Debunking The WrestleMania Curse

A detailed and timely look at a curious modern phenomenon...

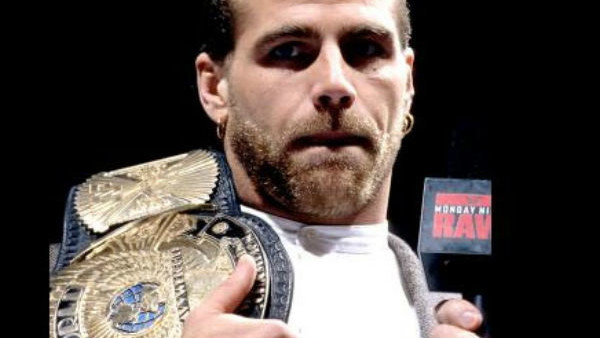

On Thursday, February 13, 1997, Shawn Michaels removed himself from the WWF Heavyweight Title picture ahead of WrestleMania 13. It inconvenienced Vince McMahon, who had to scramble to rearrange the card, but the timing was rather convenient for Michaels. The Showstopper stopped the show as originally planned because - to be both reductive and cynical - he exaggerated the effects of a knee injury to excuse himself from dropping the strap.

The subsequent “curse” of WrestleMania originated as a work - but a series of divergent factors have rendered it a shoot. The Reality Era, indeed.

Steve Austin’s neck injury, which finally caught up with him in November 1999 after two years of modified in-ring work, wasn’t so much the hex of a voodoo priest but the grim march of father time. He was on that borrowed time ever since Owen Hart spiked him into the ground at SummerSlam 1997. His absence indirectly contributed to the hedged betting and megalomania that was the McMahon In Every Corner Fatal 4-Way main event between The Rock, Triple H, The Big Show and Mick Foley at WrestleMania 2000. Thrust into free fall as a result of Austin’s injury and the lack of faith placed in Chris Jericho, that were was just one singles “match” on the card - a Catfight pitting non-wrestlers Terri Runnels and The Kat against one another - underlined the extent to which the havoc one fallen domino can cause. That havoc lay dormant, looming in the background.

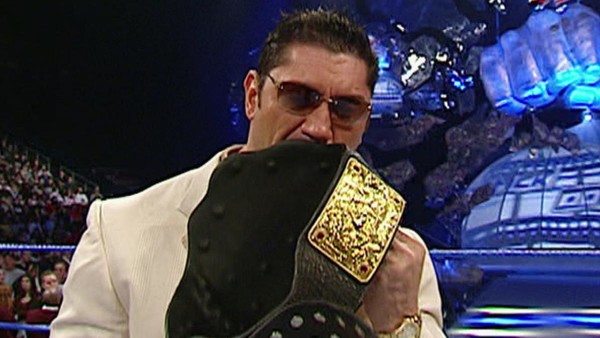

The so-called curse reared its head in 2006, when the planned Batista Vs. Randy Orton World Heavyweight Title match was put on ice alongside the stripped champion’s torn triceps. Batista fell victim to what he later cited as carelessness on the part of Mark Henry on a January 6 house show. Cynics might proffer that an injury arising from a botched sequence between two behemoths, promoted at a rate which betrayed their slow development, wasn’t a curse but rather a grim inevitability.

Understandable surgical intervention and a freak aberration aside, WrestleMania has occurred largely without incident. It was, and is, the biggest night on the wrestling calendar. In years gone by, there was no Wellness Policy in place. There was far greater scope for talents to work hurt, and far less legal risk to allow them to do so. The post-painkiller era has coincided with the rise of the content-heavy approach to in-ring work. Talents feel ever more compelled to get their sh*t in at a time in which regulation dictates they must have their sh*t together. These opposing forces are creating a polarity - one which has, in recent years, caused WrestleMania season to go south.

Time caught up with WWE in spectacular fashion in the months leading up to 2016’s WrestleMania 32. The company had relied on the two-headed monster of Randy Orton and John Cena for near enough a decade. Both men were absent from Dallas. Orton was struck down with his umpteenth shoulder injury, his years-long tragic flaw, in October. Cena, even more so than Orton, was promoted as something even bigger than a hero. He was unbeatable. He had no such flaw - or so it seemed. After an often numbing decade, Cena also suffered a debilitating shoulder injury for which he underwent surgery on January 7. There was no rushed, super-heroic comeback. Cena was human after all. His mooted dream ‘Mania match with the Undertaker was off. Neither man worked a particularly dangerous style - widespread fan rejection of it gave way to the style which succeeded them - but the years of toil, of wrestling frequent, lengthy matches, caught up to them regardless. Cena, Orton, Cesaro, Nikki Bella, Luke Harper and Neville all returned once the dust settled in Dallas. Daniel Bryan did not.

There was also the curious case of Seth Rollins, who also missed his big payday match with Triple H. Though atypically excellent - a man as slight as Rollins did not get where he is in WWE because he isn’t - he is nonetheless typical of the modern wrestling prototype. His matches are crammed full of risky content. That, in the absence of innate charisma and effortless showmanship, is what makes his act so popular. It is what is expected and demanded from him, but it evidently comes at a cost. Is he an unsafe worker? The evidence is piling high enough to make it look beyond that inconvenient truth.

Rollins busted John Cena’s nose open with an errant knee in the summer of 2015. Just months later, he retired Sting after his Buckle Bomb manoeuvre went awry. That same move put paid to what was scheduled to be Finn Bálor’s lengthy Universal Title reign following SummerSlam 2016. Rollins, as we witnessed last week, is also prone to injuring himself. Conventional wisdom states that he was in the wrong position to take Samoa Joe’s Coquina Clutch on the January 30 RAW, during which he reinsured his rebuilt knee. For the second year in a row, his scheduled ‘Mania match opposite Triple H was incredibly close to being called off.

That knee was first injured when the then-WWE Heavyweight Champion tore the ACL, MCL and medial meniscus upon attempting to deliver a sunset flip powerbomb to Kane on a November 4 house show. It was a ridiculous move, in hindsight. He attempted to manoeuvre the far bigger Kane as if he was of at least equal size.

In a way, it reflected the war for the heart of WWE. Rollins was expected to both careen through the ropes to appease his masters in the crowd, and create the illusion of strength to appease his master in the back. There was no curse, no hex; his knee was simply ripped apart by opposing forces.

Worryingly for WWE, there is no clear cure. It cannot rely on the disintegrating old guard. John Cena’s body is at last showing signs of giving up. No t-shirt can conceal that fact. To underscore just how old these men are, the Undertaker needs a new hip. Hip replacement is elective surgery offered to the elderly so that they can enjoy greater mobility in later life. Those who receive it aren’t meant to take bumps or smash themselves through tables.

WWE has been left with a fleet of headliners occupying an unenviable spectrum. On one side lies the old guard, shattered or close enough to it. On the other lies the next generation, Gods driven by the tragic flaw of crowd appeasement. This new generation cannot slow down. Expectations have been set. They have to be “awesome”. They have to satisfy the incessant clamour for high octane demand.

There is one solution. The fabled offseason many fans would welcome - to savour the work of their heroes, if nothing else, in an age where even the most divided fandom can agree there is far too much wrestling - is the only way to reconcile these opposing forces. But the machine must rumble on. And, until it doesn’t, body parts will continue to get caught in its cogs.