5. The Pop Art Age - 1966-1974

20th Century FoxOriginally airing in 1961 ITV's The Avengers (no relation to the Marvel Comics team that began in 1963) was a fairly conventional TV detective show. By 1965 and the arrival of its most famous cast member, Diana Rigg as cool asskicker Emma Peel, and its prime time US broadcast on ABC The Avengers had become a very different show, its clean and simple storytelling replaced by bizarre elements of science fiction and eccentric fantasy, all with a hyper stylised look. The age of Pop Art TV had begun. The Avengers may have begun on TV (comic strips ran in magazines through the mid-late 1960s), but it is indicative of the way screen adventure characters were changing and that included the shift from the old fashioned heroics of George Reeves' Superman to the arch silliness of Adam West's Batman, which aired on ABC from 1966 a year after the network began showing The Avengers. Wartime austerity had been replaced by a new affluence, while that age's black and white morality that allowed for simply drawn heroes had given way to the uncertainties and dissatisfaction of the Cold War and Vietnam. With the likes of Roy Lichtenstein's Whaam! both elevating comic visuals to fine art and reducing comic styles to parody, the stage was set for screen narratives that were hip, stylised and full of ironic oddballs covering an undercurrent of social subversion. This was the cultural climate that allowed Batman producer William Dozier to deliver a show that presented superhero adventures in a high camp, self parodic fashion. Even though West's Batman delivered moral lessons to the kids it was always with a detached sense of irony and a raised eyebrow (literally in the case of the latter as they were drawn onto his cowl). With America going through something of an identity crisis in this period, much of this stylish, subversive comic book material came from overseas. Fantomas, as popular with the pop artists as he had been with earlier surrealists, had returned to cinemas with a trio of light, Bond-style adventures from 1964-66 and his cool criminal anti-hero style influenced many Euro-comics and films of the day. The vengeful skull masked killer Kriminal first appeared in Italian comics in 1964 and was brought to screen in 1966 by giallo director Umberto Lenzi in lighter, more caper style escapades, swiftly followed by fellow horror maestro Mario Bava's similar Danger: Diabolik in 1968. The eroticism of the Kriminal comics often saw them in trouble with the censors, an increasingly common phenomenon in the more liberated 60s. Jean-Claude Forest's Barbarella, appearing in French comics in V magazine from 1962, was the poster girl for the sexually free 60s woman in comics. The sexy space romp transferred to screen in Roger Vadim's 1968 film starring popular pin-up Jane Fonda, pre-political activism and Oscars. It was not a success, but gained a cult audience over time. Less well known than Barbarella now, Britain's Modesty Blaise nevertheless enjoyed a moderate commercial success with an Avengers-esque surreal sexy spy-fi film adaptation starring Antonioni muse Monica Vitti in 1966. Like Barbarella, though, the film left critics non-plussed. The logical end point of these increasingly cultish sexualised comic films was adaptations of more explicit underground comics. The 1972 film of buttock fixated Robert Crumb's Fritz the Cat (made by future Lord of the Rings director Ralph Bakshi) was the first animated film to receive an American X rating and the most successful independent animation to date. A sequel followed in 1974, the same year as Flesh Gordon, the first explicitly pornographic mainstream comic adaptation. In its nostalgia for the simple fun adventures in film serials of the Cliffhanger Age, though, this porno anticipated the clean cut trends of the next era.

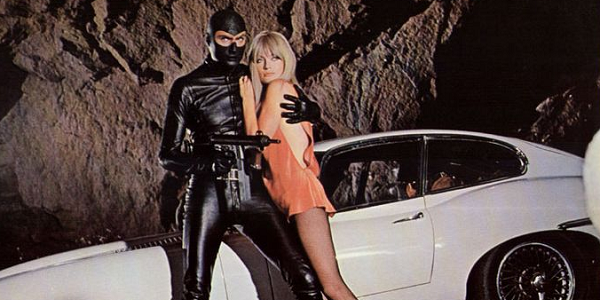

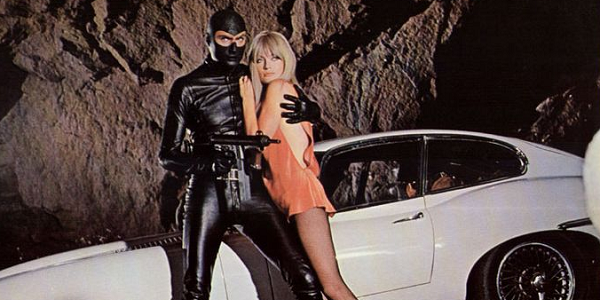

Key Film: Danger: Diabolik (1968)

Dino De Laurentiis/ParamountDiabolik, inspired by creator Angela Giusani findng a Fantomas novel on a train, predated Kriminal as a comic and obviously inspired it. As a film Diabolik came second, but was a far superior take on the material. Bava had a stronger visual sense than Lenzi and made a film whose stylish pop art visuals and subversive tone would fit the era's style perfectly, inviting audiences to root for a cool anti-hero rather than the dogged detective in pursuit.

20th Century FoxOriginally airing in 1961 ITV's The Avengers (no relation to the Marvel Comics team that began in 1963) was a fairly conventional TV detective show. By 1965 and the arrival of its most famous cast member, Diana Rigg as cool asskicker Emma Peel, and its prime time US broadcast on ABC The Avengers had become a very different show, its clean and simple storytelling replaced by bizarre elements of science fiction and eccentric fantasy, all with a hyper stylised look. The age of Pop Art TV had begun. The Avengers may have begun on TV (comic strips ran in magazines through the mid-late 1960s), but it is indicative of the way screen adventure characters were changing and that included the shift from the old fashioned heroics of George Reeves' Superman to the arch silliness of Adam West's Batman, which aired on ABC from 1966 a year after the network began showing The Avengers. Wartime austerity had been replaced by a new affluence, while that age's black and white morality that allowed for simply drawn heroes had given way to the uncertainties and dissatisfaction of the Cold War and Vietnam. With the likes of Roy Lichtenstein's Whaam! both elevating comic visuals to fine art and reducing comic styles to parody, the stage was set for screen narratives that were hip, stylised and full of ironic oddballs covering an undercurrent of social subversion. This was the cultural climate that allowed Batman producer William Dozier to deliver a show that presented superhero adventures in a high camp, self parodic fashion. Even though West's Batman delivered moral lessons to the kids it was always with a detached sense of irony and a raised eyebrow (literally in the case of the latter as they were drawn onto his cowl). With America going through something of an identity crisis in this period, much of this stylish, subversive comic book material came from overseas. Fantomas, as popular with the pop artists as he had been with earlier surrealists, had returned to cinemas with a trio of light, Bond-style adventures from 1964-66 and his cool criminal anti-hero style influenced many Euro-comics and films of the day. The vengeful skull masked killer Kriminal first appeared in Italian comics in 1964 and was brought to screen in 1966 by giallo director Umberto Lenzi in lighter, more caper style escapades, swiftly followed by fellow horror maestro Mario Bava's similar Danger: Diabolik in 1968. The eroticism of the Kriminal comics often saw them in trouble with the censors, an increasingly common phenomenon in the more liberated 60s. Jean-Claude Forest's Barbarella, appearing in French comics in V magazine from 1962, was the poster girl for the sexually free 60s woman in comics. The sexy space romp transferred to screen in Roger Vadim's 1968 film starring popular pin-up Jane Fonda, pre-political activism and Oscars. It was not a success, but gained a cult audience over time. Less well known than Barbarella now, Britain's Modesty Blaise nevertheless enjoyed a moderate commercial success with an Avengers-esque surreal sexy spy-fi film adaptation starring Antonioni muse Monica Vitti in 1966. Like Barbarella, though, the film left critics non-plussed. The logical end point of these increasingly cultish sexualised comic films was adaptations of more explicit underground comics. The 1972 film of buttock fixated Robert Crumb's Fritz the Cat (made by future Lord of the Rings director Ralph Bakshi) was the first animated film to receive an American X rating and the most successful independent animation to date. A sequel followed in 1974, the same year as Flesh Gordon, the first explicitly pornographic mainstream comic adaptation. In its nostalgia for the simple fun adventures in film serials of the Cliffhanger Age, though, this porno anticipated the clean cut trends of the next era.

20th Century FoxOriginally airing in 1961 ITV's The Avengers (no relation to the Marvel Comics team that began in 1963) was a fairly conventional TV detective show. By 1965 and the arrival of its most famous cast member, Diana Rigg as cool asskicker Emma Peel, and its prime time US broadcast on ABC The Avengers had become a very different show, its clean and simple storytelling replaced by bizarre elements of science fiction and eccentric fantasy, all with a hyper stylised look. The age of Pop Art TV had begun. The Avengers may have begun on TV (comic strips ran in magazines through the mid-late 1960s), but it is indicative of the way screen adventure characters were changing and that included the shift from the old fashioned heroics of George Reeves' Superman to the arch silliness of Adam West's Batman, which aired on ABC from 1966 a year after the network began showing The Avengers. Wartime austerity had been replaced by a new affluence, while that age's black and white morality that allowed for simply drawn heroes had given way to the uncertainties and dissatisfaction of the Cold War and Vietnam. With the likes of Roy Lichtenstein's Whaam! both elevating comic visuals to fine art and reducing comic styles to parody, the stage was set for screen narratives that were hip, stylised and full of ironic oddballs covering an undercurrent of social subversion. This was the cultural climate that allowed Batman producer William Dozier to deliver a show that presented superhero adventures in a high camp, self parodic fashion. Even though West's Batman delivered moral lessons to the kids it was always with a detached sense of irony and a raised eyebrow (literally in the case of the latter as they were drawn onto his cowl). With America going through something of an identity crisis in this period, much of this stylish, subversive comic book material came from overseas. Fantomas, as popular with the pop artists as he had been with earlier surrealists, had returned to cinemas with a trio of light, Bond-style adventures from 1964-66 and his cool criminal anti-hero style influenced many Euro-comics and films of the day. The vengeful skull masked killer Kriminal first appeared in Italian comics in 1964 and was brought to screen in 1966 by giallo director Umberto Lenzi in lighter, more caper style escapades, swiftly followed by fellow horror maestro Mario Bava's similar Danger: Diabolik in 1968. The eroticism of the Kriminal comics often saw them in trouble with the censors, an increasingly common phenomenon in the more liberated 60s. Jean-Claude Forest's Barbarella, appearing in French comics in V magazine from 1962, was the poster girl for the sexually free 60s woman in comics. The sexy space romp transferred to screen in Roger Vadim's 1968 film starring popular pin-up Jane Fonda, pre-political activism and Oscars. It was not a success, but gained a cult audience over time. Less well known than Barbarella now, Britain's Modesty Blaise nevertheless enjoyed a moderate commercial success with an Avengers-esque surreal sexy spy-fi film adaptation starring Antonioni muse Monica Vitti in 1966. Like Barbarella, though, the film left critics non-plussed. The logical end point of these increasingly cultish sexualised comic films was adaptations of more explicit underground comics. The 1972 film of buttock fixated Robert Crumb's Fritz the Cat (made by future Lord of the Rings director Ralph Bakshi) was the first animated film to receive an American X rating and the most successful independent animation to date. A sequel followed in 1974, the same year as Flesh Gordon, the first explicitly pornographic mainstream comic adaptation. In its nostalgia for the simple fun adventures in film serials of the Cliffhanger Age, though, this porno anticipated the clean cut trends of the next era.  Dino De Laurentiis/ParamountDiabolik, inspired by creator Angela Giusani findng a Fantomas novel on a train, predated Kriminal as a comic and obviously inspired it. As a film Diabolik came second, but was a far superior take on the material. Bava had a stronger visual sense than Lenzi and made a film whose stylish pop art visuals and subversive tone would fit the era's style perfectly, inviting audiences to root for a cool anti-hero rather than the dogged detective in pursuit.

Dino De Laurentiis/ParamountDiabolik, inspired by creator Angela Giusani findng a Fantomas novel on a train, predated Kriminal as a comic and obviously inspired it. As a film Diabolik came second, but was a far superior take on the material. Bava had a stronger visual sense than Lenzi and made a film whose stylish pop art visuals and subversive tone would fit the era's style perfectly, inviting audiences to root for a cool anti-hero rather than the dogged detective in pursuit.