The Impossible End Of Wrestling’s Worst Era

In retrospect, it was remarkable that Punk was permitted to retain his own gimmick. It took him years to reach a level below John Cena’s pinnacle. He was not blameless - his endless would-be breakthrough programme with John Morrison was plagued with multiple nothing matches - but it was primarily the fault of WWE that he was made to get over on his own accord. He was a superstar in 2009, but he wasn’t meant to be. Across 2010, as the leader of the Straight Edge Society, Punk starred as the generational heel he was before he even worked a WWE dark match. In 2011, he cut the infamous Pipe Bomb promo. In it, he articulated that which many fans felt after this constant stream of halfhearted flirtations with good, productive fan-forward wrestling. And through it, Punk widened the chasm between WWE and the audience to what, ultimately, was an irreconcilable extent. There were two WWEs.

There was the WWE that appealed to the young children it targeted through the push of John Cena, and there was the WWE that millennial fans suffered because they believed in CM Punk and wanted to watch something that was big time. WWE could have enjoyed the benefits of these two audiences and, for a few years, they almost did - but not before a short decade of an abysmal philosophy of talent recruitment.

WWE did not sign Samoa Joe from Ring Of Honor because they had created their own pool of talent from which to recruit.

The developmental system was a joke that was much too successful too early.

The vaunted Ohio Valley Wrestling Class of 2002 was an impossible aberration. Brock Lesnar was a once-in-a-lifetime athlete so freakish that he later dominated the UFC with relatively minimal training because he was such an eye-catching beast of a human being. John Cena was simply a megastar who happened to choose wrestling as his profession and was one of the rare few who was able to move past it. He later joined Batista, who was a more understated but no less effective badass, in Hollywood. Randy Orton was never a needle-mover - would wrestling look any different had he not entered it? - but was a super-reliable and gifted natural who ultimately showed his star and staying power as much as WWE insisted upon it.

WWE must have thought this developing greenhorns lark was easy, hence why they essentially just expected it to happen all over again. That would explain why they treated OVW and its creative force Jim Cornette with contempt - and then, when Cornette was fired for slapping Santino Marella, why WWE thought it was as easy as setting up regional throwback territories in Atlanta and Tampa. The latter was far more productive than the former - Deep South Wrestling was more a small man’s outlet for torture than a wrestling school - but Florida Championship Wrestling, helmed by the overlooked, brilliant wrestling mind Tom Prichard, was hardly fit for purpose. Roman Reigns and Big E, amongst others, learned the trade in a facility that for months had no running water, but while they eventually ascended to the top of the card, neither entered the WWE system as an experienced, good-to-go game-changer.

OVW, DSW, FCW: over-delivery, laughable dumpster fire, very modest success. Fundamentally, wherever it was located, the satellite feeder system did not work. WWE preferred to recruit mostly very large men - and telegenic female models - with zero or minimal experience. Chris Jericho, back when he was sharper, once remarked on his podcast that Vince believes “If you came from another company, it didn’t count” and that Vince does not like it when he is not in control of a performer’s success. Thus, appalled by the idea that there was such a thing as ‘Ring Of Honor’ in which wrestlers outside of the WWE system were received in niche circles as demigods, he essentially signed camera-friendly lumps of clay, to draw on Minoru Suzuki’s infamous analogy of the WWE system. Even the best trainers - and Tom Prichard was that - could not prevent the inevitable. The same coaching philosophy and the same drills and the same curriculum will result in the same wrestlers.

Forget the Undertaker’s parlour tricks. Forget Kota Ibushi entering, with eerily blank eyes, a sort of fugue state in which he can’t feel pain and thrusts sickening jabs into the throats of his opponents. Forget the bone-chilling, quiet delivery of Jake ‘The Snake’ Roberts. Forget New Jack taking leave of his senses and mauling a hapless, terrified opponent for real.

The most horrifying sight in pro wrestling history is that of the WWE HD logo appearing in the top-right corner of your screen as a midcard TV match happened between 2008-2011. At that point, the folly of the developmental system had fully materialised. WWE was in the cookie cutter era. So many bland matches, featuring mechanically identical talents scared of doing something to get themselves over, simply…happened.

The developmental era of WWE was atrocious, almost comically so. For much of the 2000s, the biggest worm of all-time, John Laurinaitis, oversaw the programme. When he wasn’t signing synthetic, wildly unqualified wrestlers on a physique-first basis, John Laurinaitis, infamously, was signing the wrong one-legged wrestler. WWE was a joke so outrageous that an animated sitcom writer wouldn’t get away with pitching it. Nobody is that stupid.

In the wake of Chris Benoit killing his wife Nancy, child Daniel and himself in 2007, WWE cynically abandoned, at long last, the grim pursuit of controversy-baiting schlock. In its place, in order to position itself as clean sponsor-friendly family fun - a savvy move launched by Stephanie McMahon, who probably drew more money to WWE than most - the promotion’s storylines became unfunny, trivial, cringe-worthy. PG WWE, led by John Cena, was a level significantly below the best children’s television. To that jaded millennial audience, Cena was an insufferable gurning clown. Vince always wanted his sports entertainers to be living action figures; John Cena, clunky and unable to convey genuine emotion, was the closest he ever came to that ideal.

WWE was not wall-to-wall diabolical as the 2000s receded from view. Certain top-level programmes peaked at outstanding: the well-plotted blood feud between Chris Jericho and Shawn Michaels; the Undertaker’s Streak and the ‘End of an Era’ story-within-a-story; CM Punk rising to superstardom as Jeff Hardy proved to be the ideal vehicle with which to reboot his sanctimonious better-than-you persona…

This actually good storytelling was the absolute least fans could reasonably expect from what, by that point, was the most comfortably moneyed pro wrestling outfit in history. More often than not - statistically - those fans watched Cena, Orton and Triple H wrestle one another in various combinations for two full years.

Developmental, post-OVW, even at its most productive, was just a glorified wrestling school. These talents could have trained anywhere else. WWE, in the meantime, rarely recruited from what, towards the end of the 2010s, had become a bonafide scene: the super-indie circuit.

In the early-to-mid 2000s, Ring Of Honor captured a comparatively tiny but influential share of the wrestling market. Aghast at the bland and puerile state of the monopoly, those few who held an interest in great in-ring wrestling followed ROH through its DVD releases. ROH was AEW before AEW: with its puroresu-inspired narrative framework, it was the antidote to WWE’s trite, frivolous “entertainment”.

The early stars of Ring Of Honor became legends. CM Punk, a loathsome, pious megalomaniac, was so effective at drawing heat, with his punchy, venomous, cocksure delivery, that he was in effect a time traveller. He generated reactions thought lost in a more knowing, detached modern era. Joe, as mentioned, was revered on the level of the ‘90s All Japan gods. Bryan Danielson was the greatest wrestler alive, a man so incredible at pacing the struggle of a violent wrestling match that it was practically impossible not to rate him. At a stretch, you could argue that he was a bit indulgent on occasion. Otherwise, the American Dragon was the objectively great genius in a subjective medium. AJ Styles continued to redefine the athletic standard - tighter, more ambitious, more exhilarating than the WCW cruiserweights who forged the path through which he sprinted. Backed by wrestlers who reintroduced a degree of authenticity not witnessed since the pomp of ECW (Homicide) and great stooge heels without whom it would have all been too much (Jimmy Rave), ROH was the Best In The World.

As with everything else, particularly the ceaseless pro wrestling churn, ROH eventually did become too much. Davey Richards epitomised this descent into parody; his matches would have been dumb, stiff, intense fun, had he not been in there for what felt like an eternity.

Over on the west coast, Pro Wrestling Guerrilla supplanted ROH as the preeminent hipster league. As co-founder Scott Lost put it, PWG wanted to be ROH - “without the stick in its ass”. Much of the promotion’s early output, with its awful edgelord racism, has dated horrendously, but peak PWG was an exhilarating, irreverent battleground - an intense competition in which the goal was to get over and appease the discerning tastemakers that crammed inside the sweltering dump that was the American Legion Hall in Reseda, California.

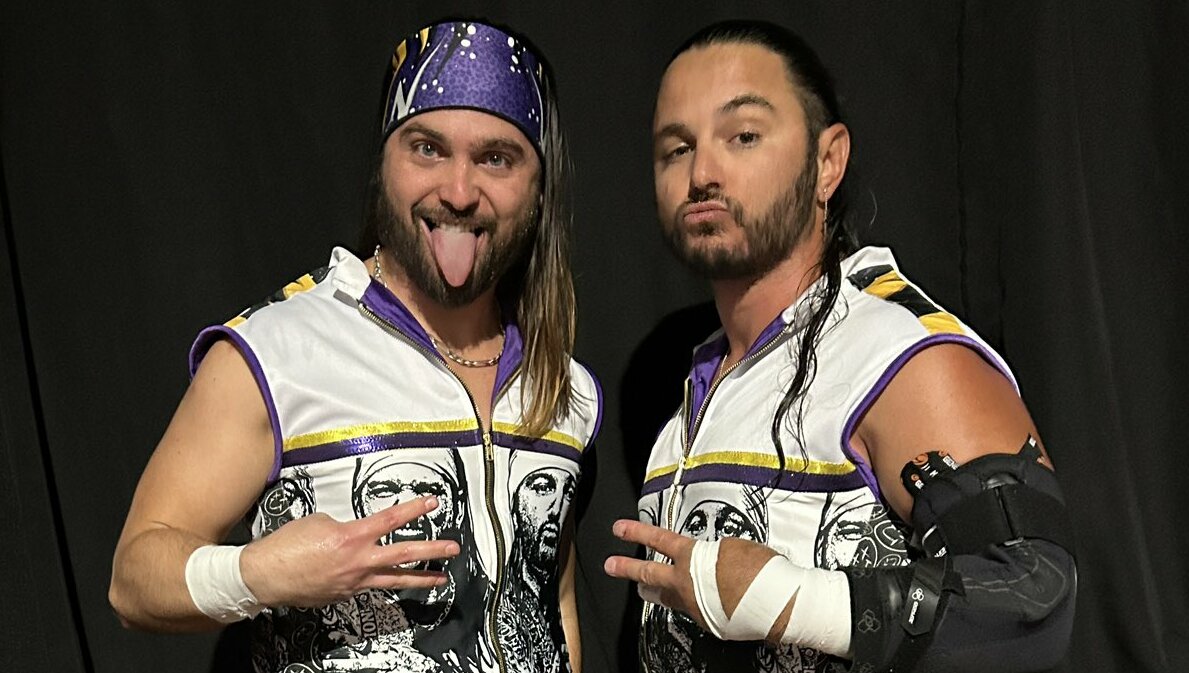

PWG was the place in which the crowd, after ironically taking to their hand-slapping Hardy Boyz update and Hanson theme song initially, roared in approval as the Young Bucks were mutilated by Bryan Danielson and Roderick Strong in 2009. Booker Super Dragon wanted the beating to feel so awful that the crowd eventually sympathised with the Bucks. It didn’t happen. Strong and Danielson intensified the rampage. At one point, Danielson accidentally kicked Matt Jackson square in the face. Matt had just eaten a forearm to the jaw so vicious that he involuntarily slumped out of position.

If anything, the crowd was so unforgiving that Strong and Danielson turned babyface several times over. When the Bucks won, following an unconvincing and anticlimactic closing stretch, they were booed out of the building.

It was only when the Bucks learned this painful lesson and pissed the crowd off in response months later - brilliantly, by redoing the exact same spot when met with chants of “Same old s**8!” - that the bloodlust was quenched amongst the crowd. Contrary to the daft idea that the PWG crowd would pop at any old high spot, the opposite was true.

A few years removed from that match, the Bucks, in the process of mastering that craft, wrestled the Super Smash Bros. and Adam Cole and Kyle O’Reilly at Threemendous III on July 21, 2012 in a three-way ladder match. It was one of the most insane spectacles ever promoted in a North American wrestling ring. In it, Nick Jackson tweaked a genre standard spot. He climbed the ladder in a bid to retrieve the Tag Team titles. Evil Uno threatened to topple him over. Nick feigned a dramatic tumble to the outside, but, in a magnificent twist, a moment of crazed inspiration, used the top rope as a springboard to launch a senton that flattened the field of wrestlers below. The Reseda crow lost their goddamn minds. Contrast that with WWE developmental wrestlers grabbing holds and executing a standard, imposed layout in accordance with the in-house style. It’s little wonder that one generation of wrestlers truly learned how to get over.

(In a notable irony, given that the Young Bucks didn’t know how to work and WWE don’t do spot-fests, Sin Cara replicated that spot during the Money In The Bank Ladder match at WrestleMania 32. Ricochet also executed the exact same sequence nine full years later at WWE Money In The Bank 2021.)

Unlike Florida Championship Wrestling, real, discerning fans filed into the Legion. If those fans didn’t give the Bucks such a hard time, Nick Jackson might not have thought to do that spot. He was determined to prove that he was one step ahead of the smug know-it-alls in attendance.

On a broader level, he might not have been driven to impress through a level of creative expression that was encouraged by the promoter. And, since every other trendy import was intent on getting over and making their name, a sense of cutthroat competition emerged. A wrestler had to earn that spot. They didn’t get it just because they had a certain look and were groomed for it.

In PWG, the wrestlers often performed guest commentary. It was mostly daft, knockabout fun in the vein of the promotion’s culture - but it served a dual purpose. If a wrestler popped at something, it meant more. Conversely, and wrestlers improved on the back of this, if one of their peers messed up in some way, the guest commentator would bury them mercilessly. In a PWG classic, Matt Sydal, Ricochet and Will Ospreay defeated Adam Cole and the Young Bucks. In it, after wowing the crowd with a high spot, Ospreay sat on the mat and for some reason gave them a thumbs up with a deeply regrettable goofy expression on his face. Giddy with adulation, Ospreay sort of crossed his eyes and stuck his tongue out. Chuck Taylor was on commentary and said that Ospreay looked “like a d*ckhead”. Ospreay remains very theatrical with his facial expressions, but he was never quite so cringe-worthy after that harsh (but thoroughly justified) burial. Bad habits were either bullied or literally stamped out of the wrestlers.

Yes, the infamous invisible grenade spot was also very stupid, but PWG was lawless terrain. The wrestlers were encouraged to piss about and determine what worked, what worked but wasn’t worth doing again, what didn’t work whatsoever. PWG was the rough demo every artist must record before nailing their sound; FCW was WWE’s soulless attempt to ghost-write something manufactured.

PWG was the last true territory. Wrestlers got over there. Wrestlers were made there. Not funded by WWE, it became, in effect and alongside ROH, its most effective developmental territory.

In one of the endless incredible gags in the peak era of ‘The Simpsons’, the titular family, tormented by villain Sideshow Bob, is forced into the Witness Protection programme in season five episode ‘Cape Feare’. As part of the programme, they must naturally change their surnames. Homer, a perfect idiot, is unable to grasp this. He maintains that he understands. The FBI agents tell him that his new name is Mr. Thompson, but when they address him as ‘Mr. Thompson’, he doesn’t respond. His name is Homer Simpson. In the final punchline, one of the exasperated agents, his tie loosened to convey the frustration and the long passing of time, says “Now, when I say “Hello Mr. Thompson” and press down on your foot, you smile and nod”. He stamps on Homer’s foot and says “Hello, Mr. Thompson”. Homer doesn’t get it. Who’s Mr Thompson? He’s Homer Simpson. Homer whispers to the other agent “I think he’s talking to you”.

This scene, designed to portray the dumbest human being on the planet, is almost precisely analogous to the relationship between Vince McMahon and the more cynical “vocal minority” of the WWE fanbase. They told Vince - time and time again, by jeering John Cena or chanting for CM Punk or simply tuning out of the product - that they wanted to see a wrestling-forward product featuring state-of-the-art wrestlers that they liked no matter how relatively small or pale they were. They in effect stamped on Vince’s foot over and over again. “I think they want large sports entertainers,” Vince said, before, to draw on one of countless examples, handing Daniel Bryan’s “Yes!” chant to the Big Show under the belief that Show was bigger and thus automatically better.

Vince was slightly less stupid than Homer Simpson. He at least knew that many of you really rather liked Daniel Bryan; he just couldn't care less. Moreover, Vince also knew that nobody else could monetise this demand on a financially viable scale. That would change - but it might not have, had Vince responded to karma’s call.

He was kicked in the foot yet again on the road to WrestleMania XXX. He tried to sideline Daniel Bryan in place of Batista, who was by that point just the latest part-time star who had understood that they could return for a less intensive January to April schedule (a trend that only lowered the ceiling on the hapless full-time main roster). Bryan of course got over, and how, through his expert in-ring work and his ability to rig the system with his simple, ingenious use of crowd interaction; before there was “Yeet”, there was “Yes!”

CONT'D...