Wrestling Psychology 101: Everything You Were Too Afraid To Ask

Syntax might be that word. Pro wrestling is the art of the “when”.

Imagine a match. Two wrestlers tie-up. Wrestler Y manages to cinch in a headlock about 10 seconds in. Wrestler X struggles in the hold for all of a few seconds before Wrestler Y hits them with a headlock takeover. Wrestler Y goes for an early pin, just to make Wrestler X exert a little energy by kicking out. Wrestler X waits until 2.99 before kicking out, and when they do, their body flails, they pound the mat, they stand up, kick the bottom rope and appeal to the crowd. This would scan as a mockery of the form.

This hypothetical match is in the wrong order completely. The syntax is off.

Hogan can’t slam André midway through the match. Austin can’t get colour before he takes a beating and keeps getting back up. The death match wrestler doesn’t explode before they teeter suspensefully in close proximity to the barbed wire. Even the Young Bucks can’t get a super-close near-fall before they’ve pissed off the crowd with their bratty, hyperactive body language.

Effective wrestling psychology is all about plotting the story beats and communicating strong body language in the spaces between moves in the correct order. Only when the syntax is correct will the histrionic babyface appeal feel life-affirming. Psychology, syntax, whatever you want to call it: it’s all about earning those moments.

ECW legend Sabu understood and trolled this process at the same time. Known as a spot merchant lacking in psychology in some circles, his use of “syntax” was actually inspired, in a weird way. He once explained to David Bixenspan that he would deliberately bore the audience with mat work - that he wasn’t much good at - in the early phase of his matches. That way, his trademark plunder spots would feel even more spectacular and unhinged (and exciting) in contrast. He very much got the order of when to do what, and as such, his revered body of work is still raved about years and years later.

Oddly, considering the wrestlers could not be more different, this approach isn’t that far removed from that of Roman Reigns. In his Tribal Chief heel persona, the typical Roman match starts off at a glacial pace. The idea is to slowly draw the audience into it so that the limited and familiar range of action set-pieces - the ref bumps, the barricade spots, the near-falls - feels electrifying in the closing stretch. Reigns didn’t do much at his peak. Some believe he did too little. But his domineering presence, smug facials, the gradual sense that he was set to erupt because he couldn’t get it done: it was a main event act for a reason. He was superb at the old staples. Maybe there is a timelessness to it.

Or maybe it’s the attitude of the wrestler who does it.

Eddie Kingston puts everything in the right order, but is so great that his matches never actually feel structured. It never feels like he’s nakedly chasing a Match Of The Year candidate. There’s an impulsive chaos to his work that positions him as the closest disciple to the great Terry Funk. He treats wrestling as a matter of survival. He’s scrappy and he makes mistakes because he’s clever enough to know that you can’t be too perfect. He does not subscribe to the idea that the babyface should be the superior wrestler because that is not him. He knows that authenticity is king.

Syntax is itself a flawed term because it’s too scientific. Craft is vital to psychology, but at the same time, some wrestlers are so magnetic and popular that it doesn’t really matter what order they get their stuff in, or if it looks any good. Sid was cooler and more over than a hundred smooth, solid hands.

Those wrestlers can construct what might resemble a good, dramatic match, with well-placed twists and turns, but lack the presence and charisma to make people care. CM Punk’s awful elbow drop is more effective than a hundred more spectacular high spots because he has it, and they don’t.

Sometimes a dynamic is just pure magic in a way that cannot be explained.

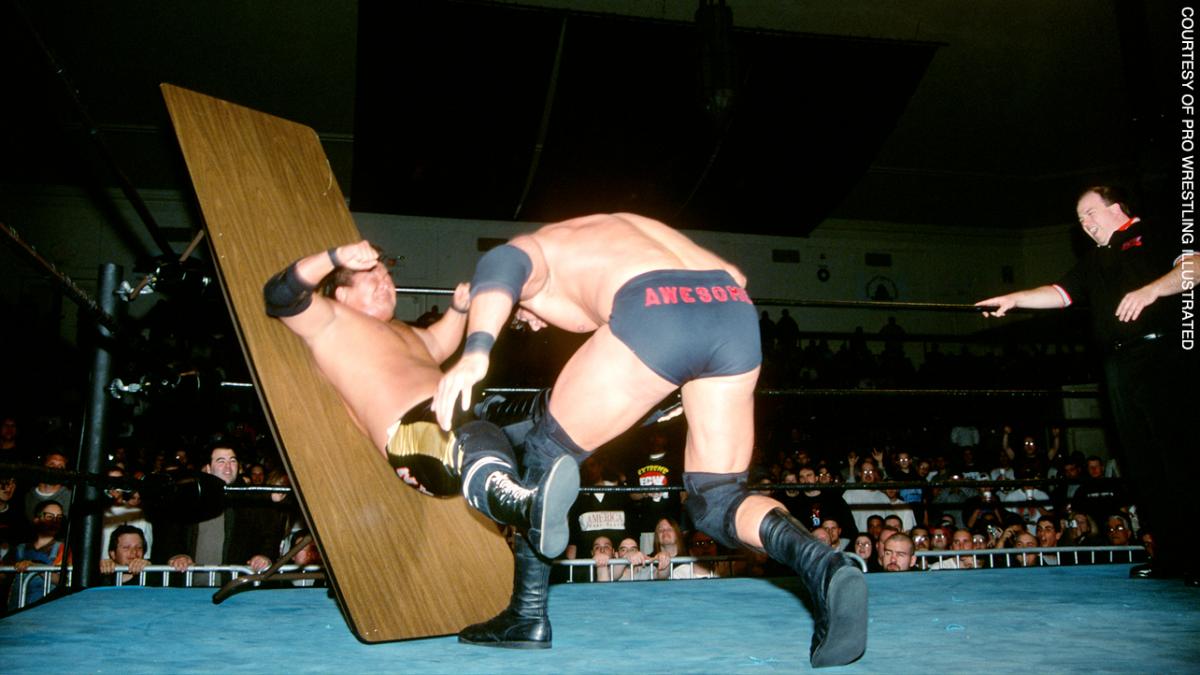

Think of the absolutely incredible series of matches between Mike Awesome and Masato Tanaka in ECW. Those matches were plunder-driven shoot-outs. It’s not reducing things too much to state that Awesome and Tanaka just took it in turns to annihilate one another with chairs and tables before one of them simply lost. The violence did escalate, but not by a great deal. The pace and intensity was effectively non-stop, too. Awesome was the aggressor, and Tanaka the man who endured it. These matches did tell a story - but if you saw a match of theirs written down, it wouldn’t work. It worked because Awesome was a cool badass and Tanaka could take an almighty ass-kicking - and that’s what so much of wrestling is. Craft, psychology, syntax: it doesn’t matter that much. Sometimes wrestling is better when it’s total meathead bliss.

(If you watch an early ‘90s Sting match, he often just loops his ass-kickings and gotcha faces. Sting didn’t really need syntax. He was Sting.)

Hulk Hogan wasn’t a craftsman, exactly. He crafted one perfect, incredibly simple formula and repeated it because it worked for the better part of a decade. He was cut off, he sold, he sold, he couldn’t lift the monster up, he shook his head from side to side and implored the fans to help him, he hulked up, and then he won. There were no dramatic twists and turns in a regular Hogan match. He didn’t need them. He boasted incandescent, almost unprecedented star power.

There's hypocrisy in all of it, a faulty memory that mangles what is already a complicated concept. The psychology of yore is often fake nostalgia. How is the Young Bucks spamming superkicks any different to the countless worked punches you’d see in every other ‘80s match?

Ultimately, you shouldn’t worry too much about psychology. Whatever works, works - and in this era of rampant tribalism, an easy, definitive consensus is further away than ever.