The Complete History Of The New World Order | Wrestling Timelines

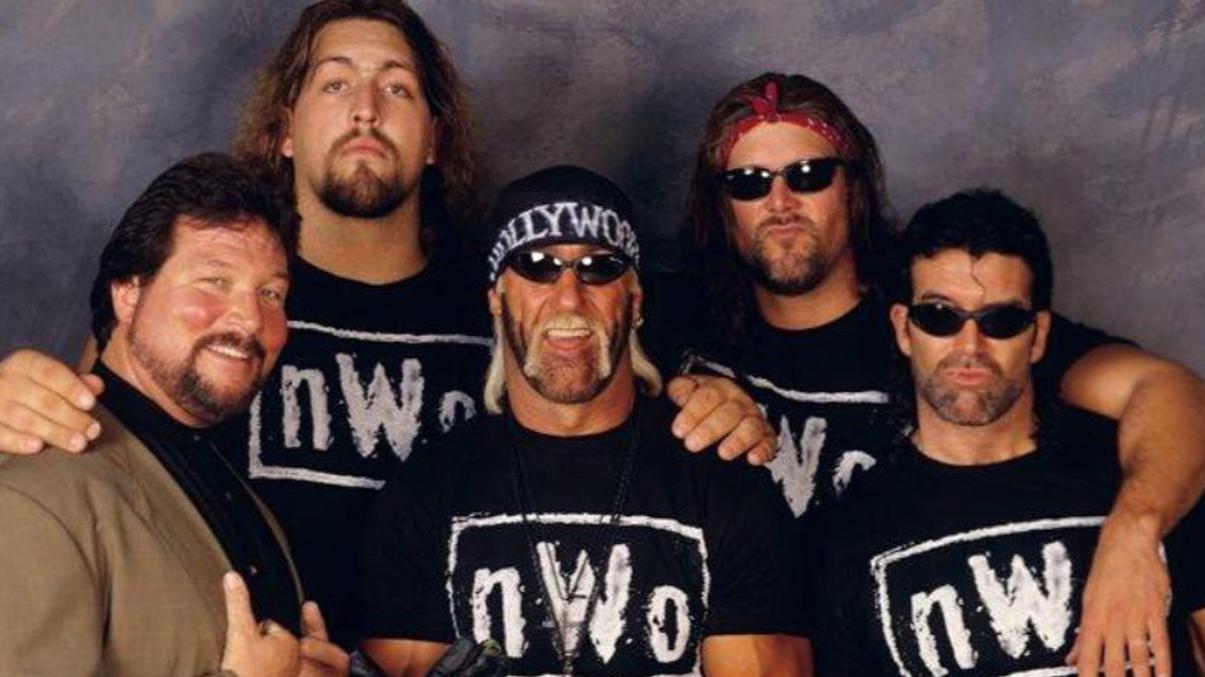

Look at the wrestling landscape: the nWo truly was 4 life.

Today’s pro wrestling landscape is unrecognisable without the New World Order: the most influential stable in the history of the form. The WWE Attitude Era does not happen if WCW Senior Vice President Eric Bischoff didn’t derive inspiration from New Japan Pro Wrestling and Extreme Championship Wrestling. In doing so, he popularised new archetypes: the cool heel and the antihero babyface. Steve Austin played both roles to perfection across 1997 and 1998, all but saving the World Wrestling Federation.

The extent to which the New World Order - stylised as the nWo - radically changed WWE is drastic. The nWo formed in July 1996. That same month, on WWF Superstars, Vince McMahon introduced TL Hopper, a wrestling plumber, to his audience. Hopper defeated Duke Droese, a garbage man, and gagged him with what was purported to be a dirty plunger in the post-match. Vince’s philosophy was either rubbish, or it was in the toilet. Both metaphors apply.

Then, consider All Elite Wrestling.

AEW’s origin story is based on an offshoot of an offshoot of the nWo: the Bullet Club Elite.

Kenny Omega fronted the third iteration of the BC group, or a splinter version of it. The Elite’s self-penned brand of melodrama and irreverent comedy was a gigantic hit that drew record business for Ring Of Honor - and the attention of billionaire Tony Khan. The nWo’s tendrils are twined around wrestling to such a degree that very few new ideas have sprouted since.

The New World Order changed everything - but how exactly did the story unfold, and was it really that amazing in and of itself…?

July 17, 1994 - Hulk Hogan Wins LOL

Hulk Hogan, the man who sparked the 1980s pro wrestling boom, has officially signed with World Championship Wrestling.

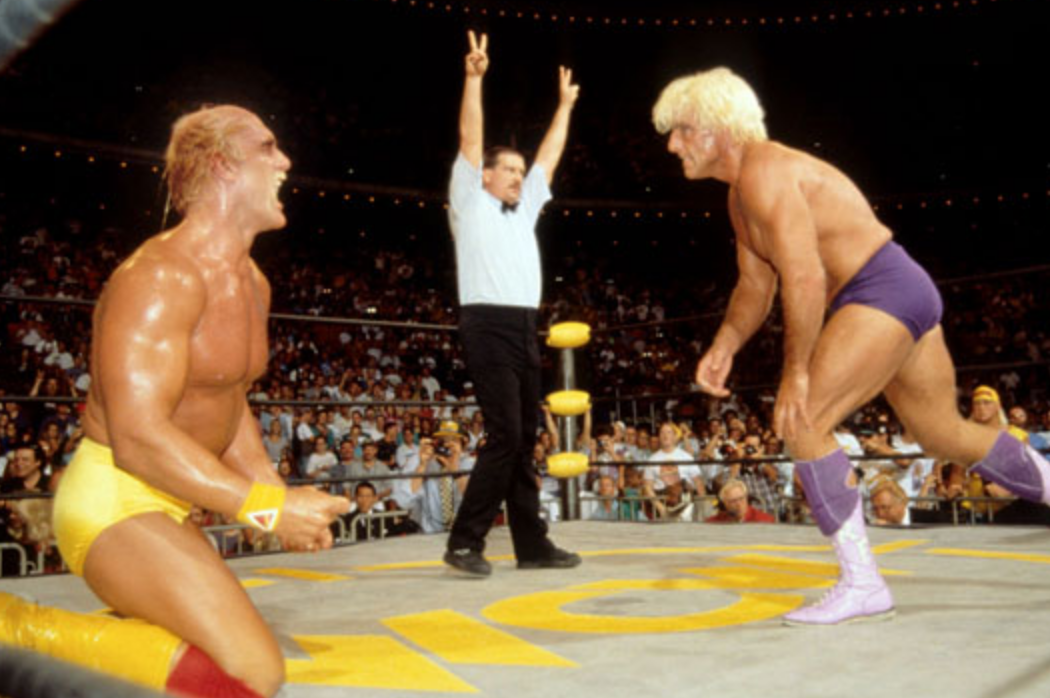

Hogan, in his very first match, dethrones World Heavyweight champion and soul of the promotion Ric Flair at Bash At The Beach. The result, and how quickly WCW arrives at it, is bitterly symbolic. This is Hogan’s promotion now. WCW, in a bid to go big, has abandoned what its core audience gravitates towards.

Hogan’s presence is fascinating and momentous; even the fans of the rugged southern style cannot deny that. Hogan breaks WCW’s pay-per-view record and more than doubles the preceding Slamboree number, drawing 225,000 buys compared to its 105,000. He doesn’t shatter the record, however; the 1990 Great American Bash had drawn 200,000.

The question is asked: does Hogan’s star power truly justify a complete philosophical reset of WCW?

January 8, 1996 - This Is Horsemen Country

Nitro, WCW’s prime-time weekly TV show, goes head-to-head with WWF Monday Night Raw in the Monday Night Wars ratings battle.

This episode - headlined by Hulk Hogan and Randy Savage Vs. Ric Flair and Arn Anderson - emanates from the North Charleston Coliseum in South Carolina.

This is Horsemen Country.

A fan - an aggressive outward redneck with a mean snarl - is stationed front row. As the wrestlers are introduced for the match, the fan turns and faces the hard camera. He holds up some Hogan merch, symbolically rips it in half, and throws up his fingers to show his endorsement of Flair’s legendary Four Horsemen stable.

This fan, GIFs of whom circulate on Reddit and X to this day, memorably embodies the anti-Hogan sentiment evident in many an arena. Yes, Hogan drew record business for WCW on pay-per-view - but he’s not their guy. He draws a casual crowd, albeit not one large enough to spark another boom, but the diehards?

They loathe him and his hokey, cartoonish routine. It used to be magic, it isn’t anymore, and the WCW ultras didn’t even care for it back when it was big time.

The savvy thing to do would be to turn Hogan heel, but this just isn’t going to happen.

Hogan has a creative control clause glowing in his contract that allows him total governance of his own career - and as embarrassed WCW fans will soon discover, the man is hell-bent on convincing them of the power of Hulkamania…

March 24, 1996 - The Alliance To End Hulkamania

In one of the worst and funniest matches ever, Hulk Hogan and Randy Savage defeat the Alliance to End Hulkamania in a Doomsday Cage match. The match, high on the list of worst WCW moments ever, is a triple-decker cage attraction. Hogan must clear each area and pin somebody at the bottom.

The Alliance to End Hulkamania consists of no less than eight wrestlers.

There’s Ric Flair, reduced here to the first weak enemy in a side-scrolling beat ‘em-up video game. Arn Anderson, dressed as a ninja (!), is also easily swatted away in the first level. The Barbarian and Meng, a vastly underrated tag team, are spooky caricatures in the rotten Dungeon of Doom faction. Its leader, Kevin Sullivan, is also thwarted. Lex Luger is a magnificently cocky braggart, but can’t get over in this match. Actor Tiny Lister, who played Zeus in the main event of SummerSlam ‘89, is also there for some reason.

Playing the final boss of sorts is Jeep Swenson, a barely trained actor recruited for his preposterously-sized arms. Until WCW is notified that the moniker is horribly offensive to the Jewish population, he is named The Final Solution. He then goes by the Ultimate Solution. Despite having worked just 20 matches - the Doomsday cage being his last - he is the only wrestler Hogan sells for, and he doesn’t do the job. Flair does the job after a closing melee of frying pan attacks.

Incredibly, there was meant to be a ninth Alliance member: Brian Pillman, who per Dave Meltzer is savvy enough to get elective surgery in the weeks ahead of the PPV.

The total lack of self-awareness is staggering. How did Hogan not ask himself if he was taking this a bit too far at any point?

The Alliance does not end Hulk Hogan - there are eight of them, and they still do not win - but this is the informal end of Hogan’s babyface run. Hogan reaches a point of parody that can scarcely be believed.

April 29, 1996 - Battle Plan

Eric Bischoff - while many of Kevin Sullivan’s ideas are attributed to him - is very shrewd. He’s not particularly creative, and his intelligence will be debated, but he’s at least clever enough to determine what is and is not working in pro wrestling.

He is a magpie.

He knows that the hardcore fans love high-flying wrestlers, since the Super J-Cup and When Worlds Collide are the hottest videos on the tape-trading market, so he builds a state-of-the-art cruiserweight division. (This further allows him to differentiate WCW from the WWF). He knows that Extreme Championship Wrestling is the most fashionable hipster league in the world, so he signs many of Paul Heyman’s wrestlers. Bischoff knows that the WWF is doing terribly at the box office under its cartoonish approach, and senses that fans are gravitating towards a more “edgy” direction in drop-D tune with the wider ‘90s culture.

Bischoff also becomes aware of the hottest, best-drawing storyline in the business after attending NJPW Battle Formation, at which Shinya Hashimoto takes the IWGP Heavyweight title back from UWF-i interloper Nobuhiko Takada in one of the most heated matches ever.

The New Japan Vs. UWF-i programme is short-lived; New Japan stubbornly gets in its own way. It’s white-hot while it lasts, though.

The idea of inter-promotional warfare, of a promotion’s fans standing up for it against a snooty invading force that deems itself superior, is intoxicating. It’s politically complex, and ego inevitably ruins most variations of the invasion storyline, but it’s as close to the tribal thrill of sport that pro wrestling gets.

This gives Bischoff an idea.

(An idea that actually comes back around; in partner promotion NJPW, a splinter group named nWo Japan forms years later.)

May 27, 1996 - Scott Hall Debuts In WCW

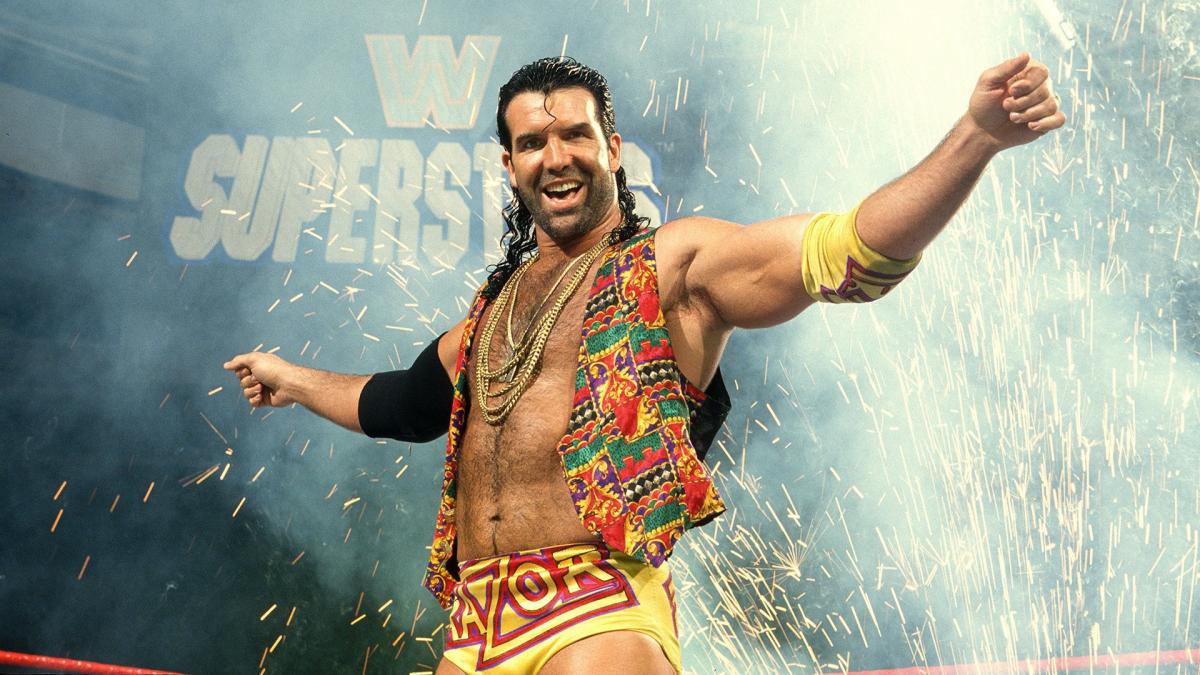

Scott Hall arrives in WCW, lured down south under the promise of more guaranteed money for fewer dates.

The framing of his debut is sensational. It is antithetical to his introduction to the WWF, in which he was introduced via a series of polished, well-produced vignettes.

Hall isn’t repackaged. He isn’t given a copyright workaround gimmick, as was the case with the former Earthquake, John Tenta, who had jumped to WCW in 1994 as ‘Avalanche’. Legal action eventually forced WCW to abandon that idea.

Scott Hall is Scott Hall - or, more accurately, he is still Razor Ramon.

“You know who I am - but you don’t know why I’m here,” he says, interrupting a thrown-out match between the Mauler and Steve Doll. While he obviously is not named Razor Ramon by the commentary team, the heavy implication is that Razor, who speaks in the exact same Scarface-inspired accent, has invaded the territory.

“Razor” speaks as if he’s still employed by the other team. He uses the terms coined by a defensive, shaken WWF when the company had attempted to bury WCW as a retirement league throughout the pathetic ‘Billionaire Ted’ skits. Hall asks where Billionaire Ted (Ted Turner) and the ‘Nacho Man’ (Randy Savage) are.

WCW had initiated the Monday Night War by opting to go head-to-head with Raw. A brilliantly sinister Hall references this in his closing line. “Hey, you wanna go to war? You want a war? You’re gonna get one.”

This is shocking, groundbreaking, electrifying. Razor is not named, and wears street clothes, in WCW’s bid to protect itself.

The WWF legal team was still not satisfied…

June 3, 1996 - Legal Action

WWF owner Vince McMahon, very familiar with promoting star talents from other promotions to get ahead, is nonetheless rattled.

On Raw, he makes it very clear that no inter-promotional storyline is happening. He says that Hall has performed a ruse, further details of which can be found by accessing America Online.

There, it is revealed that the WWF’s legal team has sent a cease-and-desist letter to Hall, who “stayed completely within the character portrayal of Razor Ramon, a registered trademark of Titan Sports”.

The legal department threatens to withhold future royalty payments from Hall until he and WCW drop the pretence.

June 10, 1996 - Kevin Nash Debuts

On Nitro, an intimidated Eric Bischoff, who does a great job of backing away from Hall while staying in shot, asks Hall where his “big surprise” is. Hall points behind Eric as the camera pans back to show the gigantic Kevin Nash, who makes his return to WCW a far bigger star.

Nash grabs the microphone. His very first line is an unintentionally hilarious botch. Questioning WCW’s slogan, ‘Where The Big Boys Play’, Nash says “Look at the adjective: play”.

“Play” is primarily used as a verb, but the introduction is still effective. One line is cute, even if the fans don’t seem to get it: “This show is about as interesting as Marge Schott reading excerpts from ‘Mein Kampf’.

One line is great; Nash asks aloud why Eric can’t find a paleontologist to clear any of the WCW “fossils” for a teased six-man tag.

Really, the content of the promo is immaterial: the fact that it’s even happening is mind-blowing.

June 16, 1996 - “No”

At the Great American Bash pay-per-view, in a bid to dissuade the WWF from filing suit, Bischoff explicitly asks Hall and Nash if they are operating on behalf of the World Wrestling Federation. The explicit answer is “no”.

However.

Hall hurriedly says that they aren’t going to live in the past before once again performing in his past gimmick.

Hall continues to reference WCW characters in the way the WWF did - he refers to Hulk Hogan as ‘the Huckster’ - and dusts off Razor Ramon’s “carve you up” catchphrase. He also continues to use “the Hispanic accent* given to [him] by Titan as part of the character portrayal”. This is cited by the WWF as grounds for complaint in the cease and desist letter.

*The irony, of the character itself being very heavily indebted to Al Pacino’s portrayal of Tony Montana, is evidently lost on Vince.

The WWF proceeds with the suit, which drags on and is eventually settled out of court.

The Bash angle is incredible. Hall demands to learn the identities of the three men who will challenge the Outsiders and their secret partner in the six-man Hostile Takeover match at Bash At The Beach. Ever-hungry for ratings, Eric says he’ll do it on Nitro. This displeases Hall and Nash - so much so that, in a shocker, Nash blasts Bischoff off the stage with his Jackknife powerbomb.

Executed during a time when the table spot had only been introduced to mainstream audiences in November 1995, this is amazing.

It was one thing, to see Diesel plummet through a table at WWF Survivor Series ‘95. Seeing a civilian taking the most violent spot in wrestling is inconceivable. The act that will become the nWo is breaking new ground on a weekly basis. It is must-see, futuristic, transgressive. As a direct result, WCW will very quickly take over as the #1 promotion in the U.S.

The “no” doesn’t matter. Hall and Nash are still playing ex-WWF guys; WCW is having and eating the cake. The thrust of the story, while less believable, is still there. Moreover, WCW has pioneered something equally as alluring as an invading force: the cool heel.

July 1, 1996 - Mabel

Just to clarify a certain narrative…

It is reported in the July 1, 1996 Wrestling Observer Newsletter by Dave Meltzer that the Outsiders’ third man is a certain, not-great former WWF headliner:

“Bischoff, Hall, and Nash were discussing names this past week with Mabel as the top candidate.”

However, in the July 8, 1996 Observer - which was released before Bash At The Beach, but was dated as such for postal reasons - Meltzer gets the actual scoop.

“My feeling is that [the third man is] Hogan because a reader was working on the set of the movie Hogan is doing with Roddy Piper and said that Hogan told Piper he was asked to be the third guy and that he was probably going to do it.”

July 7, 1996 - “But Which Side Is He On?”

The Outsiders wrestle the WCW babyfaces - Randy Savage, Sting, and Lex Luger - at an initial disadvantage. Luger is quickly injured in the storyline to correct the psychology.

Hulk Hogan strides into the Bash At The Beach main event while it’s in progress. On commentary, Bobby Heenan asks: “But which side is he on?”

Strangely, Heenan is criticised for this call in subsequent years - even though his entire genius schtick is to doubt the moral compass of the heroes with the straightest of faces. Moreover, there’s no spoiling the surprise. It is simply too inconceivable.

Hogan - who has played heel before, but in another lifetime and not for well over a decade - drops the big leg on Randy Savage. This is the most jaw-dropping moment in wrestling history. That is not hyperbolic. Even when the magic is gone, the lore of Hulkamania is too overwhelming to comprehend what you are seeing. Hogan is a hero. Hogan “pins” Savage after the match is thrown out.

The “Hogan effect” existed. Before he ruined his reputation, even the people who hated him on tape were cast under his spell live - and these fans in Daytona Beach let him have it.

Hogan gets the name of his own stable wrong at one point - “the New World Organisation of Wrestling!” - but gets everything else right.

In recent years, it was all too easy to disregard who Hogan was, since he was playing a caricature of a cartoon character. This, instantly, is different. With his gruff voice and gigantic frame, Hogan within seconds becomes threatening, nasty.

Gene Okerlund is superb at registering his disgust as Hall and Nash mock Hogan’s old posing routine in the background of the shot. Hogan explains his actions. He says that “Billionaire Ted” promised him movies and marquee match-ups.

In a genius line, Hogan says “I’m bored, brother”. This is great. The boredom is obvious, a feeling WCW fans know all too well. Hogan is going through the motions, with his awful monster-of-the-week formula, and he has the temerity to say that he’s bored?

It’s so easy to resent him. He is Hollywood Hogan now.

In an iconic scene that will become very familiar, Hogan is pelted with garbage. The scene is alive and real, a feeling intensified by two stunning ad-libs. Gene says the garbage is fitting; that’s who Hogan has aligned himself with. Hogan plays off Gene playing off the detritus, saying “all this crap in the ring represents these fans out here”.

Setting the promo template for virtually every turn thereafter, he blames the fans, telling them to “stick it”.

The big bang just happened. Everything changes subsequently.

July 29, 1996 - Rockhouse

The nWo debut their theme ‘Rockhouse’ on Nitro. This, arguably, is the greatest theme in pro wrestling history. Certainly, the best non-licensed one.

It’s a soundalike composite of several Jimi Hendrix cuts.

This is an ingenious idea because Hendrix’s work is eternally cool. It never ages, and while this riff on it is heavily distorted, at a time when nu-metal is lurching onto the airwaves, it too never dates. ‘Rockhouse’ fits the time but is not damned by it, either.

A deep, heavily modulated spoken word sample says “New World Order”, repeating the word ‘New’ several times.

This single idea conveys both the intimidation factor carried by the stable, and the extent to which they run roughshod over Ted Turner’s organisation. It is an absolutely stunning, rousing, almost scary composition. The modulated effect is jolting, even after repeated listens.

The twilight setting of the Disney MGM studio is an ideal backdrop for this violent, above-it-all force. The darkness is about to descend.

It’s little wonder that the young adult males fall in love with the heels.

July 29, 1996 - Lawn Dart

The date is not a mistake; on the same show, the nWo is responsible for another iconic pro wrestling moment. This era of Nitro is amongst the greatest run of shows in episodic TV history. The idea is groundbreaking.

Where previously, the action was confined to the ring and the backstage area, WCW, or rather the New World Order, opens up the terrain. Jimmy Hart sprints to ringside, telling of a commotion. The direction here is superb, attentive. There are no cameras stationed in the production area because nothing is “meant” to happen there. There is no sense of contrivance; only chaos.

The camera operators run backstage to discover that the nWo has invaded the show again. This is sold expertly by a beleaguered, appalled commentary team, who look shaken as they attempt to uphold their professionalism.

The sanctity of Monday Nitro as a broadcast, with scheduled matches designed to advance wrestlers up and down the card, is under threat. This is critical to the success of the storyline. It is must-see television; you are meant to think that there might not be a WCW left, when the nWo is through with it.

The brilliant yet tiny Rey Mysterio, intent on fighting off the interlopers, is met by Nash near a production truck. In a gruesome spot that looks phenomenally ill-advised - and positively awesome - Nash throws Rey against it with a lawn dart. Everything you knew about pro wrestling is being disrupted, mangled.

We’re taking over.

August 26, 1996 - An Incredible Idea

In what is a sensational idea, Ted DiBiase, the former ‘Million Dollar Man’, becomes the fourth member of the nWo on Nitro as the ‘Benefactor’ of the group. In a deft bit of foreshadowing, he walks through the crowd and stations himself ringside as the Giant - who will become the fifth member, lured in by Ted’s riches - makes quick work of Jim Duggan.

DiBiase as benefactor fills in the gaping plot hole. If Nash and Hall aren’t contracted to WCW, who is paying them?

The angle is so hot - incandescent - that the fans aren’t exactly asking the question, or letting it get in the way of the unmissable chaos into which Monday Nitro has descended. That said: the idea is an inspired attention to detail, grounding the onscreen chaos with a narrative elegance that rewards investment and builds trust in the creative process.

The answer is DiBiase, who in WWF storylines was a vastly wealthy mega-heel. In a very cute bit, since he shares the same forename, he is nicknamed ‘Trillionaire Ted’ by his stablemates.

His performances are well-reviewed, but that doesn’t seem to matter…

August 26, 1996 - The Presentation

Again, the date is not typed incorrectly: WCW is so on fire that every week is stacked with jaw-dropping developments.

In another heavy heat angle, the nWo, wearing the black and white tees, attacks WCW representatives on Nitro. It’s staggering, just how instantly distinct and iconic the faction is. Hogan begs off Steve McMichael. The endearing wrestler, who is not good technically but still believable, is attacked by Hall and Nash, who spray-paint the nWo initials over his back. Sting is also beaten down before Ric Flair and Arn Anderson make the save and inspire hope. That might not be the correct term, in a new landscape in which the language is evolving as quickly as everything else. Do the fans “hope” to see the nWo receive their comeuppance?

It’s an amazing scene, all the same, as Hogan spray-paints and in effect dyes Ric Flair’s signature bleached hair black - symbolising that a new era is here. The use of dark colours is inspired.

The context is so important to consider here. Before the nWo arrived, mainstream pro wrestling in the United States remained a 1980s hangover. Detached completely from the wider cultural zeitgeist, the WWF (and WCW) is a garish, multi-coloured relic of a more naive time. A lot of hand-slapping babyfaces do not resemble the hip celebrities of the day as grunge and nu-metal battle for genre dominance, wearing instead luminous, hyper-patterned attire. Order member Hall, who credits himself with masterminding Sting's look, refers to this look as “happy guy tights”.

Bischoff will later state that this was a conscious exercise in contrast. The WWF was too colourful; to enhance the mystique of the nWo, he wanted “an underground vibe”. This new idea is plastered everywhere.

Hogan’s new look - he grows in thick black stubble - is a genius choice. He looks unrecognisable and iconic, all at the same time, in this new, scary world of contradictions in which the heels get cheered. It’s a surreal, unsettling effect.

This extends to the paid announcement videos shot and financed by the nWo, to credibly allow them screentime. Produced in black and white with a grain effect, they’re great, even if Hogan’s performances are a bit over-the-top. They are also sold to perfection by Tony Schiavone, who expresses confusion over which promo segment to throw to next.

The sense of disorder is beautifully done. The WCW wrestlers question the allegiance of the production truck, demanding this “garbage” doesn’t make it to air.

The world quite literally becomes a darker, more hostile place.

September 16, 1996 - Sting: Origins

Sting still looks like the Surfer of old as he makes his way to the ring on Nitro. In a great touch, he will later build the tension of his suspect loyalty by daubing himself in black-and-white.

The week prior, the nWo debuted ‘nWo Sting’ (Jeff Farmer) in a bid to convince the WCW roster that the real deal had turned - a contrivance made possible, and just about plausible, through Sting’s face-painted look. At Fall Brawl the night before, Sting came to Team WCW’s rescue, proving that the imposter was helping the nWo, but left Luger to the wolves in a measure of revenge.

Sting grabs the mic and cuts the promo away from the hard camera - a tease, picked up on commentary, that he is turning his back on WCW. While the symbolism doesn’t quite work, since it is made explicit, this is nevertheless highly sophisticated by the standards of U.S. pro wrestling narrative.

Tying up and making sense of a well-received but dropped angle, in which he played face as his mate Lex Luger played heel in secret, Sting says that he’s tired of giving Luger the benefit of the doubt only to be questioned by him.

“If you stand by me, I’ll stand by you,” Sting says, before addressing his doubters. Those who doubted him, he says, in a great red herring, “can stick it”. This, in no coincidence, is what Hogan said during Bash At The Beach.

“From now on,” Sting wraps up, “I consider myself a free agent. But that doesn’t mean you won’t see the Stinger from time to time. I’m gonna pop in when you least expect it.”

In a secret hint that he is a babyface, Sting is true to his word. Until December, he doesn’t wrestle a televised match in 1997 - but he becomes the defining figure of the year…

October 21, 1996 - The First Glimpse

On Nitro, Sting attacks his evil doppelganger. This is the first time we glimpse what is the first true phase of the man that will come to be known as ‘Crow Sting’.

He is in black and white face paint.

Sting wears the colours of the nWo, but beats up one of their own: a note-perfect introduction to his new mystery arc as an enigmatic vigilante.

He also wears - and this is inspired - a black leather trenchcoat. The black trenchcoat is synonymous with the cinematic badass, but worn by the wrong person, it becomes pitiful in its aspiration of danger. You have to be able to pull it off.

Sting pulls it off.

October 28, 1996 - The Rafters

In what will become a familiar, haunting, hypnotic sight, Sting is seen watching on from the rafters as Lord Steven Regal and Juventud Guerrera wrestle a match on Nitro.

What’s he doing?

Is he mulling over his decision?

Or is he waiting for his time to strike?

November 18, 1996 - A Slightly Less Good Idea

Eric Bischoff, who was brutalised in various early angles, is revealed to be the real mastermind behind the nWo. Trillionaire Ted is phased out.

Roddy Piper questions and prods Bischoff. He is adamant that Bischoff has something to do with it, and the clues are there; while DiBiase finances the organisation, who is actually allowing the anti-WCW propaganda to make air?

The execution of a well-teased reveal is brilliant, as Bischoff beams a smug smile when the nWo encroach.

Bischoff is good in the role, a total smarmy bastard, which adds a much-needed complexion to a unit so cool and so over that only the very best babyfaces stand a chance of staying over when stood in the same ring.

Still, while Bischoff has the power to facilitate the nWo, the alignment barely connects to the events of June, and the Hogan/Bischoff dynamic yields more droning, not-great promos than bombastic angles. The nWo is firmly established at this point, which is just as well: does the movement become as big as it is, if this is how it starts?

The more cynical fans maintain that Bischoff is an egomaniac who wants in on the fame.

In an early battle of what will become a lifelong war between both sides, Dave Meltzer is even more damning of Bischoff, writing in the November 25 Wrestling Observer Newsletter:

“They wanted to put the nWo head-to-head with Raw. And Eric Bischoff wants to be on the air at the same time as Vince McMahon. It’s that simple and there’s nothing more to it than that.”

Meltzer concedes that “[it] was an idea that was rumoured for a long time and may have been considered for a while”.

November 18, 1996 - Dimming The Rose-Tinted View

The prevailing narrative, in the years to come, is that the nWo was a great time for two years - but even in 1996, this is questioned.

In a letter to the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, subscriber Lance LeVine writes the following:

“Week after week we see Hogan and his cronies laying to waste the faces as well as the heels for that matter. Nobody could possibly believe that anybody in WCW stands a chance against the nWo at this point. The original concept is a solid one. The interpromotional feud. But in typical WCW fashion, its execution has been completely botched.”

Does the one-sided nature of the WCW Vs. nWo feud explain the imminent disaster of January 1997?

December 29, 1996 - The Roddy Piper Business

Roddy Piper has a run in WCW that can only be described as drastically uneven, ranging from the very best (realistic) version of itself to some of the worst pro wrestling TV and action ever.

Piper’s delivery is incredible, the contents of the promos inscrutable. He is broken-down to a bleak extent, but it so charismatic that, early on, the fans go banana for him anyway.

He beats Hogan at Starrcade in a great, albeit arthritic, spectacle. The title isn’t on the line, which is beyond nonsensical, but alas. The fans cheer Piper over the nWo - emphatically. The build is great; Piper is effectively promoted as a living legend via brilliant, ardent endorsements from Ric Flair and Arn Anderson.

The Piper run will get downright weird and embarrassing.

Ahead of Uncensored ‘97, at which Piper and Hogan renew hostilities, Piper visits Alcatraz prison to train in an infamously lame vignette. Then, before abandoning them for the Four Horsemen in less than a week, Piper tests and fights a strange cadre of wrestlers to join his very quickly estranged ‘Family’ - which is the least relevant word for that non-stable imaginable.

At Halloween Havoc ‘97, as WCW opts to rehash Hogan Vs. Piper yet again, they participate in what becomes known as ‘Age In The Cage’. The men are just 44 and 43, respectively, but this is ancient for the era, and the characters have hung around forever.

The action is awful, the WrestleMania 1 novelty is dead, and the match highlights the year-on-year decline in the quality of creative.

January 25, 1997 - Souled Out

The New World Order presents “its” first-ever pay-per-view: Souled Out.

It was also the only nWo pay-per-view, because Souled Out is a critical and commercial disaster.

It looks the part. Across every detail - the set, the signage, the broadcast personnel - it feels like a distinct spectacle produced by a “different” company.

Strangely, by its very, mega-flawed design, it is a punishment of a show. On commentary, Eric Bischoff and Ted DiBiase bury the babyfaces and don’t pop for anything they do during the WCW Vs. nWo matches. It is a deflating experience. Heel referee Nick Patrick is installed to officiate the matches and essentially let the heels win. This renders the show so pointless that when some babyfaces do win, there’s no drama nor catharsis. The heel winning should be a guarantee.

Each WCW wrestler walks to the ring in silence as the nWo ring announcer pokes fun at them. They walk past three rotund fellows who for some reason or another are sitting on the stage. Are they meant to look like the scuzzy low-lifes that the nWo hang around with, being mean and surly, in their free time?

This glimpse into the nWo extended universe, and really, the show itself, is above all else lame. It is unbelievably lame, a complete betrayal of the nWo’s core appeal.

The nWo works on a specific principle: they are cool badasses. What was once an exclusive club is ballooning by the time Souled Out is promoted. Is the former IRS, Mr. Wallstreet, cool?

Souled Out is a single, obnoxious punchline dragged out over three hours. The show begs a question that is less than ideal: what are we doing here?

If this is the nWo’s ideal world, the end goal, it is awful. Souled Out illustrates that there is no viable ending to the storyline - unless it’s a happy one.

People have now seen what a New World Order takeover actually looks like. The threat is delivered upon, and it feels like a punishment. The nWo only works when they threaten the sanctity of a functional wrestling card that is run properly. The fans must have sensed this going in. The Order formed at Bash At The Beach 1996. Every pay-per-view thereafter drew in excess of 200,000 buys. Even before it is executed abysmally, Souled Out draws 170,000. The concept is a dud.

Just one match is of value: a cracking ladder war between Syxx and Eddy Guerrero, who is so awesome that he wins the rigged game. This might be the catalyst for the later protests; many fans hope that the cruisers are pushed further up the card as the nWo main events become tedious.

It’s a dismal night for what remains the biggest thing in wrestling. There’s one simple solution to the problem: effectively promote star babyfaces. For a story based on groundbreaking inter-promotional warfare, the nWo angle actually functions best when it plays the classics - when a good guy rises up against a gang of baddies.

1997 is off to an awful start - but three men prove that babyfaces can still be cool, too.

January 20, 1997 - The First Rappel

A now mute Sting has been attacking WCW representatives - Jeff Jarrett, Rick Steiner - but why?

Is he yet to forgive WCW for failing to trust him - despite being the first WCW guy to stand up to the nWo? Or is he playing a long game of deception?

The only thing for sure about Sting is that nothing’s for sure.

He has also pointed his bat at the nWo, signalling his intention to dismantle the group, and issued loyalty tests to the WCW guys. He points the bat at them. He waits for their reaction. He turns his back. If no retaliation is incoming, he seems to express approval with a subtle nod. The idea, and fans are latching onto it, is that he wants their trust back before he goes to war.

He issues a test to wrestling pioneer Randy Savage, setting up a short, dropped alliance between the two men, before which - for the first time ever - he rappels from the rafters.

It’s an intriguing sight, and it will become awesome when he drops from the rafters into the ring, destroying the nWo in the melee of a heavy heat angle.

The importance of Sting, specifically, cannot be overstated. At its very core, from day one, the nWo is the most flawed successful concept ever. The nWo exists to put over the babyfaces in WCW, but the unit is more over than the babyfaces. They, in effect, are the babyfaces.

Sting, crucially, is the one entity cooler than the New World Order. His presence is electrifying, his look, heavily inspired by ‘The Crow’, is the business. The rafter drops, holy hell: the live, cinematic action set-pieces are unlike anything wrestling fans have ever seen. Sting is a megastar babyface, but he transcends that; if wrestling is all about building hype and anticipation, the incredible concept of a living superhero - who will only step into the ring when the time is right - is a promotional masterstroke.

It is imperative that he wins in the end.

March 16, 1997 - Decision Made

At Uncensored, Sting descends from the rafters to attack Hall, Savage and Nash in the closing scenes of the pay-per-view. He then challenges Hogan to enter the ring. Hogan accepts, and gets his ass kicked too. Sting has aligned with WCW.

July 7, 1997 - A Smart Babyface At Last

In a superb and memorable angle, Randy Savage, who has since defected to the nWo, readies himself for a match against masked luchador La Parka.

Savage doesn’t take it seriously. He taunts the crowd throughout. Scott Hall is supporting his stablemate at ringside, but is so sure of Savage’s win that he ventures up the ramp to intimidate Tony Schiavone at the commentary table.

Randy’s opponent is not La Parka. It’s Diamond Dallas Page in disguise. This is revealed when Page gets his legs up to counter Savage’s elbow drop, and drills him with the Diamond Cutter. In a great touch, Hall celebrates with his back to the ring, assuming that Savages has just won an easy tune-up match. DDP unmasks and high-fives members of the crowd - who are so thrilled with the development that they momentarily forget they are clad in nWo merch.

1997 is DDP’s breakthrough year. The fans gravitate towards him because he embodies several admirable babyface traits. He’s clever, with an ability to fool the heels into taking his Diamond Cutter finish from exciting, unpredictable set-ups. He’s a grafter, having broken into the business as a wrestler very late. He’s got a great taunt and catchphrase. He can flat-out go, which is a prized attribute to fans that still value great in-ring work.

Even he can’t really get it done against the nWo; while he is cheated, he loses the well-received programme to Randy Savage in the end, and is beaten down by the group in a disqualification “win” over Hulk Hogan on the October 27 Nitro. He’s a rare WCW success story, in that he is cheered throughout his battles with the Order and enjoys a well-received stint with the United States title, which he wins at Starrcade. It’s a net positive, when you consider that he isn’t meant to be the guy who takes down the nWo once and for all. That’s Sting’s role.

Sting will save WCW.

Surely…

August 4, 1997 - Luger Wins!

Lex Luger is one of the three key babyfaces in the fight against the nWo.

The nWo remains white-hot; while the WWF is getting its sh*t together creatively, and how, we are deep in the ‘83 weeks’ era of consecutive Nitro wins in the Monday Night Wars ratings battle. The nWo also remain an unstoppable force, having held the WCW World Heavyweight title hostage since August 10 of the prior year, when Hogan dethroned the Giant at Hog Wild.

Spray-painted with the logo, it is referred to by members of the faction as the nWo World Heavyweight title. The nWo’s invincibility heats up the faction, but renders the week-to-week experience of Nitro a constant blitz of heel heat.

Luger shockingly wins the World title on Nitro. It’s thrilling in and of itself, and the sensation is dreamlike, since the main event was made on an impromptu basis earlier in the show.

In one of the most enduring moments in Nitro history, fondly remembered forever for its rare, true joy, Luger cleanly defeats Hogan with his Torture Rack submission to a mass eruption of a pop. Luger is beloved, had apologised for not trusting Sting in a great, heartfelt promo delivered on the November 11, ‘96 Nitro, and his cocky demeanour, once a bit off-putting, soars in the era of the cool heel - but he isn’t Sting.

The purpose behind this glorified ‘Dusty finish’ is questioned when Hogan regains the title days later at Road Wild. What WCW accomplishes here is twofold.

The monotony of the nWo is suspended. It was getting a bit much.

Also, ahead of Starrcade, the fans are conditioned to believe that Hogan is capable of doing a job.

September 1, 1997 - Sign Of The Times

In a parody angle so brutally funny and incisive that it genuinely upsets the target, the nWo mock the Four Horsemen on Nitro.

Kevin Nash dresses up as Arn Anderson, putting more effort into a heavily detailed prosthetics job than he applies in the ring. The attention to detail is astounding. He makes himself look authentically ancient. Among other impersonations, the other highlight is Sean ‘Syxx’ Waltman playing Ric Flair, in or constantly on the verge of tears.

It’s a sign of the times; the front row redneck is gone, and the Horsemen getting buried is funny now.

It’s also another reminder that the heels are probably too over.

December 8, 1997 - Over-Ambitious

It is reported in the Wrestling Observer Newsletter that “the working idea for 1998 is to split WCW and nWo into somewhat separate entities, each having their own television shows. The grandiose idea behind all of this would be to make the WWF into the third biggest wrestling company in the United States”.

In December 1997, the WWF is the second biggest company.

The ranking of Vince’s promotion will change in 1998 - but it won’t be third…

December 22, 1997 - nWo Nitro

The much-rumoured nWo Nitro happens, when the stable “takes over” Monday Nitro.

The nWo hangs their signage over the set as Bischoff, Rick Rude and Kevin Nash perform commentary duties. It’s not as obnoxious as the Souled Out broadcast booth - they put the babyfaces over - but then, that makes the whole bit pointless. An impartial booth doesn’t make sense. A heel booth is damaging.

There might be no way this works.

nWo Nitro is Eric Bischoff worshipping Hollywood Hogan for much of an hour. Bischoff presents Hogan with an array of gifts and serenades him with holiday songs.

It ends, infamously, with Sting and Bret Hart giving Hogan a gift of their own. It is a mannequin head of Hollywood Hogan. Hogan sells for this as if he has been decapitated and is staring at a part of his own corpse. Shaking violently, he is frightened by what is a corny bit of symbolism. This is the least cool Sting stunt, and the timing is suboptimal.

This is the closing shot of the Starrcade ‘97 go-home show.

This specific idea for an isolated ‘nWo Nitro’ might all work, if it is framed as an oppressive dystopia - a smug, deliberately unentertaining segment designed to evoke groans.

This is what might become of Nitro, if Bischoff wins at Starrcade, and Sting doesn’t prevail!

But that’s not what we’re doing here: what we’re doing is a pilot of a proper nWo show. The threat of a weekly Souled Out 1997 is about as effective as it sounds.

This is so poorly-received, even dropping half a ratings point, that the idea is abandoned. The imminent second WCW weekly TV show, imposed by Turner, will go by ‘Thunder’. It will be a WCW show with minimal effort put into it - more of the same.

“More of the same” will come to define WCW over the coming year.

December 28, 1997 - Starrcade

The end is nigh.

Starrcade is WCW’s biggest ever night. The pay-per-view sets an unbroken buy amount of 700,000. It is the peak. The only way is down.

Even before WCW enacts the first critical phase of its self-destruction, the atmosphere is strangely subdued, given the occasion. Isn’t Starrcade meant to be a highly-anticipated, jubilant celebration? There should be tension in the air, no?

The undercard is poor and bereft of heat. In an ominous sign for 1998, the hottest and most discussed free agent in wrestling history, Bret Hart - who is the best wrestler in the world at the time - is rushed into WCW as the special guest referee for a terrible match between Eric Bischoff and Larry Zbysko. Weirdly, it is a comedy match with the highest of stakes: control over Nitro. WCW rep Zbysko wins.

The main event is an infamous, soul-destroying dud.

Sting looks slight and, yes, pale. Hogan dominates a short, one-dimensional match. It’s very far removed from the pulsating, dramatic epic that fans had in mind for this grand moment of retribution.

The finish is amongst the flattest of all-time. Hogan hits the big boot and the leg drop. Heel referee Nick Patrick is meant to do a fast count, in order for Hart to reverse the decision - but it’s nowhere near fast enough. It looks like Hogan has won fair and square, and when Sting beats Hogan in the impromptu rematch, it's lifeless.

In the years to come, Bischoff will deflect accusations that Hogan instructed Patrick to forget the fast count. Patrick will claim that between Bischoff and Hogan, one person told him to do it, while somebody else told him to keep the count “nice and slow”. You can probably work out which person is which. Certainly, Hogan’s legendary reputation as a politician damns him in the eyes of many.

A convergence of factors informs a terrible, deflating night - by his own admission, Sting, battling personal issues, isn’t in great form. Not working for a year was a great promotional tactic, but a flawed one. He isn’t remotely sharp.

One factor that isn’t considered is that Sting’s epic takedown of the nWo doesn’t happen because that would require WCW to actually rid itself of the faction (and the attendant merchandise money). It goes beyond an easy addition to the balance sheet. The nWo encompasses the narrative so thoroughly that WCW would have to completely reimagine itself from the top to the bottom of the card.

The nWo is also too easy to book. So many episodes of Nitro go off the air with heavy heat beat-downs and a babyface lying face-down with the nWo logo spray-painted on his back. The nWo is incredibly repetitive - which is fine, when people are into it. What works works. But when there’s no chance of justice, why bother?

A company almost defined by lazy incompetence isn’t going to put any effort into crafting a new overarching storyline.

The company lacks the nous and the desire to do that, and the top guys are hardly going to play along with the idea. Even if WCW is somehow willing, who’s going to tell Hall and Nash that they’re no longer permitted to play the cool heels in the main event scene?

The power they wield is too vast.

If it works, do more of it. Do more of it, and people grow bored. That is the cause of and solution to the problems inherent to capitalism.

WCW is not an outlier.

February 23, 1998 - The Disciple Joins

Again: the New World Order is meant to be cool. If you want to be reductive about it, that is the stable’s key selling point. Hogan is cool by proxy, and works in the context of the stable because he grounds it with actual heat, but the collective is (or was) cool.

Nash and Hall are aloof, handsome mercenaries who radiate a sense of entitlement, but are equipped with the size and power to pile sympathy on the babyfaces. It’s this dichotomy with which the nWo can both sell warehouse-loads of t-shirts and - on occasion, anyway - get a babyface over.

On February 23, the Disciple joins the nWo as yet another favour to Hogan.

There are already far too many bad nWo members by February ‘98 - Brian Adams, the artist formerly known as Crush in the WWF, had joined just a week earlier - but we cross the rubicon here.

The Disciple is Ed Leslie, the former Brutus ‘The Barber’ Beefcake. He is a punchline - more over in the ‘80s than his reputation indicates - but a punchline, nonetheless, who has played various dismal characters in WCW to give him something to do.

A thrashed artifact of a different time, the Disciple is a tedious nonentity. He has nothing going for him; he isn’t cool, talented, over, nothing. He is a void, a living embodiment of the idea that the nWo is increasingly meaningless.

In parallel, the WWF is becoming cool, and a few weeks earlier, on January 19, Steve Austin had engaged in a pull-apart brawl with Mike Tyson. It was easier to believe that Austin could beat up a former undisputed World boxing champion than it is to believe that the Disciple, and by extension the nWo itself, is cool.

This exercise in contrast is less than ideal.

May 4, 1998 - The Wolfpac

After months of simmering dissension within the nWo, the nWo Wolfpac, made up Nash, Savage and Konnan, debuts on Nitro as a new babyface splinter group. This follows the events of Spring Stampede, at which Hogan betrayed Nash.

WCW gets the presentation and the dynamic right. That’s an understatement, really; the doomy hip-hop beat of the Wolfpac theme is incredible, and the red-and-black nWo logo variant shifts yet more warehouses of merchandise (as does the 'Wolf' tee). The nWo as intentional babyfaces: on one level, it’s a masterstroke.

The opposing squads are contrasted to great effect. Nash essentially played a cool babyface the entire time. Savage was always the coolest household name of the ‘80s WWF boom. Konnan, while his in-ring work has deteriorated to a shocking degree, was one of the most marketable stars in modern lucha libre history, dresses to the times, and is a phenomenal, quick-tongued promo.

The nWo Hollywood group, meanwhile, is fronted by Hogan. They are the heels, and they range from intimidating and convincing (Scott Steiner), massively irritating (Buff Bagwell) and so boring that the fans resent them (the Disciple et al).

This civil war is a great idea. The execution is less than stellar. WCW, despite repeating the same pointless swerves and adding too many additional members, again, is not at fault for all of it. Hall is on and off television battling substance abuse issues. This flattens the potential of the storyline. Worse, at Slamboree on May 17, he betrays Nash - even though he is ideally cast in the Wolfpac, and WCW could have developed that storyline long-term.

Complicating the whole thing further, and the potential of Nash as the top guy, is the unexpected rise of a new major star.

July 6, 1998 - Goldberg

Sting had won the title back at Superbrawl, having been stripped of it as a result of the controversial Starrcade finish, on February 22, 1998. While the event draws an impressive 415,000 buys, it’s too late. The idea of Sting as the saviour has faded away, which might explain the meagre 275,000 drawn for his second and final PPV title defence against Randy Savage at Spring Stampede on April 19.

That, and the resurgent WWF ramping up in popularity.

WCW, though, has an awesome new weapon in the war: Goldberg, one of wrestling’s most unbelievable physical specimens ever, who had not made his professional debut when the nWo first formed.

There’s no grand, 15-month plan to build Goldberg. He simply explodes in popularity, and even WCW, which is in near-constant systemic disarray by this point, isn’t stupid enough to stop him. At least, not for a while.

(On that: in WCW, in 1998, the detailed, long-term planning that really only barely existed is no more. Of the few plans that are made, many are rubbished by the top wrestlers who hold too much creative influence. In the March 16, ‘98 Observer, Meltzer reports that Hall and Nash are locked in a backstage feud with Hogan and Bischoff. The firing of Hall and Nash’s close friend Syxx is particularly contentious. Hall and Nash make noises about leaving; they are reminded by Bischoff that they’re tied to WCW until 2001. Nash doesn’t want to perform a spot in which the Giant gives him a powerbomb; Hogan purportedly makes it happen. With his power diminishing, until he gets a stint with the booking pencil in late 1998/early 1999, Nash’s response is to stop caring.)

Bill Goldberg is a former defensive NFL tackle who pioneers one of the very best and certainly the most imitated moves in wrestling history: the spear. He looks like he’s trying to bend his opponents in half backwards at the hip. He is reckless, but so intense and believable that he elicits an almost involuntary, animalistic response from the crowd.

In ultra-short matches - “massacre” is a more appropriate word - Goldberg gets over to a mega-star level.

In a stunt move that should make pay-per-view, Goldberg defeats Hogan on Nitro in part because Nitro had been annihilated by Raw in the ratings the week prior. A fortune of potential PPV buys is burned. Only when you actually picture the stack of cash, ablaze, do you get a sense of how short-sighted the decision is.

In front of the fourth-biggest crowd in pro wrestling history to this point (41,412), after pinning Scott Hall to get the match, Goldberg dethrones Hogan, who naturally has his belt back.

Goldberg sets the Georgia Dome alight. The pop is deafening, an all-timer. Hogan, rarely praised for his selflessness, actually sells his ass off and lays his stuff in. Entering one of his best and most motivated individual performances, Hogan could not do more to establish Goldberg as the authentic article. WCW has a new top babyface.

Steve Austin is outdrawing Hulk Hogan’s peak over in the WWF - but the war isn’t over yet.

June 1, 1998 - The Unthinkable

Sting officially joins the nWo on Nitro.

It’s not quite the sort of terrible, desperate plot twist that defines dying, idealess entertainment properties - he joins the Wolfpac and the stated mission to take down Hollywood Hogan, so it’s somewhat consistent with his character - but it does beg the question: what else you got?

Does everything have to in some way involve the New World Order, the original aim of which is now totally lost?

August 6, 1998 - Desperation Sets In

In what is becoming typical of a promotion so slipshod that it will earn the nickname ‘LOLWCW’ posthumously, WCW actually solves the nWo problem, but doesn’t really do it. The Wolfpac Vs. Hollywood programme barely happens.

Instead, the respective leaders (of the sub-factions that still exist) are preoccupied with other matters. Hogan embarks on a disastrous odyssey with celebrities. WCW has done this before - Chicago Bulls bad boy Dennis Rodman joined the nWo in March ‘97, and headlined Bash At The Beach that year - but it’s much, much worse a year later. Rodman teams with Hogan at the Bash again, against DDP and Karl Malone, but falls asleep mid-match. Then, with Bischoff desperate to gain ground on the runaway WWF, Hogan teams with Bischoff and sells for DDP’s tag partner: anti-athlete and very, very famous late night talk show host Jay Leno. The main event of Road Wild is a farce. The idea is to draw more casual fans to WCW. WCW consequently becomes a very lame laughing stock.

Compounded by just how over and fashionable Steve Austin is, WCW formally dies, R.I.P., as the cool U.S. major.

October 25, 1998 - WCW Is A Joke

The rise of antihero Steve Austin does not happen without the nWo.

In another publicity stunt, it’s now Bischoff’s turn to borrow from the WWF, which is well into its second boom. Austin is the man, but the creative direction, teeming with sex and bad taste controversy, is a hit with young adult males. Bischoff believes that is the path WCW must take. He is catastrophically wrong.

As is the very idea of Kevin Nash Vs. Scott Hall. Hall’s alcoholism is now his gimmick, which plays into the match. It’s slow, plodding, drastically removed from a heated grudge match between two former friends. Nash trash-talks Hall and mimes opening a beer before hitting him with the Jackknife and walking away, losing voluntarily via count-out. The idea is that Nash cares more about teaching his friend a lesson than beating him, but it’s very rich of WCW to exploit Hall’s addiction and present a purportedly moving scene at the same time.

Halloween Havoc is a disaster.

In an even worse match than the Road Wild main event, Hogan beats the recently signed Warrior. In the ultimate stanza of poetry, a terrible, supernatural-leaning storyline quite literally blows up in Hogan’s face when he burns himself with the fireball he was meant to aim at his opponent. This follows some of the most wretched, phoney action ever presented in a marquee match. Hogan, cool by association for a couple of years, is now back on 1995 form.

There’s one very strong match at Halloween Havoc ‘98: Goldberg’s successful defence of the title in the main event. He goes over DDP, who gets over as a ring general for guiding Bill through it. Unfortunately for WCW, approximately 25% of the paying audience don’t see it, since several systems providing the feed cut it off early when the show runs too long.

An enforced replay of the main event on the following Nitro actually breaks the all-time cable wrestling ratings record, but it’s nothing more than a spectacular consolation goal.

January 4, 1999 - Finger Poke Of Doom

It is reported in the December 21, ‘98 WON that, on December 14, a frazzled Eric Bischoff held a talent meeting to announce that Nash and DDP had joined the booking team. On December 27, at Starrcade, Kevin Nash is booked to end Goldberg’s lengthy undefeated winning streak and take the WCW title from him.

Nash, who offered his services, will later quip that he should have said “Let’s go to a strip club” as a means of helping a stressed Bischoff.

The match at Starrcade is remembered only for the fact that the booker beat the top star, and while that is certainly symptomatic of WCW's slow death, what's often lost is that Nash receives some support from the crowd. Goldberg is favoured, but the word "mixed" is not an inaccurate description of the atmosphere. There is, at least, interest left in the idea of Nash as a top babyface.

The World title rematch is set for January 4, 1999 at the Georgia Dome on Nitro. It doesn’t happen.

Instead, what happens to Steve Austin a lot happens to Goldberg, because that’s what’s in: Goldberg is arrested. Nash instead puts up the title against Hogan, magically back from a November “retirement” few took seriously.

Hogan prods Nash in the chest with his finger - the “Finger Poke of Doom”. Nash bumps theatrically to the mat, willingly takes the pin, and magically pops back up, celebrating with Hogan and a reformed nWo also featuring Luger, Hall, and Steiner. The histrionics are funny, granted.

The scene is meant to provoke outrage - damn these disruptors, and their lack of respect for the belt! - but fans are over being jaded.

Usually, when you laugh in someone’s face, it’s because you’ve outsmarted them with a fiendishly clever idea. Reforming the nWo is not a fiendishly clever idea. It is an idea that convinces fans, who get worked into it for a few weeks, that WCW is out of ideas.

After initial interest in the reboot, WCW’s audience craters over the coming months. WCW will never again win a ratings battle. WCW, in just over two years, will be dead forever.

August 16, 1999 - There Is No End

There is no definitive end to the original nWo story in WCW, and it’s very fitting. Bischoff didn’t know how to do that, when the nWo Nitro concept bombed, and so it was essentially ended on his behalf.

Wearing the cooler red and black aesthetic, the ‘New World Order Elite’ is the name, and the unit quickly procures every piece of heavyweight singles gold.

If ‘Elite’ is subtext for “there will be no extraneous members this time”, it’s another con: Disco Inferno is part of the stable. Even though they’re ‘Elite’, they decide to “trim the fat” by jettisoning members within weeks.

The stable ends quietly when three key members succumb to injury - after which there is a slow, collective realisation within WCW that the whole thing is dead. Hall is ruled out until November when a car backs up over his foot in February. Luger suffers a torn bicep that same month. Hogan is shelved for three months when he gets injured at Spring Stampede on April 11. As ever with Hogan, the veracity is questioned. He’s back as a babyface in the red and yellow by August.

The date on this timeline reads August 16, 1999.

As the Elite dominate WCW for all of two months, the remnants of the old nWo, the guys who joined because WCW thought a t-shirt would get them over, are still just hanging around. It’s strange. It’s as if nobody has bothered to tell the likes of Stevie Ray and Horace Hogan that the nWo has been liquidated. Still wearing the original black and white tees, they are explicitly referred to as the ‘B-Team’. On August 16, 1999, Brian Adams is kicked out of a version of the nWo that doesn’t really exist. That’s as good a date as any to declare a time of death. An alternative date?

September 10, 1999, on which Bischoff is sacked.

December 20, 1999 - New World Order 2000

Under the creative direction of former WWF head booker Vince Russo, the nWo is rebooted on Nitro when the key champions - Bret Hart (World), Jeff Jarrett (United States) and Kevin Nash and Scott Hall (World Tag Team) band together to take over, again. The nWo rehash happens because WCW is torpedoing in popularity. Every business metric is plummeting. Rapidly.

The product is an incomprehensible mess, a weirdly meta broken TV show about a broken TV show.

The difference this time around is that the group wears black and silver colours, and goes by the guaranteed suffix failure of nWo 2000. Was it really going to be any good?

Message board pipe dreamers and Russo apologists mourn the potential of a group that is doomed instantly. ‘Instantly’ is not even the correct word; the group is untenable before its formation.

Hall gets injured in December, and can’t be in nWo 2000 before the year 2000 actually happens.

Unbeknownst to Hart himself, he gets concussed at Starrcade before nWo 2000 even forms, and must retire shortly thereafter.

In December, key protagonist Goldberg severs an artery and is out for months when WCW fails to gimmick the limousine window he smashes with his forearm.

The group, again, quickly and quietly fades away.

It’s somewhat safe to say that, as a Russo project - a Russo project in WCW, for that matter - nWo 2000 probably doesn’t succeed nor last regardless.

March 17, 2022 - WrestleMania X8

There is at least a decent narrative reason for this latest nWo retread, which happens this time in the WWF. Vince McMahon is able to do this because he purchased WCW and its intellectual property in March 2001, long after WCW self-imploded in bleak, but also darkly hilarious, fashion.

Vince brings in the nWo because in storylines, his ownership of the WWF is under threat. Nobody else is going to kill his creation but him. The original three - Hogan, Nash, and Hall - are playing it meta, performing as toxic locker room sh*t disturbers who will, presumably, drain interest in the promotion with their self-serving antics.

Again, the nWo does not work. The problems are both familiar and unexpected. Hall, sadly, is in no condition to perform. He had re-debuted on February 17; he’s gone on May 6 because he can’t conduct himself professionally.

Nash, clever enough to sit on his guaranteed WCW money and confident in the WWF’s ability to bungle the 2001 WCW Invasion angle, necessitating his star power in 2002, suffers a bicep injury in March.

At WrestleMania X8, in one of the loudest and most epic moments in wrestling history, the fans no-sell Hollywood and embrace Hulk Hogan - even at the expense of the Rock. Deep down, they’ve missed him, and they show him that by affording him a hero’s welcome. The difference between the WCW and WWF audience is stark. There’s no Horsemen guy in Toronto. The nWo isn’t going to work.

The original version of the nWo disbands that very night. Another ghostly version of the Order, with no real aim nor purpose, haunts the WWF over the next few months. It’s a vehicle for comedy - Goldust’s attempts to get initiated are played for laughs - and a generic, sad heel threat elsewhere.

On July 15, in a note of irony and some lovely foreshadowing, Vince officially declares the group dead on the same night he introduces its original mastermind, Eric Bischoff, as the General Manager of Raw.

The nWo, however, is not exactly dead.

29 years after the nWo was originally formed, the second iteration of the Bullet Club Elite - itself a derivation of the nWo - is still trying to “take over” at time of writing.

The nWo really is ‘4 Life’.