Review: Thimbleweed Park

Pinch yourself: it really is a new Ron Gilbert LucasArts classic.

As I write this review, the skeletal grimace of Monkey Island 2's chief antagonist LéChuck peers menacingly from a beautifully framed print on my office wall. A huge tome rests in one corner of my desk - Rogue Leaders: The History of LucasArts - its tasteful lenticular cover flashing a series of adventure game greats from Guybrush Threepwood to Purple Tentacle with every head swivel. Other artefacts furnish the room; a boxed copy of Full Throttle here, a Steve Purcell signed poster there. Everywhere I look I'm repeatedly reminded of an undying passion for point 'n' click.

Benighted by this bias, perhaps I'm not the ideal candidate to offer an objective opinion of Thimbleweed Park - a project specifically designed to be like "an undiscovered classic LucasArts' adventure game you'd never played before."

But maybe the opposite is true; Thimbleweed Park is basically tailor-made to my predilections - and as a result, yearns for my approval at every turn.

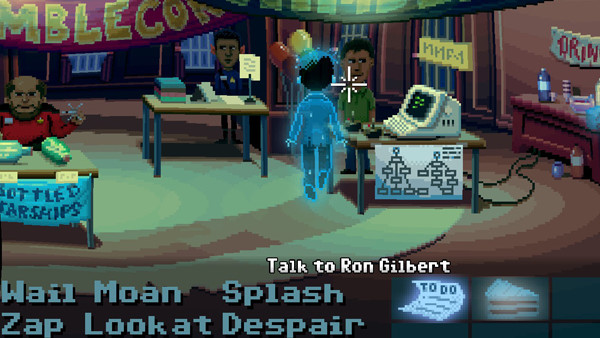

It couldn't be any more old school if it were the University of Bologna. The SCUMM interface makes a triumphant return in its most cherished form, and the pixel-art pastiches are achingly nostalgic. For better or worse, traditional puzzles are legion, flying in the face of the modern wisdom which castigates their 'antiquated' nature in favour of hands grasped so tightly they're as blue as a rapidly-pixelating corpse. Even the options menu strives to appease those looking for a fossilised lump of hitherto undiscovered adventure game amber, offering 'classic' style fonts and interface lifted straight from The Secret of Monkey Island. It's the sort of blissful wish-fulfillment provided by only the best blue-ribbon genies.

In every regard the game is an authentic homage, but paradoxically it also plays host to irreverent satire. References to classics of the past fall thick and fast (Maniac Mansion is a frequent callback), and the fourth-wall crumbles almost immediately, as characters abandon their personal agendas to extol the virtues of the forgotten genre. The game opens up an ancient, bitter conflict between the long-dead Sierra and similarly defunct LucasArts, while one of the protagonists chases her ambition to make adventure games for the famed 'Mmucasflem Games'.

Perhaps this overt self-awareness pushes just a little too hard; with it comes a worrying sense that maybe, just maybe, through its smug lauding of point 'n' click, Thimbleweed Park is stuffing its super-deformed head up its own arse. But you can't deny its sincerity, and brilliantly, the narrative even locates an explanation for this pomposity-straddling panegyric. (And since this review was first published, an option has even been added to turn off 'annoying in-jokes' for those overwhelmed by the retro references).

That said, Thimbleweed Park is preaching to a Commodore 64-cradling choir in this department anyway, the phalanx of fans who'll have spared not a single second in snapping the game up the moment it was released. Gilbert's 'unearthed relic' is essentially selling bananas to monkeys, when it should be trying to convince a whole other set of gamers of this exotic fruit besides their usual apples. Relying on such niche appeal can be a dangerous thing, though perhaps the army of Kickstarter backers who stumped up over half-a-million dollars suggests otherwise.

Fortunately, the game does make some slight concessions for the uninitiated - ones which even veteran adventure gamers are sure to appreciate. They're small, subtle touches - holding the mouse button down to run, having journals to prevent you becoming irredeemably lost for your next objective - but they're ones which alleviate some frustrations non-genre fans simply can't stomach.

That's where the compromises end, however, and the way the rest of the game plays is completely faithful to its predecessors, warts 'n' all. Inventory-based brainteasers are numerous, adopting a degree of complexity and creativity rarely seen in the genre since its golden age. Yet they're never obtuse enough to completely grind the game to a halt; not once does an elephant need adumbrating to progress, or is Rune Goldberg's rubber duck employed as a fishing rod. Instead, the head-scratchers have almost universally rational solutions, sometimes tricky, but seldom unfair.

One or two stretch the imagination a little - most of them involve remembering you have a ghost at your disposal - but a facet which once saw the genre excoriated is now something to be savoured. The satisfaction of defogging frustration with a hard-fought solution is something that has been absent from gaming - even adventure gaming - since the glory days, and it isn't just misplaced nostalgia which makes this restored feeling so pleasurable. Furthermore, any puzzle that has you stumped in Thimbleweed Park is eminently forgivable the moment you finally unravel it, such is the undercurrent of sensible logic permeating their design.

Less forgivable are the numerous 'red herring' items, always considered something of a cardinal sin in adventure game design. Conditioned kleptomania means most players will snag everything not bolted down anyway, so this is rarely a huge issue, but it can becloud objectives from time to time. Why have I worked so tirelessly to obtain this paperweight under the assumption it can prop open a door, when it's actually entirely superfluous? What am I lugging this cabbage around for? Yes, it can break the suspension of disbelief when a protagonist acquires only the exact items they need, but there's a very valid reason this became convention.

Unquestionably the weakest aspect of Thimbleweed Park is the necessity to shuffle between five different playable characters. Clearly a tribute to Maniac Mansion (and to a lesser extent, Day of the Tentacle), the multi-person set-up, whilst ostensibly offering a freedom of progression, actually makes proceedings more confusing. Unlike Tentacle, where each character was anchored in time and worked relatively independently, Thimbleweed's cast share a world but divide its inventory and tasks. Having to micro-manage items can be a particular chore, especially when it means ferrying one character to the other side of the map for the sole purpose.

The greater issue with this omnium-gatherum is the shared consciousness which only exists in the player's mind, and not in that of the characters. Though it makes perfect sense in the context of my immediate goals, it's never clear why a vulgar clown should unquestionably hand a wallet over to a federal agent, or a hint guide to a young games designer, neither of whom he has engaged in any prior interaction with. Without wanting to spoil Thimbleweed Park's wonderful reveal, there is eventually a superb narrative explanation for all this, though it literally comes at the close, by which point such annoyances have already tarnished the game just a smidge.

I'd have shed few tears had foul-mouthed clown Ransome been removed from this quintet, but the rest of the actors are indispensable to Thimbleweed Park's charm. A couple come dangerously close to annoying-a-reno-a-who, but on the whole the writing recaptures the whimsical quirkiness which made LucasArt's classics stand apart. It isn't always high-brow stuff - sometimes it even descends into puerility - but the game's script is knowingly written for adults, free from the hackneyed trappings of virtually every other genre in the industry. As a result, it's inventive, entertaining, and totally infectious. Diggin'!

Thimbleweed Park's narrative threads begin to fray in its latter half, an understandable trade-off for its dizzyingly substantial opening acts, but the denouement more than makes up for it. It's a twist you can see a mile off without a telescope prior to its reveal, but the fresh light it casts on everything which precedes is startling. Suddenly, every unanswered question, every criticism, and even the very nature of the game itself are given a transformed meaning. It's post-modernism at its finest, a stunning development which elevates the game beyond its regular off-beat facade.

Ultimately, Thimbleweed Park delivers on its promise to quench the thirst of completely parched adventure game fans, and it does so wholesale. However, it equally stands as a heartfelt testament to a lost philosophy of video game design. Mechanically, it might be dated in places - sometimes intentionally, sometimes not. Yet it's everything it should be, and crucially, everything it wants to be. In an era where non-mainstream games have to shriek like banshees for attention above the usual AAA tedium, Thimbleweed Park does so louder than any, with a cathartic exultation of: "we're entitled to be here too."

Adventure fans need no convincing to buy this, but it's crucial everybody else gives it a go too. We need games like Thimbleweed Park to exist, just as much as they deserve to.