The Impossible End Of Wrestling’s Worst Era

The modern era of New Japan Pro Wrestling - this isn’t a strict consensus, there never is - peaked between 2012 and 2019. Great as NXT was, it wasn’t great enough to thwart the rise of the resurgence era.

Hiroshi Tanahashi was a genius who could get more out of a well-timed dragon screw - he did it in every match and it would always make perfect sense and you’d still never, ever expect it - than a thousand other wrestlers would get out of a more spectacular move. Kazuchika Okada, the Ace who supplanted him, was the best-ever version of the invincible champion. He paced his matches to make his opponent’s comeback feel earned better than any of his contemporaries and predecessors. Tetsuya Naito was a sick, cool, aloof freak who was incredible at revealing that he did have heart after all (he also perfected the exhilarating danger inherent to pro wrestling). Shinsuke Nakamura was almost the perfect wrestler at his peak. He boasted megastar charisma and a super-credible, unique strike-based arsenal. He was a deranged composite of everything that was ever great. Underneath, Tomohiro Ishii was a man who every single time could convince you that he was about to die or could never die, often, somehow, in the space of a minute.

The level of quality, combined with the easy access to it in a borderless digital age, saw NJPW become the #2 promotion in the United States. The second audience loved NXT, but it just wasn’t enough anymore.

Everything changed on January 4, 2017.

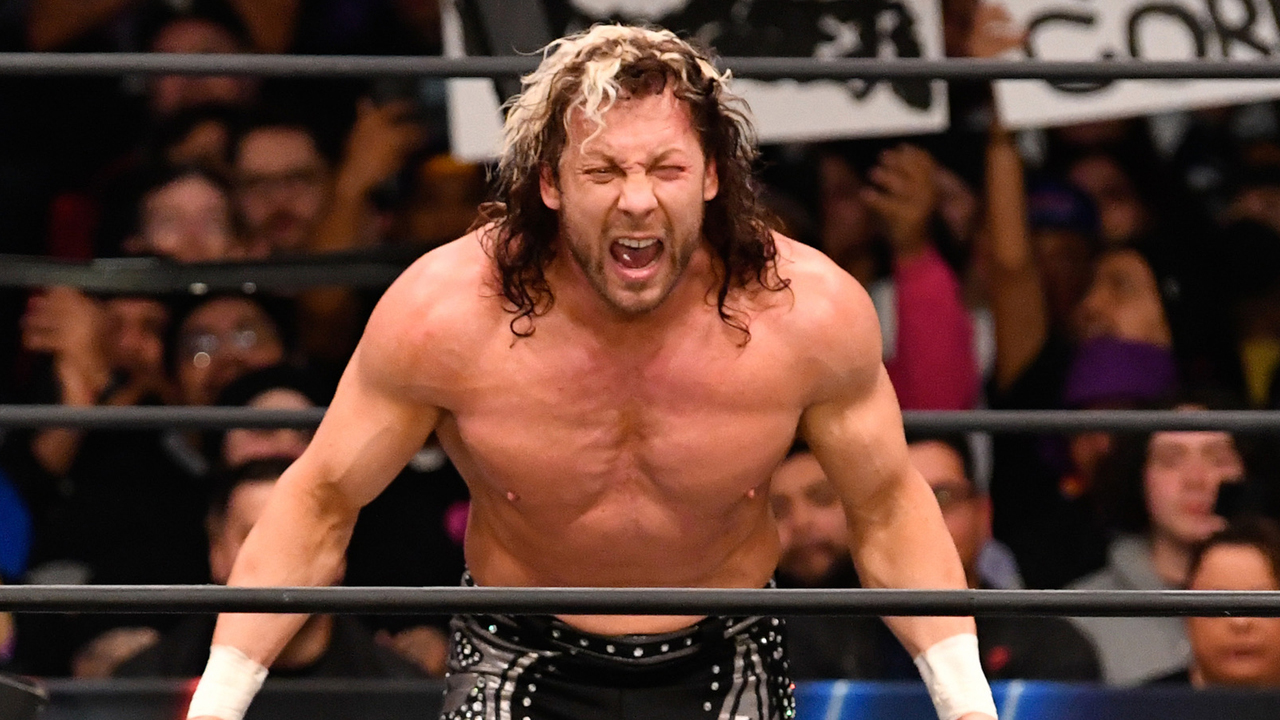

Kenny Omega lost to Kazuchika Okada at the Tokyo Dome, but, as a pro wrestling genius, he got over to a seismic extent in defeat. The match was incredible, quite possibly the greatest ever held. It was so unbelievable that, on commentary, Steve Corino could only make bewildered jock noises as he couldn’t believe he hadn’t just seen the finish. Before the insane closing stretch, so close that every mere strike felt like the finish, Omega transformed into the next best in the world to an even loftier designation. His physical timing was so supernaturally precise that he was probably a centimetre from doing himself significant damage when taking a deranged back body drop bump over the ropes and through a famously sturdy Japanese table. The sound of the Tokyo Dome crowd, when Omega performed a springboard moonsault to the outside, clearing the guardrail, was a rare thing. They reacted like they’d seen some natural wonder. It was the aurora borealis of wrestling spots.

The emotion and drama of that fatigued shoot-out at 40 minutes broke another new barrier of sound. Every fan sounded like they were in a different, very personal state of disbelief. The atmosphere felt overdubbed; it was the total antithesis of the loud but performative, chant-heavy heat you almost invariably hear everywhere else. The first 15 minutes of Okada Vs. Omega 1 planted the idea that wrestling, for the first time since 1998, could be as big and better than WWE. By the time the closing bell sounded, that idea had already bloomed.

Omega Vs. Okada I changed everything in wrestling, even the vernacular. A WWE wrestler would get six stars if their matches took place in the Tokyo Dome.

This match increased the second audience, measurably so; NJPW World subscriptions doubled ahead of it. With Kenny Omega as the top foreign star, a bridge was erected over the pacific ocean. NJPW appealed further to the North American fanbase. NJPW held shows in the States and introduced the United States title to deepen its tendrils into the western market.

NJPW somehow surpassed that unscaled peak over the next two years, commercially and artistically. Okada Vs. Omega IV was the next greatest match of all time. Alpha Vs. Omega - Chris Jericho Vs. Kenny Omega at Wrestle Kingdom 12 - again doubled World subscriptions. That Jericho, a top WWE star, would work for NJPW - where he would never seriously entertain the idea of working for TNA/Impact Wrestling - was another indication that something massive, unthinkable, was sparking into life.

Lapsed WWE fans as much as anything hated the WWE creative process. They resented John Cena, were unmoved by the in-house style, and were exhausted by the constant retconning of vaguely promising storylines - but the stilted writing and the idea that these people were artificial and reading from awful scripts could not be shaken.

Being The Elite hasn’t aged particularly well and was wildly uneven at the time. Certain gags were inspired - Cody Rhodes wildly celebrating his win over Kenny Omega at ROH Supercard of Honor 2018 as his wife required urgent medical attention in the very next room, for one - but there was a lot of snark and corniness. The show nonetheless embarrassed WWE’s writing at its peak, not that that was altogether difficult; by the mid-2010s, WWE did a stunningly effective job of humiliating itself.

As silly as much of BTE was, it obviously connected with a great deal of people. The second audience had known for a long time that other companies could promote better in-ring action than WWE (or action that was better suited to their tastes). Storylines, though?

That idea was nothing new. The ROH Vs. Combat Zone Wrestling feud was the hydrogen bomb to the Invasion’s coughing baby. Still, that BTE’s success could drive a 10,000+ attended show was the tipping point.

That a do-it-yourself YouTube show could better engage its (smaller) audience than WWE’s creative process wasn’t just shocking: it was exhilarating. The lapsed second audience knew that WWE’s way of doing things was wrong - certainly, not the only things could be done. All In was proof. All In instilled in those fans a sense of righteous defiance. To be told you were a “mark” who couldn’t grasp what was best for business outside of your niche little forums - only to discover you were in fact correct - was a physical high of validation. The AEW “tribe” existed before AEW.

It’s easy to rubbish Being The Elite in hindsight. Some of it was awful, and at least two cast members have been rightfully scrubbed from the pro wrestling consciousness. But the series told many popular stories, and whether you hated them or can’t bear to watch them back now, on September 1, 2018, the cast of BTE did that which WWE could not or would not do. They sent the fans home happy that they had invested in something with an actual payoff.

BTE drove the resurgence of Ring Of Honor. The aforementioned 2012 Supercard drew a company record of 6,100. Cody Rhodes was a huge draw there, and his rhetoric and conviction was instrumental in the “movement” breaking big.

The landscape was in a state of transformation by 2018. The second audience no longer had to naively dream of, for example, Johnny Gargano headlining WrestleMania. It was never going to happen. If they wanted to see that style on the big stage, they could simply pay to watch Kenny Omega headline Wrestle Kingdom 13.

In 2018, a millennial fan, one of the many that comprised the second audience, took an interest in this new scene. He attended one of the shows NJPW promoted in their bid to expand into the west. His sense that a wrestling alternative could be a viable major cable proposition actually predated All In (although All In did act as proof of concept to the TV industry). That millennial fan was the son of a billionaire named Tony Khan.

As NXT strived for a movement that was organically materialising elsewhere, the main roster plummeted to hitherto unexplored depths of awfulness. Many lapsed fans have their own personal goodbye. It wasn’t just the second audience that Vince McMahon treated with contempt in the late 2010s.

As expertly tracked by Brandon Thurston of Wrestlenomics, the dismal events of the 2015 Royal Rumble accelerated WWE’s decline in viewership. Several internet darlings were ejected from the match, in order to portray the unpopular office favourite Roman Reigns as the lesser of evils, by tedious antiques Kane and the Big Show. Dolph Ziggler et al., hoisted out by the back of their trunks, resembled sentient bags of trash. One picture. One thousand words.

As NJPW courted the second audience in 2017, with Omega hunting down the most well-booked World champion in wrestling, WWE pissed off the primary audience by crowning Jinder Mahal as WWE Heavyweight champion. This was a disastrous, insulting move. This booking decision underscored how utterly meaningless WWE had become. It was one thing, to watch Roman Reigns suffer in the babyface role when he was surely better suited to play heel. WWE barely even attempted to get Jinder over. Mahal was a completely generic in-ring worker with no charisma nor presence. He was a spiritual successor to the infamous late 2000s bore Vladimir Kozlov, but WWE at least tried to legitimise Kozlov with a steady, committed push. Jinder, as low as jobbers get in WWE, simply won the chance to defeat WWE Champion Randy Orton and did so in just over a month. Before winning that Six-Pack Challenge on SmackDown, Jinder lost in three minutes to the lowly Mojo Rawley on April 11, 2017. 40 days later, at Backlash on May 21, he was WWE Champion. At no point throughout this period did his perception change amongst the public. WWE fans viewed this all with a sense of bemusement. They had never mattered less. The WWE Champion was neither good nor over when the absolute minimum requirement was to be both of those things.

NXT fans received yet another reminder of this when they watched Bayley’s main roster run with utter disbelief. Bayley - a superfan who must have missed every other show with a plunder match on it - refused to use a kendo stick against Alexa Bliss at Extreme Rules 2017. This was the wrestler, again, who once crushed the hand of Sasha Banks to exact her revenge.

By 2017, WWE fans had entered a bargaining process with WWE. They were no longer hopeful of watching a smaller, more athletic wrestler in kick pads ascend to the top of the card. That was hopelessly naive - but what about Braun Strowman?

CONT'D...