concluding film in Christopher Nolan's Batman trilogy, TheDark Knight Rises, I submit that the simile still works (although Hamlet never had to weather the true suffering of trying to parallel-park a Batmobile), but I have been struck by another, arguably more revealing analogy. Because there is indeed another character from ancient myth that is entirely fitting for Gotham's protector: he is Prometheus. Batman, the ironically titled 'Dark Knight', is in actuality humanity's ultimate deliverer of light. Please, allow me to tediously pontificate I mean, explain... Allow me to explain...  The story of Prometheus is one of the foremost creation myths of humankind. Prometheus was a Titan one of the immortal, earlier gods that would go on to be overthrown by the younger Olympians and their charismatic (if sex-crazed) leader Zeus. He is generally regarded as the god who created human beings (fashioning them from clay and giving them life), but is more famously celebrated for his later, rebellious act of delivering mortals from darkness: stealing light back from the gods (after Zeus had thrown one of his signature tantrums and hidden it away) and returning it to humankind. For his crime, Prometheus was chained to a rock where he daily has his liver eaten out by an eagle only to have it grow back again a physical and psychological torture from which he can find no respite. It can be argued that Prometheus is humanity's foremost supporter, and the ancient god most sympathetic to our plight (indeed, his punishment can be said to only further this empathy: he, like each of us, is trapped on a rock subjected to ceaseless mortal pain). Having gifted us with light and intelligence both literal and metaphorical illumination he banished ignorance, allowing humanity to grow beyond the constraints imposed upon them by a cruel universe filled with dispassionate gods. People need not fear anymore, and could potentially become the masters of their own fate.** Since the release of The Dark Knight Rises, I have read a surprising amount of criticism that claims the film does not have a thematic through line, or that labels the narrative as cluttered, sprawling and discordant.*** Some have even unjustly compared the film to The Dark Knight a spectacular sociological debate between order and chaos that spills out into the streets of Gotham with a cacophony of carnage and explosions and found it lacking. In truth, however, the two films cannot be so artlessly compared; and to accuse The Dark Knight Rises of failing to replicate its predecessor's message is to utterly miss the point of the film, and the role it plays in the larger architecture of the trilogy. Fundamentally, it must be noted that despite appearing to be a story about a rich kid called Bruce Wayne who one day had a very bad night at the opera, Nolan's Batman films have always, at their heart, been focussed upon society, and the way that people respond to fear. All three films are in fact part of a larger dissertation on civilisation's response to terror and terrorism indeed it is no accident that the only villain that recurs in all three movies is Scarecrow, whose primary weapon is dread. Each movie therefore speaks to different moments in the human response to fear, and each develops its themes on a unique scale, and to very different ends. Pairing one against another to posit which was 'better' at making its point implies a stagnation of argument to which, happily, the films never surrender. To be clear: I would never try to argue that on its own merits Rises is as structurally sound, or elegantly crafted as The Dark Knight I'm not sure anyone would. But The Dark Knight was a question. It laid out a premise, asking whether compromise and deception can ever be a valid (or even short-term satisfying) response to fear. It ended on a mildly hopeful note, but the darkness was clearly closing in; Rises, in contrast, is finally the answer to that original query. The one necessarily compliments and responds to the other; and although it is perhaps not fair that the later film must rely on what preceded it to fully articulate its meaning, this is not a failing of its structure, rather evidence that Nolan had something more expansive and multidimensional in mind. Once again, while the series may at first appear to be about a rich boy, in pain, in a cape, in actuality the series has always been about Gotham, with the city itself as the expression of a human soul in conflict. Nolan taps into a whole history of Greek and Shakespearean drama, where society is a manifestation of the individual (where something is rotten in Denmark; or Scotland plunges into unholy eternal night), and puts the Batman right where he belongs: centre stage. As such, he is here much more of a communal construct, a collaboration, than he appears in other versions of the Batman mythology. Nolan's universe makes it abundantly clear that although Bruce wears the mask, there would be no Batman without Alfred to stitch his wounds, without Lucius Fox to make his gadgets, Commissioner Gordon with whom to collaborate, the Mayor to turn a blind eye, Harvey Dent to advocate, the history and training of the League of Shadows and in this latest film: without Catwoman and a certain new young detective to rely upon. Nolan's vision is about the construction of a symbol, the kind of emblem in which a mass of people need to invest themselves to fight oppression and inspire change.

The story of Prometheus is one of the foremost creation myths of humankind. Prometheus was a Titan one of the immortal, earlier gods that would go on to be overthrown by the younger Olympians and their charismatic (if sex-crazed) leader Zeus. He is generally regarded as the god who created human beings (fashioning them from clay and giving them life), but is more famously celebrated for his later, rebellious act of delivering mortals from darkness: stealing light back from the gods (after Zeus had thrown one of his signature tantrums and hidden it away) and returning it to humankind. For his crime, Prometheus was chained to a rock where he daily has his liver eaten out by an eagle only to have it grow back again a physical and psychological torture from which he can find no respite. It can be argued that Prometheus is humanity's foremost supporter, and the ancient god most sympathetic to our plight (indeed, his punishment can be said to only further this empathy: he, like each of us, is trapped on a rock subjected to ceaseless mortal pain). Having gifted us with light and intelligence both literal and metaphorical illumination he banished ignorance, allowing humanity to grow beyond the constraints imposed upon them by a cruel universe filled with dispassionate gods. People need not fear anymore, and could potentially become the masters of their own fate.** Since the release of The Dark Knight Rises, I have read a surprising amount of criticism that claims the film does not have a thematic through line, or that labels the narrative as cluttered, sprawling and discordant.*** Some have even unjustly compared the film to The Dark Knight a spectacular sociological debate between order and chaos that spills out into the streets of Gotham with a cacophony of carnage and explosions and found it lacking. In truth, however, the two films cannot be so artlessly compared; and to accuse The Dark Knight Rises of failing to replicate its predecessor's message is to utterly miss the point of the film, and the role it plays in the larger architecture of the trilogy. Fundamentally, it must be noted that despite appearing to be a story about a rich kid called Bruce Wayne who one day had a very bad night at the opera, Nolan's Batman films have always, at their heart, been focussed upon society, and the way that people respond to fear. All three films are in fact part of a larger dissertation on civilisation's response to terror and terrorism indeed it is no accident that the only villain that recurs in all three movies is Scarecrow, whose primary weapon is dread. Each movie therefore speaks to different moments in the human response to fear, and each develops its themes on a unique scale, and to very different ends. Pairing one against another to posit which was 'better' at making its point implies a stagnation of argument to which, happily, the films never surrender. To be clear: I would never try to argue that on its own merits Rises is as structurally sound, or elegantly crafted as The Dark Knight I'm not sure anyone would. But The Dark Knight was a question. It laid out a premise, asking whether compromise and deception can ever be a valid (or even short-term satisfying) response to fear. It ended on a mildly hopeful note, but the darkness was clearly closing in; Rises, in contrast, is finally the answer to that original query. The one necessarily compliments and responds to the other; and although it is perhaps not fair that the later film must rely on what preceded it to fully articulate its meaning, this is not a failing of its structure, rather evidence that Nolan had something more expansive and multidimensional in mind. Once again, while the series may at first appear to be about a rich boy, in pain, in a cape, in actuality the series has always been about Gotham, with the city itself as the expression of a human soul in conflict. Nolan taps into a whole history of Greek and Shakespearean drama, where society is a manifestation of the individual (where something is rotten in Denmark; or Scotland plunges into unholy eternal night), and puts the Batman right where he belongs: centre stage. As such, he is here much more of a communal construct, a collaboration, than he appears in other versions of the Batman mythology. Nolan's universe makes it abundantly clear that although Bruce wears the mask, there would be no Batman without Alfred to stitch his wounds, without Lucius Fox to make his gadgets, Commissioner Gordon with whom to collaborate, the Mayor to turn a blind eye, Harvey Dent to advocate, the history and training of the League of Shadows and in this latest film: without Catwoman and a certain new young detective to rely upon. Nolan's vision is about the construction of a symbol, the kind of emblem in which a mass of people need to invest themselves to fight oppression and inspire change.  The whole trilogy is about fear how we as a peoples respond to cultures of fear, how we can strive to confront and not be governed by the faceless terrors that numb our souls to apathy. In many ways a superhero film has been the best (perhaps only) means through which to best explore in fiction our social crisis in the wake of the September 11 attacks and the subsequent 'War on Terror', providing an often uncompromising space in which to play out our negotiation of idealism and concessions of freedom for security. In Batman Begins Gotham is on the verge of tearing itself apart through a slow surrender to dread. While condemning the city to be purged with fire, Ra's al Ghul declares it a society that has degenerated into crime and inequity because it allowed itself to be terrorised by the will of the unjust. Good people have failed to stand up for what they believe, and fear has corrupted the very soul of the state a decay that is exacerbated and literalised at the end of the narrative when a nerve gas leads everyone to descend into paranoia and violence. Bruce Wayne, his own parents victims, therefore creates Batman as the answer to this demoralising fugue state, believing (while striving to maintain a moral code), that he can bring fear to those who would prey upon the fears of others. In his vigilante crusade he strives to show that criminals have reason to be scared when people refuse to be cowed. The second film however is a mediation upon the compromises that are made in the face of fear: those lines that we are willing to cross in pursuit of safety and order. The Joker, a creature of anarchic devastation tears through the city, seemingly unmotivated. He is terrorism personified: beyond reason and seeking to tear down civility by any means necessary. By the end of the film, in response to this chaos, there is no one who has not compromised themselves and their ethics: Gordon is willing to perpetuate a terrible lie for a greater good; Lucius agrees to see his technology turned into a violation of basic freedoms; Alfred burns the letter from Rachael, concealing a truth that he feels would be too painful for Bruce to know; and Harvey Dent (the bipolar face at the heart of the narrative) has his own very bad day... No one gets through that film both alive and unscarred by the events that they have survived. The Joker measures the human spirit with pressure, and although ultimately, it does not break it is damaged, perhaps irreparably by the experience. More than any other character, Batman, over the course of The Dark Knight,uses several morally and legally objectionable techniques to combat crime and terrorism he performs an act of extraordinary rendition; he savagely interrogates a prisoner;he constructs an elaborate bat sonar that invades to privacy of every citizen in a free state. He takes extreme measures, using tools of deceit that violate basic freedoms in order to protect the lives of his fellow citizens, but in the end it is not his amoral allowances that save Gotham, it is Gotham's spirit itself. When the Joker devises a moral power play in which two boats are tasked with killing others before killing themselves, neither side proves capable of making that final selfish choice to take another's life before their own. The Joker, despite being an astute observer of human behaviour, had misjudged the very fundamental good at the heart of humanity. We value the life of others, and in doing so validate the worth of our own. At the end of The Dark KnightBatman has not yet learned the lesson of his trilogy yet, and so takes upon himself a new lie, deciding to accept the blame for the death of Harvey Dent. In order to give the world a white knight to idolise and emulate, he provide an appealing lie around which Gotham could build a corrosive fiction: Batman is a villain; Harvey Dent was an uncorrupted victim and champion for good. In an effort to protect and inspire the good in others, Batman had compromised himself and sacrificed the very freedoms he would seek to cherish and at the beginning of The Dark Knight Rises we see where this deceit has led the city, and Bruce Wayne himself... Hence why Batman now has a limp.

The whole trilogy is about fear how we as a peoples respond to cultures of fear, how we can strive to confront and not be governed by the faceless terrors that numb our souls to apathy. In many ways a superhero film has been the best (perhaps only) means through which to best explore in fiction our social crisis in the wake of the September 11 attacks and the subsequent 'War on Terror', providing an often uncompromising space in which to play out our negotiation of idealism and concessions of freedom for security. In Batman Begins Gotham is on the verge of tearing itself apart through a slow surrender to dread. While condemning the city to be purged with fire, Ra's al Ghul declares it a society that has degenerated into crime and inequity because it allowed itself to be terrorised by the will of the unjust. Good people have failed to stand up for what they believe, and fear has corrupted the very soul of the state a decay that is exacerbated and literalised at the end of the narrative when a nerve gas leads everyone to descend into paranoia and violence. Bruce Wayne, his own parents victims, therefore creates Batman as the answer to this demoralising fugue state, believing (while striving to maintain a moral code), that he can bring fear to those who would prey upon the fears of others. In his vigilante crusade he strives to show that criminals have reason to be scared when people refuse to be cowed. The second film however is a mediation upon the compromises that are made in the face of fear: those lines that we are willing to cross in pursuit of safety and order. The Joker, a creature of anarchic devastation tears through the city, seemingly unmotivated. He is terrorism personified: beyond reason and seeking to tear down civility by any means necessary. By the end of the film, in response to this chaos, there is no one who has not compromised themselves and their ethics: Gordon is willing to perpetuate a terrible lie for a greater good; Lucius agrees to see his technology turned into a violation of basic freedoms; Alfred burns the letter from Rachael, concealing a truth that he feels would be too painful for Bruce to know; and Harvey Dent (the bipolar face at the heart of the narrative) has his own very bad day... No one gets through that film both alive and unscarred by the events that they have survived. The Joker measures the human spirit with pressure, and although ultimately, it does not break it is damaged, perhaps irreparably by the experience. More than any other character, Batman, over the course of The Dark Knight,uses several morally and legally objectionable techniques to combat crime and terrorism he performs an act of extraordinary rendition; he savagely interrogates a prisoner;he constructs an elaborate bat sonar that invades to privacy of every citizen in a free state. He takes extreme measures, using tools of deceit that violate basic freedoms in order to protect the lives of his fellow citizens, but in the end it is not his amoral allowances that save Gotham, it is Gotham's spirit itself. When the Joker devises a moral power play in which two boats are tasked with killing others before killing themselves, neither side proves capable of making that final selfish choice to take another's life before their own. The Joker, despite being an astute observer of human behaviour, had misjudged the very fundamental good at the heart of humanity. We value the life of others, and in doing so validate the worth of our own. At the end of The Dark KnightBatman has not yet learned the lesson of his trilogy yet, and so takes upon himself a new lie, deciding to accept the blame for the death of Harvey Dent. In order to give the world a white knight to idolise and emulate, he provide an appealing lie around which Gotham could build a corrosive fiction: Batman is a villain; Harvey Dent was an uncorrupted victim and champion for good. In an effort to protect and inspire the good in others, Batman had compromised himself and sacrificed the very freedoms he would seek to cherish and at the beginning of The Dark Knight Rises we see where this deceit has led the city, and Bruce Wayne himself... Hence why Batman now has a limp.  Indeed, everyone starts the concluding chapter still nursing the metaphorical and literal wounds of the previous film: Jim Gordon is a weathered shell of a man, weighed down by the enormity of the lie he has perpetuated in the city's idolatry of Harvey Dent; Alfred lives with the sorrow of seeing the child left in his care now a sallow hermit wallowing in grief and self-loathing; even Lucius Fox sits chafing in a boardroom, stunted from growing the company he stewards and itching to unleash a batch of new toys with comical 'Bat' prefixes. And Bruce Wayne, physically worn down and spiritual sapped, a Spruce Goose blueprint away from total breakdown, awaits the excuse to suit up again and end his suffering via street-punk assisted suicide. Fear has pressed in on each of these people; it has led them to compromise themselves; led them to fabricate lies; to hide beneath falsehoods in the service of a 'greater good'. And so, in contrast, this final act in the trilogy is about finding a way, at last, to genuinely ascend beyond the governance and definition of fear. Indeed, this theme of ascension is built into every aspect of the text: in Bruce Wayne's climb from prison; in Batman's rise from being broken and left for dead; from the rise of the citizenry (both in the wake of Bane's fabricated social inequity, to their subsequent genuine pursuit for justice); to the restoration of the police officers who crawl back into the light to restore order; from Selina Kyle striving to escape the limitations of her identity, finally inspired to stand for something more than herself; to John Blake stepping onto a platform that lifts him toward a whole new path in life... The film therefore concerns itself with exploring the way in which society can transcend intractable cycles of behaviour, how it can confront truth and ascend beyond the stifling limitations of moral concession. The opening shot of the film is a Batman symbol being formed in cracking ice, and it's the perfect metaphor for this narrative: the glacial stress of all this injustice in the name of order, all this compromise to terror in the name of peace, has been building for some time, and the events of this movie are its final cathartic eruption. Society will be changed, people die, but they will die knowing that they fought for what was right, not bowed down or compromised, finally not permitting themselves to be dictated to by fear.

Indeed, everyone starts the concluding chapter still nursing the metaphorical and literal wounds of the previous film: Jim Gordon is a weathered shell of a man, weighed down by the enormity of the lie he has perpetuated in the city's idolatry of Harvey Dent; Alfred lives with the sorrow of seeing the child left in his care now a sallow hermit wallowing in grief and self-loathing; even Lucius Fox sits chafing in a boardroom, stunted from growing the company he stewards and itching to unleash a batch of new toys with comical 'Bat' prefixes. And Bruce Wayne, physically worn down and spiritual sapped, a Spruce Goose blueprint away from total breakdown, awaits the excuse to suit up again and end his suffering via street-punk assisted suicide. Fear has pressed in on each of these people; it has led them to compromise themselves; led them to fabricate lies; to hide beneath falsehoods in the service of a 'greater good'. And so, in contrast, this final act in the trilogy is about finding a way, at last, to genuinely ascend beyond the governance and definition of fear. Indeed, this theme of ascension is built into every aspect of the text: in Bruce Wayne's climb from prison; in Batman's rise from being broken and left for dead; from the rise of the citizenry (both in the wake of Bane's fabricated social inequity, to their subsequent genuine pursuit for justice); to the restoration of the police officers who crawl back into the light to restore order; from Selina Kyle striving to escape the limitations of her identity, finally inspired to stand for something more than herself; to John Blake stepping onto a platform that lifts him toward a whole new path in life... The film therefore concerns itself with exploring the way in which society can transcend intractable cycles of behaviour, how it can confront truth and ascend beyond the stifling limitations of moral concession. The opening shot of the film is a Batman symbol being formed in cracking ice, and it's the perfect metaphor for this narrative: the glacial stress of all this injustice in the name of order, all this compromise to terror in the name of peace, has been building for some time, and the events of this movie are its final cathartic eruption. Society will be changed, people die, but they will die knowing that they fought for what was right, not bowed down or compromised, finally not permitting themselves to be dictated to by fear.  Foremost, as the narrative reveals, division and demonization does not offer an answer to the threat of injustice. Some have argued that the 'uprising' depicted in the film concerns class injustice (a number of reviewers have accused Nolan of making some definitive statement on the Occupy Wall Street movement), but it should be remembered that the instigator, Bane, is not at all concerned with the issues of the 'rich' versus 'poor'. Indeed, he'd be fine if the conflict tearing at Gotham's citizens was My Little Ponies versus Transformers. All Bane seeks to do is sew social division through the demonization of the other, whatever that other may be. It is a tactic of partition in which terror and suspicion allow morality to be negated in yet another toxically flawed pursuit of 'justice' another cycle of fear-mongering that leads to only more recrimination and amorality. It is only by wholly dissolving such falsehoods, the narrative reveals, that there can be any hope for healing a fractured society. As Alfred states at a pivotal moment in Bruce's journey: it is now time for the truth to have its day, to trust that as a society we are all adult enough to deal with it.**** And that's why in this film we no longer only see Batman in the shadows. By the end he's standing in broad daylight, no longer just a redirected piece of the dark a product of fear used to terrify the fearsome he is now a symbol of so much more. He is resilience; sacrifice; a belief in a cause greater than oneself that can only be achieved by remaining just, and not weaponising deceit for the 'greater good'. In this context it is clear that everything spoken of as 'supporting' rendition, covert spying, and media control in The Dark Knight was merely setting the stage for this, the actual message of these films. Batman, manifestation of our culture's soul, was driven to his breaking point was almost broken but in clawing his way back from it, by not tipping over into absolute compromise, he is able to reassert himself, to stand for something more. Nolan therefore finds a way to end the Batman mythos, while keeping its spirit alive. The Bruce Wayne Batman 'dies' sacrificing himself for the city, taking upon himself the devastation that such recrimination and division has wrought but in that act of sacrifice he inspires others. Thus Batman the myth does not die, instead he erupts in a messianic dispersal. More than just a man in a suit, he reveals himself to be an idea, a symbol, one that in its cultural diffusion has more power, more influence, than a single man with a grapple gun and pointy ears ever could. The symbolism of light throughout the work, climbing out of darkness, longingly yearning to ascend, both culturally and personally, from a state of mire and oppression to an illuminated burst of freedom, is one potently literalised with a ball of white igniting the horizon. Batman reveals himself to be Prometheus: he snatches the light from the seemingly all-powerful and distributes it to the frightened masses cowering in fear.

Foremost, as the narrative reveals, division and demonization does not offer an answer to the threat of injustice. Some have argued that the 'uprising' depicted in the film concerns class injustice (a number of reviewers have accused Nolan of making some definitive statement on the Occupy Wall Street movement), but it should be remembered that the instigator, Bane, is not at all concerned with the issues of the 'rich' versus 'poor'. Indeed, he'd be fine if the conflict tearing at Gotham's citizens was My Little Ponies versus Transformers. All Bane seeks to do is sew social division through the demonization of the other, whatever that other may be. It is a tactic of partition in which terror and suspicion allow morality to be negated in yet another toxically flawed pursuit of 'justice' another cycle of fear-mongering that leads to only more recrimination and amorality. It is only by wholly dissolving such falsehoods, the narrative reveals, that there can be any hope for healing a fractured society. As Alfred states at a pivotal moment in Bruce's journey: it is now time for the truth to have its day, to trust that as a society we are all adult enough to deal with it.**** And that's why in this film we no longer only see Batman in the shadows. By the end he's standing in broad daylight, no longer just a redirected piece of the dark a product of fear used to terrify the fearsome he is now a symbol of so much more. He is resilience; sacrifice; a belief in a cause greater than oneself that can only be achieved by remaining just, and not weaponising deceit for the 'greater good'. In this context it is clear that everything spoken of as 'supporting' rendition, covert spying, and media control in The Dark Knight was merely setting the stage for this, the actual message of these films. Batman, manifestation of our culture's soul, was driven to his breaking point was almost broken but in clawing his way back from it, by not tipping over into absolute compromise, he is able to reassert himself, to stand for something more. Nolan therefore finds a way to end the Batman mythos, while keeping its spirit alive. The Bruce Wayne Batman 'dies' sacrificing himself for the city, taking upon himself the devastation that such recrimination and division has wrought but in that act of sacrifice he inspires others. Thus Batman the myth does not die, instead he erupts in a messianic dispersal. More than just a man in a suit, he reveals himself to be an idea, a symbol, one that in its cultural diffusion has more power, more influence, than a single man with a grapple gun and pointy ears ever could. The symbolism of light throughout the work, climbing out of darkness, longingly yearning to ascend, both culturally and personally, from a state of mire and oppression to an illuminated burst of freedom, is one potently literalised with a ball of white igniting the horizon. Batman reveals himself to be Prometheus: he snatches the light from the seemingly all-powerful and distributes it to the frightened masses cowering in fear.  Batman, throughout the three films but most particularly in this final statement of purpose is a construct, the collaboration of a community (from the physical man in Bruce; to the funds from his family; to the partnership with the police force in Gordon; the collaboration with the DA in Dent; the gadgets from Lucius Fox; the medical treatment from Alfred; the mask identity perpetuated by Alfred; the strategising of purchases from Alfred; the sandwiches Alfred makes; Alfred's building a freaking Batcave ...um, Alfred is kind of important). Anyhoo: Batman here is a pastiche figure, one that, although tethered to the body of one man, could not operate without the support structure of many. So blowing him up annihilating the individual to bring salvation to the many literally disperses him back amongst the populace that brought him into being. Batman, in an act of destruction, is ironically only then truly created: now no longer localised around one perishable man and a bunker of gadgets, but ascending to the role of a guiding aspiration. Postmodern Prometheus, with that final illuminatory burst he transcends the status of urban legend and becomes an ideological compass, now so engrained in the minds of the people, so central to their faith in themselves, that he comes to be immortalised in statue form. He stands at the heart of their city, representative of a newly restored longing to fight oppression, to remind the populace they no longer need be bowed by fear; that in their unity, and their belief in justice, such measures need never be necessary again. It may, of course, seem peculiar that at the end Gotham has been left almost a wasteland an entire devastated infrastructure, criminals wandering the street, while erstwhile protector Bruce Wayne appears to be laughing it up, sipping espressos in the European sun with a pretty lady. But rather than abandoning his post, he knows finally that he has given everything that he can to that role. The Batman has ascended beyond him, and the best thing that he can do, finally, is to embrace that newfound life that Selina, and Alfred's long-held wish for peace, now offer him. Wayne originally became Batman, he tells Blake, because he wanted to be a symbol, a symbol to frighten those who would bring fear to others. Criminals would not know who or where he was: Batman would be real: he would be out there; and he could be anyone. But the series reveals that this kind of vigilantism is short term. Fear fighting fear; terror begetting only more (if displaced) terror: it is in such a landscape that creatures like the Joker prosper, an entity vomited up from the darkest recesses of the human psyche, to shake the cages of the rational world and expose the noxious raging id beneath the demure surface of the superego. Ultimately, order cannot not be imposed upon chaos through deception, by using the tools of terror to combat terrorism.

Batman, throughout the three films but most particularly in this final statement of purpose is a construct, the collaboration of a community (from the physical man in Bruce; to the funds from his family; to the partnership with the police force in Gordon; the collaboration with the DA in Dent; the gadgets from Lucius Fox; the medical treatment from Alfred; the mask identity perpetuated by Alfred; the strategising of purchases from Alfred; the sandwiches Alfred makes; Alfred's building a freaking Batcave ...um, Alfred is kind of important). Anyhoo: Batman here is a pastiche figure, one that, although tethered to the body of one man, could not operate without the support structure of many. So blowing him up annihilating the individual to bring salvation to the many literally disperses him back amongst the populace that brought him into being. Batman, in an act of destruction, is ironically only then truly created: now no longer localised around one perishable man and a bunker of gadgets, but ascending to the role of a guiding aspiration. Postmodern Prometheus, with that final illuminatory burst he transcends the status of urban legend and becomes an ideological compass, now so engrained in the minds of the people, so central to their faith in themselves, that he comes to be immortalised in statue form. He stands at the heart of their city, representative of a newly restored longing to fight oppression, to remind the populace they no longer need be bowed by fear; that in their unity, and their belief in justice, such measures need never be necessary again. It may, of course, seem peculiar that at the end Gotham has been left almost a wasteland an entire devastated infrastructure, criminals wandering the street, while erstwhile protector Bruce Wayne appears to be laughing it up, sipping espressos in the European sun with a pretty lady. But rather than abandoning his post, he knows finally that he has given everything that he can to that role. The Batman has ascended beyond him, and the best thing that he can do, finally, is to embrace that newfound life that Selina, and Alfred's long-held wish for peace, now offer him. Wayne originally became Batman, he tells Blake, because he wanted to be a symbol, a symbol to frighten those who would bring fear to others. Criminals would not know who or where he was: Batman would be real: he would be out there; and he could be anyone. But the series reveals that this kind of vigilantism is short term. Fear fighting fear; terror begetting only more (if displaced) terror: it is in such a landscape that creatures like the Joker prosper, an entity vomited up from the darkest recesses of the human psyche, to shake the cages of the rational world and expose the noxious raging id beneath the demure surface of the superego. Ultimately, order cannot not be imposed upon chaos through deception, by using the tools of terror to combat terrorism.  Batman may have begun as a tool to redirect horror, but the concluding film shows that Batman's ultimate purpose was to reveal to us how to dissolve fear itself. The only way in which to combat terror, to overcome dread, is to bring it into the light. As Alfred says, pleading for Wayne not to waste himself in an act of meaningless self-immolation: 'I am using the truth, Master Wayne. Maybe it's time we all stop trying to outsmart the truth and let it have its day.' And in coming into the light, stepping out of the shadows in order to sacrifice himself to something greater, Batman does indeed become a true symbol: Batman is real: he is in here; and he is everyone. No longer would people live under the yoke of lies to numb themselves from responsibility. Batman is in all of us, an ideal, a truth to be cherished, and a heroism we all can all aspire to uphold. Batman, Postmodern Prometheus, sinks himself into shadow in order to ultimately deliver us light. And that is why Bruce Wayne could not die. Death would be too easy; death would be yet another slide into an easy fix; a surrender to the nihilistic self-destructive impulse that his grief had driven him toward. The harder thing, he comes to see, is living: fighting each day to stand for something, to prosper and do good. By finally embracing his place alongside his fellow humanity, Bruce finds the strength to do the most remarkable thing of all: to believe in life itself. And besides, in some versions of the ancient myth, even Prometheus gets untied from the rock. * http://whatculture.com/comics/batman-the-new-gods-of-the-super-heroic.php ** In Greek Prometheus' name translates as 'fore thinker'; he is a character who uses his brains to plan out his actions. Batman is known for his physical resilience and strength, sure, but he is foremost the Greatest Detective. It is his mind that sets him apart from the other heroes, and his subversive cunning that proves his most valuable tool. *** One analysis in particular by Film Crit Hulk (who writes under the gimmick of typing in all caps), offers a rather mystifying reading of the narrative in which he dismisses the film as 'cynical', accusing it of having no narrative cohesion whatsoever. He does, however, base much of this upon his utterly subjective speculation about what he thinks Nolan might have done with the story had Heath Ledger lived. **** A moment in which Michael Caine is acting his heart out. I salute you, sir.

Batman may have begun as a tool to redirect horror, but the concluding film shows that Batman's ultimate purpose was to reveal to us how to dissolve fear itself. The only way in which to combat terror, to overcome dread, is to bring it into the light. As Alfred says, pleading for Wayne not to waste himself in an act of meaningless self-immolation: 'I am using the truth, Master Wayne. Maybe it's time we all stop trying to outsmart the truth and let it have its day.' And in coming into the light, stepping out of the shadows in order to sacrifice himself to something greater, Batman does indeed become a true symbol: Batman is real: he is in here; and he is everyone. No longer would people live under the yoke of lies to numb themselves from responsibility. Batman is in all of us, an ideal, a truth to be cherished, and a heroism we all can all aspire to uphold. Batman, Postmodern Prometheus, sinks himself into shadow in order to ultimately deliver us light. And that is why Bruce Wayne could not die. Death would be too easy; death would be yet another slide into an easy fix; a surrender to the nihilistic self-destructive impulse that his grief had driven him toward. The harder thing, he comes to see, is living: fighting each day to stand for something, to prosper and do good. By finally embracing his place alongside his fellow humanity, Bruce finds the strength to do the most remarkable thing of all: to believe in life itself. And besides, in some versions of the ancient myth, even Prometheus gets untied from the rock. * http://whatculture.com/comics/batman-the-new-gods-of-the-super-heroic.php ** In Greek Prometheus' name translates as 'fore thinker'; he is a character who uses his brains to plan out his actions. Batman is known for his physical resilience and strength, sure, but he is foremost the Greatest Detective. It is his mind that sets him apart from the other heroes, and his subversive cunning that proves his most valuable tool. *** One analysis in particular by Film Crit Hulk (who writes under the gimmick of typing in all caps), offers a rather mystifying reading of the narrative in which he dismisses the film as 'cynical', accusing it of having no narrative cohesion whatsoever. He does, however, base much of this upon his utterly subjective speculation about what he thinks Nolan might have done with the story had Heath Ledger lived. **** A moment in which Michael Caine is acting his heart out. I salute you, sir.