The Secret History Behind WWE's Attitude Era

A quick word on the New Generation, by the way.

If you glibly criticise it out-of-hand as a good-for-nothing period of time, you simply weren't there. Purists and/or mid-90s WWE survivors won't tell you that the gimmicks and characters were at their most credible nor that the top slate of stars were the ones to attract massive audiences, but a spirit of experimentation within the inner workings of the World Wrestling Federation in particular has done much to elevate the mindset in retrospect. Time and nostalgia are kind to most things, but people won't be as generous to the post-Attitude Era "Ruthless Aggression" slump years as they are to Bret Hart and Shawn Michaels tearing up the old rules on what made good matches in WWE. They won't ruminate as fondly on Raw's risible Guest Host run as they will WCW's The Diamond Studd and Vinnie Vegas finding their voices as Razor Ramon and Diesel and crossing back over to transform the industry. Name five mid-2000s midcarders. Are they as talented or as memorable as Owen Hart, The 1-2-3 Kid, Jeff Jarrett or Goldust? It took The Undertaker over a decade to rediscover the form he had in 1996 against Mankind.

All of that's to say that while much of it was terrible and all of it evidently wasn't going to turn WWE's ailing fortunes around, the light it did occasionally provide was set to full beam rather than flicker.

Never was this more the case in 1997, than when the aforementioned Raw Is War transformation became the beginning of the end for that blue and yellow logo and a family-friendly veneer that had been dissolving with each passing week. Foundations for change were laid a year earlier by the likes of Stone Cold Steve Austin and Brian Pillman on the weekend shows, with the New Generation starting to feel itself but the New World Order relegating it to Number Two. And foundations for all of that - everything the mainstream North American scene would see play out over the following six years - were planted yet another year earlier.

November 20th 1995 was a show so entrenched in its own time that the WWE Champion wasn't even just referred to as that, but as "the leader of the New Generation". Two men had worn both labels proudly, but 24 hours removed from Diesel dropping the industry's richest prize back to Bret Hart, Kevin Nash was about to disavow everything that had, for 12 months, defined him. Without knowledge of the bombshell soon to drop, it looked on paper like it would be any other edition of the flailing flagship. Opening with a SummerSlam workrate rematch between The Kid and Hakushi and closing with Shawn Michaels Vs Owen Hart, the in-ring quality was assured as normal, but philosophical changes were happening behind the scenes in a way that transformed the outward perceptions of both Vinces - McMahon and Russo - forever. McMahon was identified for who he actually was rather than for what he purported to be. Meanwhile, Russo's ethos was everywhere to be found. It was a night that shifted focus for the company so sharply that the aforementioned publication sporting the Raw branding was soon needed to define the clear difference between the intended energy on Mondays and everywhere else within planet WWE. The very magazine that McMahon used as a full style guide for his rebrand two years later.

The defining moments of the show centred around the two figures that had defined the year for better and worse. Diesel and Shawn Michaels had been in and around the main event all year, first as rivals and then as partners during 'Big Daddy Cool's year with the WWE Championship and later as Tag Team Champions during Michaels' own final run with Intercontinental gold. "The chaps with all the straps" was an on-screen nickname they'd used, but it went some way to needling the bulk of a roster that didn't much care for the pair, their "Kliq" of friends, and just about everything else that sucked about working for WWE at the time. Other than holding on to the top spots, Diesel and Michaels rationalised their power and placement by claiming an obsession with making the business better. Objectively they were failing and failing hard to look at the gate receipts in the single worst financial year for the company in its decades-long history, but they knew in their hearts and minds that the visions they saw for the future of the industry didn't exactly match up with the pirates and ninjas and dentists populating the roster. That's why they funnelled those gimmicks to Bret Hart and pinballed around with the best of the rest until they figured it all out. Ironically, from all their politicking, it was two heavy defeats rather than glorious victories that triggered the transformational moments on the November 20th Raw.

More than a little sore that he'd been outfought and out-thought by Bret Hart one night prior, former Champion Diesel was spotted barging people out of the way as he arrived backstage, stopping only to speak with Shawn Michaels before marching out midway through Savio Vega's match with Skip. Minutes earlier, forgotten company merch shill Barry Didinsky was flogging denim jackets with Diesel's face airbrushed up the back. But 'BDC' wasn't sporting the merch, nor the grin he had literally painted on. Wearing a leather jacket and a scowl, he piefaced Skip, beckoned Vega to bail, and grabbed the microphone. Never once stepping into the ring, he cut a promo his neutered babyface run hadn't permitted him to for a year. And he cut it right in front of - and to - the man that had caused that.

Having brutalised Bret after the bell the night before, Diesel refused to apologise. Instead, he doubled down and suggested more was in store for anybody he deemed worthy of the beating, no longer content to smile and nod and be McMahon's corporate puppet. The work and shoot overlapped and intersected in a captivating fashion, particularly in the acknowledgement of McMahon as the out-and-out string-puller in WWE years before they'd abandon the "President" title given to Gorilla Monsoon. It was a fascinating new spin on the Diesel gimmick, and it was rooted in truth - it had been a bad year for business in spite of a lot of people's best efforts, and the poor creative afforded to the Champion did nothing to help his performance in the spot. Ever the businessman, Kevin Nash turned on the fans while making sure they bought his merch, promising to still slap fives and bump fists as long as the hand was adorned by the black Diesel glove. This was more than just a nice sales stunt though - this was WWE and Nash himself allowing fans to decide if they liked him or not and follow that emotion rather than having the storylines or gimmick dictate the mood. In a further illustration of the point, Diesel confirmed he was still good buddies with Shawn Michaels, the company's undisputed next top babyface star. They'd square that circle in the storylines later on down the road, but in the moment it was yet another case of the audience being given the option to exert some control and the wrestlers being encouraged to bounce off of that for their own long-term benefit. These were Russo principles in print making it to screen, these were wrestler instincts being closer to pop culture than Vince McMahon, and these were gestures to the fans that rebuilt bridges that the masses would eventually cross. These were indicators of changing attitudes towards how to book characters credibly, and by the end of this edition of Raw, they weren't even the biggest ones.

Shawn Michaels has ostensibly experienced the biggest setback he'd encounter on the long road to a certain WrestleMania XII title win a month or so before this Raw when he was injured in the now-infamous Syracuse bar fight. He surrendered his Intercontinental Championship and approximately a month of paydays before returning at the Survivor Series with an electrifying win for his team. Working a "Wild Card" match that mixed heels and babyfaces together in yet another worthy experiment for the time, Michaels was put down with separate powerbombs by Razor Ramon and Sid and leg dropped by Yokozuna, all as the commentators wondered aloud if he was fully recovered upstairs. After sealing the win alongside Ahmed Johnson, the answer to that seemed to be Yes.

But a more creatively energised WWE was about to change the question.

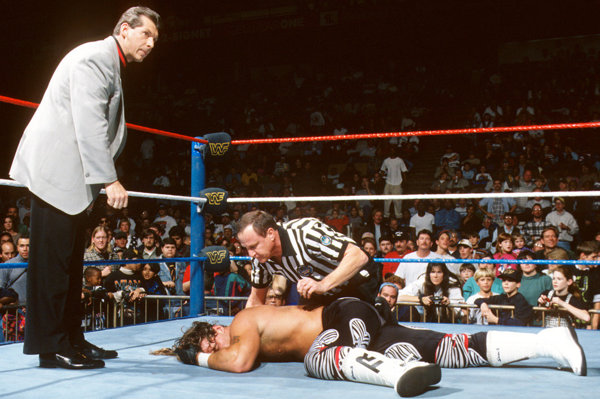

The same hyped-up Michaels appeared, black gloves and all, one night later in the main event of Raw against Owen Hart in a match that seemingly existed to kick off his Royal Rumble build. It did just that, but in a way few anticipated. After the usual high-intensity contest between the pair, Michaels started selling minor head issues after repeated shots to his head, neck and face. It was, in retrospect, elegant selling from Michaels, but it doesn't look out of the ordinary on first viewing. He goes on to fire back from suffering a brutal enzuigiri, mounting the comeback as he often would with a clothesline to the floor followed by skinning the cat back inside to add insult to injury. Only this time, it's clearly him that's hurt. As the crowd go wild, Michaels clutches his head and hits the deck. It brings the commentary to a stop, a ringside fan front row removes the camera from their face and looks on in shock, and everybody else gradually comes around to the idea that the fallen babyface could be in real trouble. As Owen, Jim Cornette and Mr Fuji leave the scene, the sight of a downed Michaels in all we're left with for the remaining four minutes of the broadcast. It's quiet, it's tense, it's real-feeling, and it's what little of neon-90s WWE was known for. Vince McMahon drops the headset to enter the ring, as the show fades to commercial. When it returns, the ring is filled with medical professionals and officials, and the only sounds to be heard are from speculating fans and the mumblings of McMahon and the medics in the ring. It's taking time and effort and even Jerry Lawler is looking to Vince for guidance as everybody scrambles. One final commercial break brings viewers back to the sights of fans in tears and Michaels having an oxygen mask applied as doctors do at least confirm he's conscious before the show ominously goes off the air.

Unflinching when watched in the present day, it's outright remarkable that it played out the way it did all the way back then. Blurring the lines for the second time in one show, and with a character central to both examples, it was subtly informing you who to care most about amongst the cavalcade of circus gimmicks, and asking the audience for an emotional buy-in in a way that hadn't really been explored since the bubble burst several years earlier. It'd be bastardised of course, in much the same way talk of the "corporate suits" would, but on this night, Diesel and Shawn's on-the-road bluster made for big business. Though the times ahead were a long way removed from the real turnaround in 1998, gates at house shows in early 1996 were strong again, as was the encouraging buyrate for the Royal Rumble sold almost entirely on 'HBK's impossible comeback. Madison Square Garden drew well again for shows on either side of WrestleMania XII, even if the continued pushes for The Kliq resulted in two loaded weapons being handed to the opposition. Nash and Scott Hall jumping to WCW resulted in the New World Order forming and crushing just about everything WWE attempted in response for well over a year. But the seeds for the tonal shift the industry needed to take were sown here.

What of Stone Cold Steve Austin here though? It seems so odd and almost unfair that figure so integral in 1996 and 1997 just wasn't quite through the door in time in 1995 for being part of such a transformational night in the history of the organisation.

Or was he?

(CONT'D)