This Men In Black Secret Will Blow You Mind (For The Worst Reasons)

Hollywood Accounting - The Summer Blockbusters That Somehow Make No Money

So, what does Hollywood Accounting actually entail? Speaking to NPR in 2010 on the Planet Money podcast, Edward J. Epstein, the author of The Hollywood Economist (which dives into the dark financial arts of the movie business), described the process of said practice and how films can generate millions against a smaller budget and still end up making a net loss.

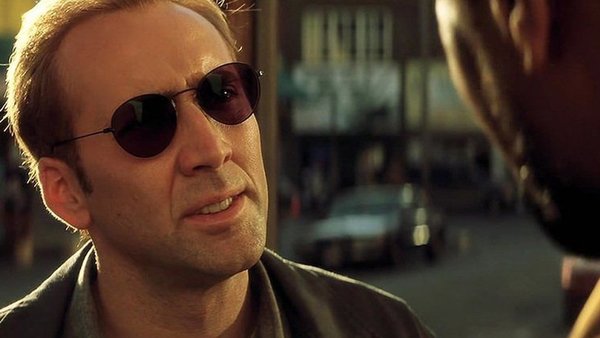

Using the example of Gone in 60 Seconds - a Disney produced car-crime caper which starred Nicolas Cage and Angelina Jolie - Epstein described how, even though the film was considered a success by then CEO Michael Eisner, grossing $242 million against an $103 million budget, according to Disney's own profit statements, that gross was swallowed up by a number of different costs.

As Epstein explains, theatres reportedly kept $129.8 million, and remitted to Disney $101.6 million. $67.4 million went to advertising costs, which when combined with logistics costs and other expenses, apparently brought the total gross profit to $11 million. This apparently led to the movie being $90 million in the red - meaning it has now made a loss. Home media sales and TV residuals apparently do not make up for this either, leading to Gone in 60 Seconds somehow making a $212 million loss, despite a portion of those losses essentially being fabricated, as it's essentially just money the studio has charged to itself.

This is because each movie gets set up as its own company by the studio that is making. That company then pays fees to the company that is already producing the film to begin with. The biggest of these fees is the distribution fee, which tends to be "30-35%" of any sale on that film, be it physical media, streaming, TV showings, or merchandise.

This also creates illusory income - actors receive contracts that include an up-front payment but also payments contingent on net profit. As the hosts of Planet Money describe, an actor's contract may be worth $10 million, but most of that could be comprised of net profits that will never materialise. Epstein argues this is done to guard actor, director, and producer contracts and for agents to protect their value by hiding their up-front salary, but the other consequence is that creatives are denied money they had reason to believe would be theirs, but that the studio never had any intention of paying.