Why You Will Never Watch The Truman Show The Same Way Again

Why The Truman Show Is More Important Than You Realise

Have you ever felt like the star of your own staged reality show? That everyone around you is playing a role in a world of fabrication and keeping you out of the secret? And that everywhere you go, your every action is being monitored by cameras? These are symptoms commonly associated with the delusion ‘Truman syndrome’, which takes its name from the film of the same name.

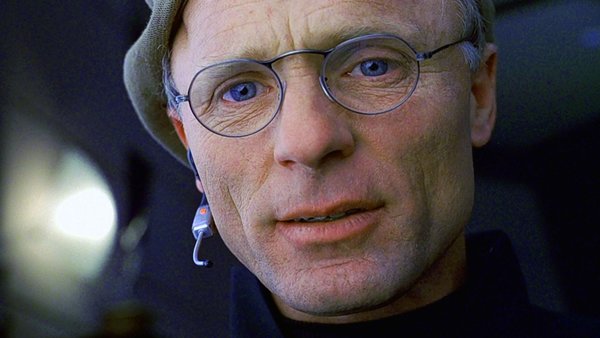

The Truman Show follows Truman Burbank played by Jim Carrey, the star of the reality television show, The Truman Show. To Truman, his life in Seahaven is normal. The one difference? Everyone is aware that they are part of a television show - everyone except Truman. Every person around him is an actor who works under the direction of creator Christof (Ed Harris). The movie is an allegory to Plato’s Cave in that Truman makes his reality from what is shown to him - he has no reason to question anything as he has never known anything different.

That is, until, he does.

The Truman Show poses questions, ideas, and themes which are just as important today as they were in 1998. Our quest for truth comes when significant moments happen that destabilise our expectations, displacing the reality of what we once knew and therefore pushing us to discover the reality of a given matter.

And who hasn’t had a moment of existential crisis in which we question our autonomy? Are we truly the narrators of our own lives if everything has been chosen for us? If the actions we make are ours, but the environment we exist in is designed and controlled by others, then how free are we? Just how does an individual take back control of their life after living for so long without that footing? And, more importantly, what does that control even look like?

Of course, these hefty existential questions may not have been at the forefront of your mind when watching The Truman Show for the first time. However, when rewatching with a current-day perspective, the questions that Weir’s film asks become evermore urgent. So much has changed in the two decades since Truman escaped Seahaven, and it recontextualises the viewing experience in key ways.